My grandma Phyllis described in a letter the heartbreaking moment when she and the family dropped my grandpa Gene off at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. They wandered the premises for about two hours, watching some recruits do target practice and hoping they might catch a glimpse of Gene.

“When we got back to the car frozen stiff your mom said, ‘I don’t want to stay here any longer and I don’t want to go either.’ I guess that was the way we all felt, Darling.” About 60 miles away from the Smiths’ home in Fort Atkinson, the family picked up a hitchhiking solider from Ohio who was headed north. Gene’s dad Frank insisted on bringing the boy home and feeding him lunch. “It was an awfully funny feeling having him there, Darling, just after you had left. I don’t know whether it made things better or worse.” That evening Frank drove the soldier to a local diner and made sure he got a ride heading in the right direction.[1]

Meanwhile, Private Smith was trying to adjust to Army life. His first few days were packed with a series of physical and mental exams, filling out forms, getting a uniform and his first regulation “high and tight” haircut, receiving inoculations, and shipping home any last vestiges of his civilian life. On Day 2, the recruits had a compulsory meeting called “The Articles of War” where they learned how the chain of command works in a wartime military. Gene described this meeting to Phyllis as the one where “the law is laid down.” Mornings started at 5:45, and by 6 am the recruits were expected to have gotten out of bed, dressed, washed, shaved, brushed their teeth, made their bunk, and reported to roll call. But as Gene explained to Phyllis in one of his letters, “Don’t take it too serious tho Darling because none of us new fellows have been able to do it yet. Lucky me, I can shave in the evening and it looks just as good in the morning.”[2]

At the end of the week at Fort Sheridan, Gene and 102 other fresh recruits donned their new uniforms, packed their bags, and were marched to the station to board a southbound train. After connections in Chicago and St. Louis and a sleepless night (there were no sleeping compartments), the boys found themselves staring out the train windows at a bleak Missouri landscape. “The hardest part of the trip was that I couldn’t keep my mind off you for even five minutes. Lonesomeness for you is something I just can’t knock down, Darling.”[3]

Arriving at Camp Crowder in Neosho, Missouri, Gene and his fellow recruits began the four-week basic training program (“boot camp”). It took him a while to acclimate to the Army rhythms and terminology. As he explained to Phyllis,

“If you get a chance to study up on anything pertaining to Army organization it probably will make my letters much more understandable because I haven’t the time to explain everything. And it’s impossible to be here and write to you without using Army terms. ‘Army’ is the only thing I’ve seen, heard, felt or any other sense for over a week now. (Except my lonesomeness for you, and most of the time I’m so busy jumping to someone’s orders that I don’t even have time for that.) Darling, it’s impossible to put into words the difference between this and civilian life. I feel as if I’m a different person in a different world. And I’ll be glad when I can get back to the other one. You’re there, Darling.”[4]

One of the Army acronyms that Gene learned on day one was “KP” – kitchen patrol. He and a few other recruits were singled out to work in the kitchens that first night. On another day his first week he got in trouble for not having his shoes lined up precisely 3 inches from his bunk at morning inspection. More KP. And the training was physically grueling. The men were run through obstacle courses, sent on long hikes in the surrounding countryside with heavy packs, and marched around camp in formation. Then there were the various instructional periods in classrooms or outside with rifles. The days felt endless, and on top of this Gene had caught what the recruits called the “Crowder croup” – a cough that wouldn’t let up.

“It seems that all the fellows have it. It’s a terrible deep cough and you’re spitting up slugs all the time. My nose has been running continually since yesterday morning. You should be in a large classroom or one of these instruction movies where there are three to five hundred fellows in a room. You can’t hear anything for the coughing on all sides of you.”[5]

But basic training wasn’t a completely terrible experience for Gene. He was starting to get a sense of who he was, what he was made of:

“Here men are men, Darling, in an undiluted form. They cuss and talk just exactly as they feel. Here you see fellows as they really are because many things are so darn trying and there’s no backing out, flinching or backtalk of any sort, and it sure shows up the guys in their natural color. In analyzing my own emotions and actions here and comparing them (to myself) with the other fellows I’m quite surprised. I’m an entirely different person than I thought I was. I didn’t realize I’m quiet and so darn conservative, Darling. That was the most surprising thing.”[6]

When Gene finished basic training on April 17th, he would have a choice: apply for Officer Candidate School or receive more technical training. He knew that the former would be the pathway to higher ranks as a commissioned officer, but Gene was thinking further ahead, particularly of a future career in communications. “Which would do me the most good?” he asked Phyllis in one of his letters. We don’t know how she replied to that question, but ultimately Gene decided to follow his heart and pursue advanced technical training.

Camp Crowder, it turns out, was an ideal place to do that. Although originally intended to be a joint training facility for the infantry and the Signal Corps, by 1942 Camp Crowder was exclusively a Signal Corps training replacement center[7]. Crowder offered a number of specialty courses and programs after boot camp. Gene sat the test for the radio corps and did well (40 of 50 questions right) but was assigned to the telephone corps. Initially, he was disappointed but then found out that only two in his squadron of 103 recruits got into the radio corps. Over 90 of the recruits did not get into either – they were classified as truck drivers, messengers, and other auxiliary staff.

Gene’s days were a combination of drilling and schooling, and by all accounts he excelled. He was promoted to corporal after only a few weeks at Crowder. Here is a typical day as described to his parents in a letter:

“Up out of bed at nine o’clock. Breakfast at 9:45. Infantry drill from 10:45 to 11:45. Then if we don’t have any extra duty we are free until 2:45 when we eat dinner. At 3:45 we go to school. In school we have classes for 50 minutes and then a 10 minute break for a smoke or anything we want to do. [This repeats] until 8:00 when we come back here for supper. At 9:00 we are back in school and we get out again at midnight. The lights in the barracks go out at one o’clock and here in the dayroom they are on until two so we can write. But usually a guy is so darn tired that he doesn’t care to write at all.”[8]

After a few weeks, Gene’s schedule would shift back to days (i.e., up at 5 am, stand in formation for reveille at 5:15, breakfast at 6, in class by 7…), and it would alternate every other pay period. In total, the instructional period for the telephone corps was supposed to be 26 weeks but Gene was able to skip the first four. Sometimes after classes were done for the day, Gene and his group were sent out on “night maneuvers”, simulating telephone carrier duties in the field. They learned how to set up and troubleshoot switchboards in all manner of terrain and weather conditions.

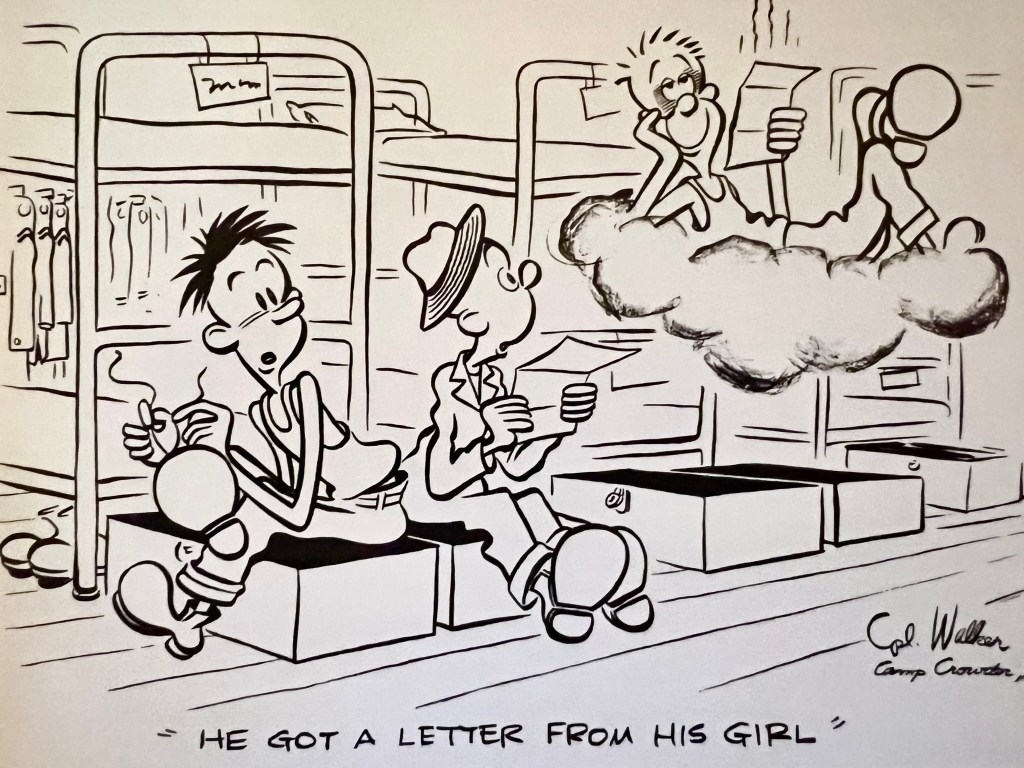

April and May of 1943 were particularly rainy. One of the barracks got flooded, and a young soldier by the name of Mort Walker made light of the dismal situation through a series of humorous drawings. Walker’s experiences at Crowder inspired “Camp Swampy”, the setting of a comic strip he published for decades – Beetle Bailey.[9]

Gene’s major solace were the letters he received from the family back home and especially Phyllis. The two of them shared moment-by-moment accounts of their days and endlessly planned how they might be able to meet up in person. In May, Phyllis managed to secure a break from her duties at St. Mary’s Hospital and arranged a visit to Missouri, arriving by train on May 23rd. She stayed at a boardinghouse in Neosho and met up with Gene as much as his schedule would allow. They went out on dates and had a picnic one day, enjoying each other’s company and talking about how their future might unfold. Gene suggested that they get married right then and there, and Phyllis agreed. In a rush of excitement, they called Phyllis’s parents to get their permission. To their surprise, Al and Jessie Reiner did not like the idea. They told Phyllis to come home, and dutifully, on June 2nd she did.

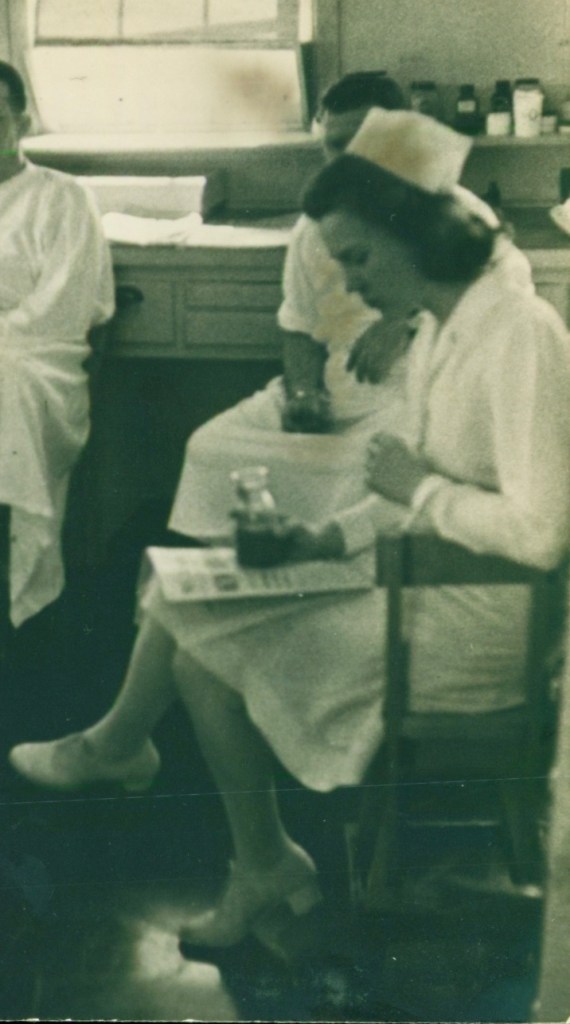

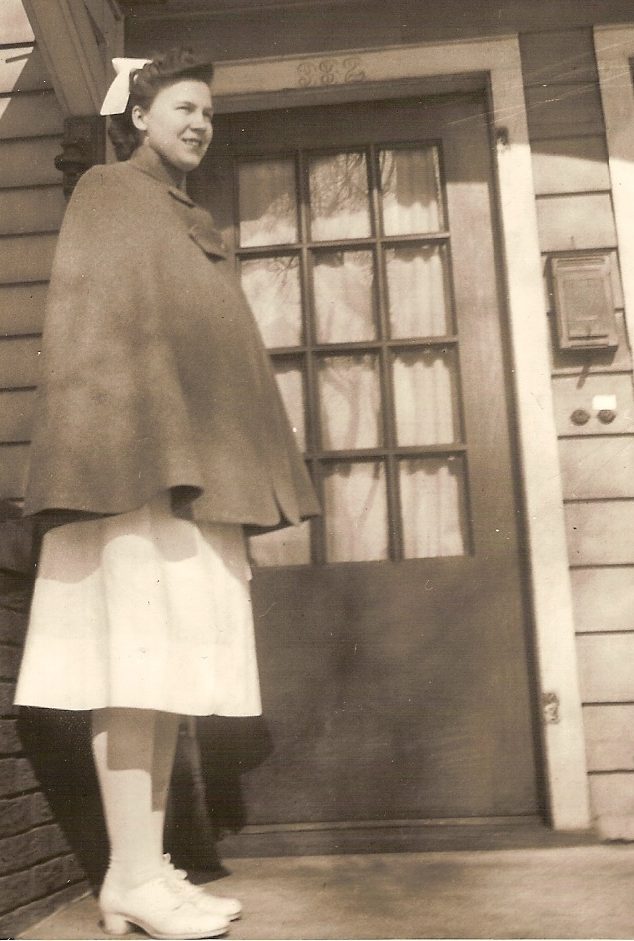

Back in Madison that summer, Phyllis came down with a serious respiratory illness. She worried that her tuberculosis had returned. She was attended by two different doctors at St. Mary’s who gave her conflicting opinions about what looked like a spot on her lung in an X-ray. Meanwhile, she was feeling conflicted about her future. In a letter dated July 16th, 1943, Phyllis wrote to Gene: “If I am perfectly alright, I don’t know whether I should continue nursing or whether I should go to Missouri and be my Darling’s wife. What is best to do, Darling?” After a couple of weeks in the hospital, Phyllis received the “all clear” from her doctors, and she decided she would quit school and join Gene in Missouri. When she went to turn in her books, one the sisters at St. Mary’s talked her out of it. She wrote Gene on July 21st, telling him she’d be going back to school on August 4th. And then, to everyone’s surprise, Phyllis showed up on Gene’s doorstep on July 23rd.

The couple arranged to get married at Camp Crowder’s chapel on Saturday, August 7th. But there was a hitch in that plan: when Phyllis went into town to apply for a marriage license on Thursday, August 5th, she was informed that a new law had gone into effect requiring the applicant to wait three days to receive the license. Three days meant Sunday, and the court offices would be closed, but the recorder of deeds told Phyllis to call his home on Sunday morning and he’d fetch the license for them from his office. He said he’d be home all day. So, they rearranged their plans to marry at the chapel on Sunday at 2:30 pm, and at 11 am that day, after getting herself dressed and ready, Phyllis phoned the recorder’s home. The person who answered said that the recorder had left to visit his son in the countryside, that he had waited until about 10 am but figured they weren’t coming. Phyllis was distraught. She called the recorder’s son’s home, but the recorder hadn’t arrived there yet. She tried to call Gene who was still at camp but was told there was no Eugene R. Smith there, only a Eugene F. Smith. In a frenzy, she hopped on a bus to camp, found Gene, and they tried to phone the recorder again at his son’s house. This time they got him. The recorder told them to go to the Justice of the Peace, who would be able to open the recorder’s office and get the license. They raced to the Justice’s office, but he had left five minutes earlier and couldn’t be found. They had to call off the 2:30 pm wedding. Gene and Phyllis didn’t catch up with the Justice until 7 o’clock that evening.

Gene and Phyl’s plans for a picture-perfect wedding were dashed, but after hours of scrambling they finally had the marriage license in hand. Their best man and bridesmaid had gamely stuck it out with them through a frantic afternoon, and the best man was due to ship out any day. So they thought, why wait? They asked the Justice to marry them on the spot, which he did. As Gene described it in a letter home, “It was the most exciting, most disgusting, most wonderful day I’ve ever lived.”

As a married couple, Gene and Phyllis were entitled to live off base. They moved into a simple little cabin a few blocks from the Camp Crowder gate, and Gene had to get up at 3:30 am to catch the bus into camp to be on time for reveille at 5 am. Phyllis got a part-time job as a waitress, and by the end of August she had found a position as a dental assistant at Crowder. The newlyweds spent as much time together as their schedules would allow. Typically, Gene would come back to the cabin by 8:30 pm, but on at least one occasion he was stationed “on bivouac” at his school building, operating a repeater terminal[10] and sleeping on the floor. He typed one of his letters home to his parents on a teletype machine while camped out at school.

On October 26th, Gene took his final exam and concluded his schooling at Crowder. He got his report card on the 29th and within minutes received his “shipping orders”: the next day he and three others from his group would join the 3110th Signal Service battalion, Company C. But what exactly that meant was not yet clear. In the short term, he was assigned to a detail at Crowder and would need to sleep on base except on nights he had express permission to leave. Gene suspected his group would be sent elsewhere for field training but when and where that would be he could only guess. He and Phyllis managed to obtain a two-day furlough in November, making a quick visit to the Smiths in Fort Atkinson. Then it was back to work in Missouri and back to waiting for news.

That news finally came in mid-December – Gene was heading out, destination unknown. Within a few days, the couple packed up their little home in Neosho, Phyllis gave notice at the dental office, and they celebrated an early Christmas, knowing that they would likely not see each other on the day. Phyllis traveled home to Wisconsin, while Gene boarded a troop train. His train took an intentionally roundabout path, and the men were forbidden from sending messages en route, which could disclose information about the large troop movement. Once settled, Gene called Phyllis and told her his exact location: Camp Charles Wood in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The connection was poor and the two couldn’t hear each other, but Gene managed to communicate to Phyllis through the operator that he would have the New Year’s weekend off and that she should check the train schedules and come join him. She did just that, and on New Year’s Day the pair enjoyed sightseeing in New York City – about an hour and half away from Camp Wood by train. Gene reported to duty on Monday the 3rd and Phyllis took the long train trip home.

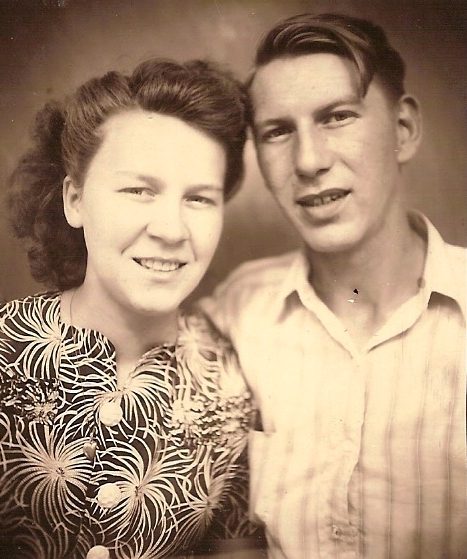

Two weeks later, Gene managed a brief visit to Wisconsin and back. He knew his team could be shipped out at any time, so he took this final opportunity to see Phyllis, his parents, and his sisters Shirley and Ruthie. I believe this photo may have been taken during that furlough:

Once Gene got back to New Jersey, his letters became more cryptic. He and his team were sent on assignments in the area, received tactical training using gas masks, and learned how to operate “Tommy” – the Thompson submachine gun. But Gene couldn’t disclose much, and starting on February 18th, his letters had to pass the censor before being mailed. He was at least able to tell Phyllis that he would be out of communication for a while, and not to worry about that.

It turns out that Gene and his team had left Camp Wood on February 14th, 1944 and stayed for six days at the point of embarkation, Camp Shanks, New York. Their unit and about 8,500 other soldiers[11] then took ferries to New York City and boarded the British vessel RMS Aquitania. On board, rumors circulated about where the ship was headed. As Gene later described in a letter, “We were pretty sure it was to Europe but you know how rumors are and there were very recent dates on the walls in pencil [listing] Pacific ports.” About two days before reaching their destination, the troops were told: they would be coming ashore in Britain.[12]

Cpl. Smith was about to get what he later called “a ringside seat” to the invasion of Europe.

* * *

To continue this story sequentially, you can read about Gene’s wartime service in England during the spring and early summer of 1944.

To go back and read about the events leading up to Gene’s enlistment, you can follow this link.

[1] Letter from Phyllis to Gene dated March 25, 1943.

[2] The details from Gene’s letters home closely match the Army’s own description of what new recruits could expect, as seen in this War Department training film from 1944: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85g4BKgrh0E.

[3] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated March 21, 1943.

[4] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated March 25, 1943.

[5] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated April 2, 1943.

[6] Ibid

[7] Amick, Jeremy P. 2019. Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.

[8] Letter from Gene to Vina and Frank Smith dated April 23, 1943.

[9] See pp. 52-53 in Jeremy P. Amick’s (2019) Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.

[10] In a letter to his mother-in-law Jessie Reiner dated October 26, 1943, Gene explained that “there are two general types of apparatus, carrier equipment and repeater equipment. The carrier is a sort of small radio transmitting station. Its purpose is to combine telephone conversations to high frequency electric currents and send a number of these combinations over one telephone line thereby reducing the cost of material, installation and maintenance of lines. They also have provisions for receiving and separating these frequencies and conversations. The repeaters are ‘step up’ stations, so to speak between the carrier terminals. They do much the same job as a pumping station in a city water system. It’s just a matter of increasing the pressure so it will carry to the place where it is to be used.”

For more insight into how these teams operated in the field, these Signal Corps training films are helpful: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kz-yytNbOyc and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LACLE6YTV28.

[11] Leonard Cizewski’s website chronicling his father’s wartime service reports that the number on board may have been closer to 12,000 (http://www.ibiblio.org/cizewski/felixa/deployment/unit.html).

[12] Gene was able to relay these details to Phyllis once the War had ended in Europe – specifically, in his letter dated May 21, 1945.

Leave a comment