The colonization of North America is so relatively recent that our notions of what’s “old” and “worth preserving” are a little different from those of our European counterparts. Similarly, a fascination with family history, while not unique to Americans, takes on an oddly obsessive quality among some in the U.S. (ahem…. guilty as charged).

Any time we attempt to reconstruct the past, there is a tendency to gloss over certain details and emphasize others — often through the lens of present-day values and systems of power. There’s also an urge to present “facts” when what we really have are hunches. Does our relatively short collective memory in (non-Indigenous) America make us more vulnerable to these distortions? I wonder. (If you have thoughts on the subject, please post a comment below!)

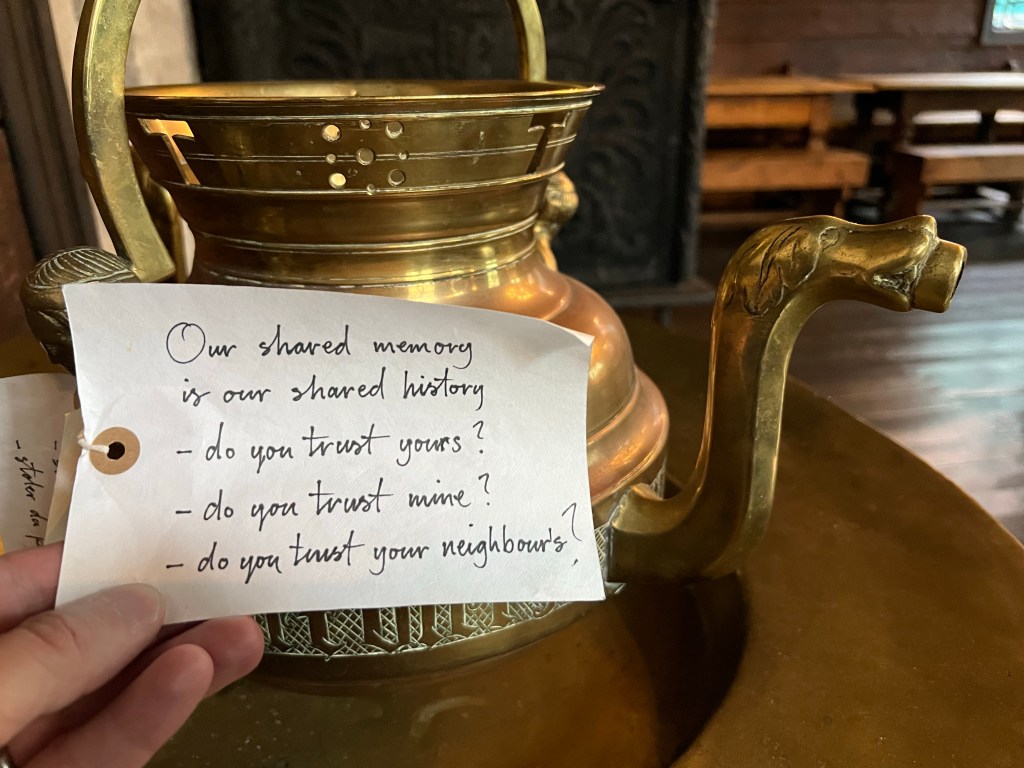

I started my day yesterday in Bergen, where I visited the Hanseatic Museum’s “Schøtstuene” (assembly rooms used by the German Hanseatic merchants who had established themselves in Bergen by the 1240s). One thing that I loved about the exhibit was how the curators presented ambiguities in the historical record. The exhibit took great pains to distinguish originals from copies from reconstructions (and all flavors in between). But they often admitted that they didn’t know. And the curators posed as many questions as they provided answers.

This playing with the admixture of originals and reconstructions is taken to a whole other level at the Gamle Bergen Museum — a collection of old homes and businesses from all over Bergen that have been reassembled into an open-air museum. Actors in 19th century dress sit patiently in opulent sitting rooms, waiting for you to arrive so that they can recount the day’s events. As a former resident of Williamsburg, Virginia, where I was sometimes chatted up by 17th century “re-enactors”, you’d think I’d be prepared for this sort of thing, but I never am.

Leave a reply to Jesse Rude Cancel reply