On the morning February 28th, 1944, Cpl. Eugene Smith woke aboard the RMS Aquitania. He had heard the ship’s anti-aircraft guns fire a couple of times during the night but the word that morning was that it had just been a test. He and the rest of Company C took their turn in one of the aging ship’s grand diningrooms for the first of their two daily meals: watery oatmeal (again). After chow, Gene and a few of the guys headed up to deck for a smoke break, just in time to catch a glimpse of the northern coast of Ireland. A year ago he had been just a farm kid who had scarcely left the state of Wisconsin. Now he was Cpl. Smith and on his way to the European theater of the War.

After navigating the Firth of Clyde, the Aquitania docked at Greenock, Scotland. “I can still close my eyes and see the wonderful sight,” wrote Gene to his wife Phyllis back home. “The harbor was full of boats of all sizes, descriptions, colors and nations. It gave a fellow a sense of security with the battleships. And too there were planes flying overhead almost all the time. They were English ‘Spitfires’.”[1] Gene and his company stayed on board until the evening of the next day, disembarking shortly after dinner. “What a funny sensation,” wrote Gene in that same letter, “to put your feet on solid ground again!” Ironically, he felt seasick only after putting ashore. The men were directed to an overnight train which took them south to the town of Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk (East Anglia). The train was so crowded the men had little choice but to stay awake all night. They played cards to pass the time as the train rumbled south past Glasgow and the Scottish countryside.

At about nine or ten the next morning, the troops arrived into Bury St. Edmunds. From the station, the men were marched for about a mile towards the camp, each carrying roughly his own body weight in packs on their backs.

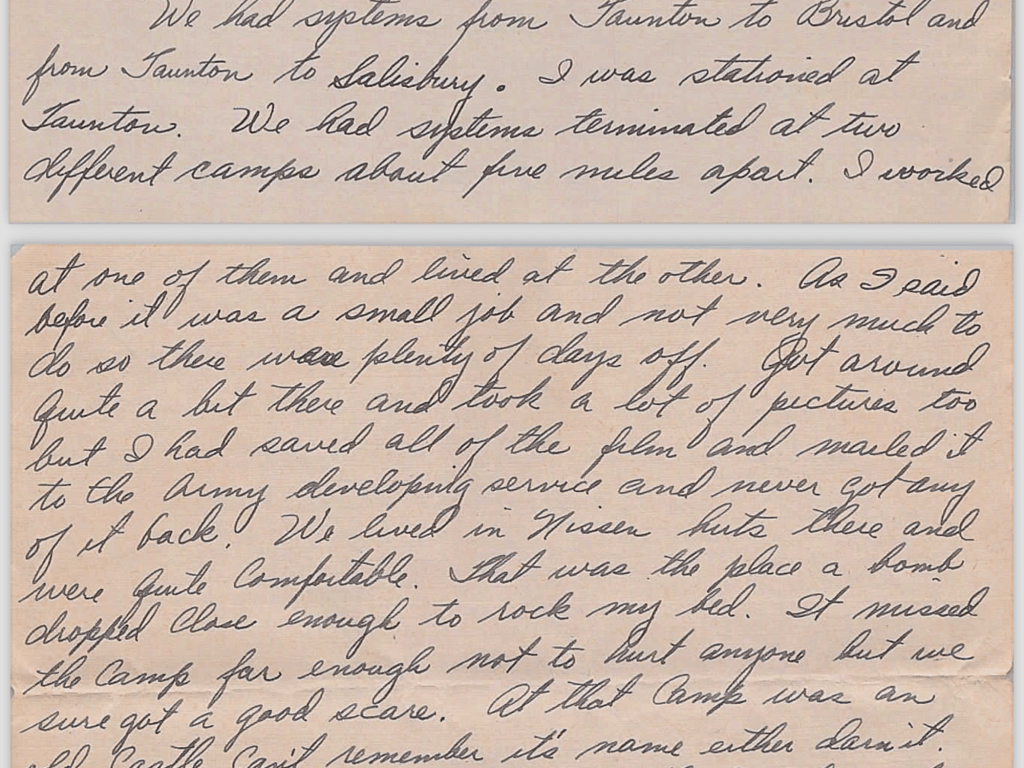

“It was all uphill but the thought of a bed and some comfort ahead kept us going. What a disappointment! It was in the middle of the winter and there were a bunch of tents staring us in the face. No heat, no light, muddy floors, no nothing but a tent and a bare Army cot. We had only one blanket – no two, but it still wasn’t nearly enough. We slept with our clothes on and shivered.”[2]

Conditions at the makeshift camp eventually improved after a few weeks, but Gene’s letter described great stretches of doing nothing interspersed with marching, training, and “detail” (i.e., grunt work). And amid what Gene felt was a “pointless, disgusting life”, there were also episodes of terror. The camp at Bury St. Edmunds was situated near a British airfield, and the men were often awakened by air raid sirens when the Germans bombed the area.

Gene described what that was like: “First a screeching siren went off that was enough alone to shatter a person’s nerves. Then all would be deathly quiet, and then another siren, and then you’d hear planes coming closer and the anti-aircraft getting louder and louder […]. Finally the planes [would be] going over with me lying on my cot shivering and praying for all I was worth.” No bombs fell on Gene’s camp, but he reported hearing many explode in the vicinity, and he “learned to identify German planes by ear as easy as an Englishman.”

After about two months in Bury St. Edmunds, the men were sent south to Burton Bradstock on the Dorset coast. Gene’s team camped out on a hill overlooking the valley and the little town. They were only there about a week, awaiting orders for their next assignment, but they welcomed the warmer coastal weather. Those orders came around April 15th, and they were moved to Bampton in Devon, which Gene described as “a one horse town back in the middle of nowheres”. In Bampton, the men were billeted on the second floor of a Methodist church, which turned out to be a less than ideal arrangement:

“Well I do remember the Sunday the minister came up and gave us hell because there was so much noise and cussing going on that it disturbed his ceremony. Another time one of the fellows saw a switch by the window and threw it to see what would happen; nothing did but in a short time someone came up and complained of not being able to use the pipe organ, and sure enough, throwing the switch fixed it.”

After only a week or so at Bampton, the men were reassigned to different work teams and sent out in small detachments. Gene and four or five other men were assigned to run a public address system for a network of American camps in the area, including in Plymouth, which was a port of embarkation on D-Day. As Gene explained in his letter, “It sure looked like a ringside seat to the invasion and we were pretty happy about it. We studied the equipment, set it up and took it down and experimented with it. Evenings we would take it around to different camps and play records over it or connect it up to a radio in our own camp.”

The men were stationed in a park about three or four miles from Plymouth. They stayed in tents without modern conveniences, but Gene was warm and didn’t mind the rough living. And fortunately, they had a fairly permissive commanding officer who would give them passes to town when asked.

“As a result, I spent quite a bit of time in Plymouth. It might have been a nice place before the war but there were places ten blocks square that were bombed flat to the ground. There was hardly a single block that didn’t show evidence of bombing. One of my favorite spots to hang out was the ‘Hoe’. It is a park built on a cliff overlooking the harbor which leads into the channel. It was a beautiful sight to look out on the water and see ships as far as the horizon, thousands of them.”

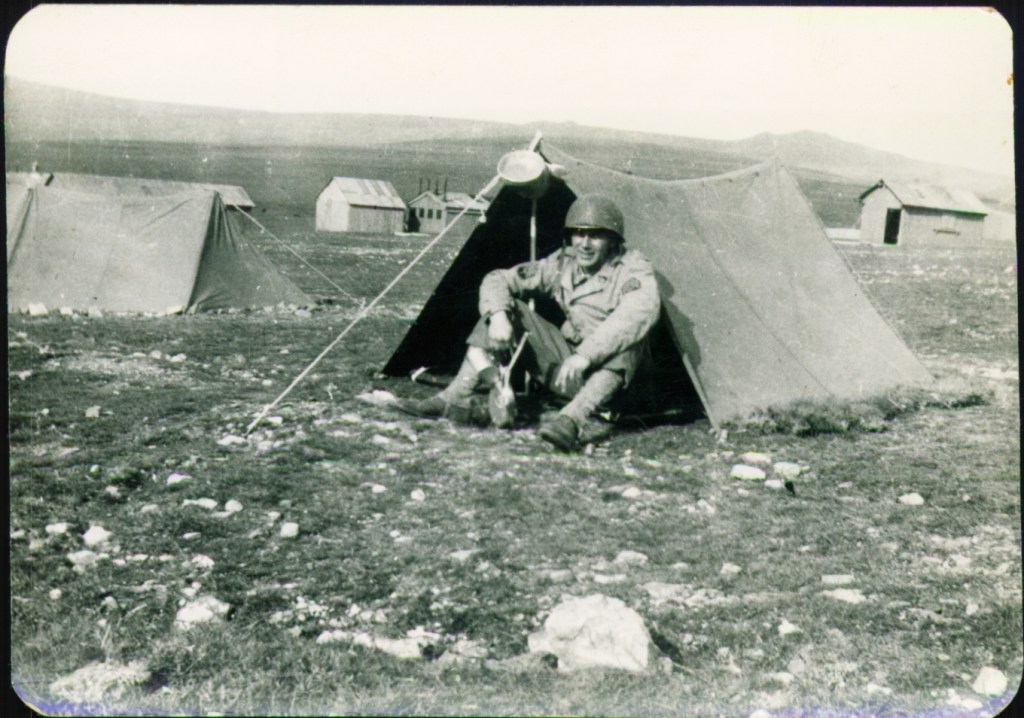

From late April until late June of 1944, Gene and his team were stationed near Taunton, where they set up communications systems between that town, Bristol, and Salisbury. They had systems terminating at two different camps about five miles apart; Gene worked at one of the camps and slept in a Nissen hut at the other. One night while he was there, a bomb fell close enough to the camp to rock Gene’s bed. But generally, those days in Taunton were easy going.

After this point, “things happened faster,” according to Gene. Around June 25th, Gene and his team were sent to a camp at Bridestowe, just north of Plymouth, where units were brought in for processing before shipping across the Channel. After a couple monotonous days of drilling and classes, Gene and three other men were offered a temporary job running carrier and repeater systems near London. They leapt at the opportunity to get away from Bridestowe and headed to the job site – an airfield at Windsor.[3] Gene and his three companions ran a repeater station from a tent in the woods near the base. This set-up enabled communications between London and the airfield, and then to France via radio. The guys were there about a week before heading back to Bridestowe, but before they left Gene and one of his friends had an unfortunate encounter.

The men had been taking it in turns at the repeater station; one or two worked the station while the others could go into town for food, etc. One evening when Gene and his buddy “Newk” (Arvon Newkirk) were in town, they had a few beers at a pub and were making their way back to their truck when they passed a dance hall that was letting out for the night. Twenty or so African American soldiers were coming out of the hall; they saw Gene and Newk and, according to Gene, demanded to know why they were there. In Gene’s recollection, the men were drunk and angry that two white soldiers dared to be in town that night. Just as U.S. Army regiments were strictly segregated in those days, American commanders had designated particular evenings in town as “for whites only” or “for coloreds only”. Gene and Newk were in town on the wrong night.

The situation escalated quickly. More African American soldiers arrived until there were over a hundred men in the street, according to Gene.

“So, Honey, right then for the first time in my life I found out what ‘mob spirit’ meant and I was on the short end of it. Newk and I did what little we could to defend ourselves but we didn’t have a chance. If we turned our faces one way we were hit on the other. In practically nothing flat we were in the gutter with about three inches of water (it had just stopped raining). God or a guardian angel or something must surely have been watching over us right then because just as I got to my feet all hostilities ceased. Newk was still down. A couple of colored officers, bless their souls, had gotten in the center with us somehow and their bars [jacket insignia] did the trick. They walked with us the remaining block to our truck and we took off.”[4]

In his letter to Phyllis, Gene used this incident to explain his negative attitude towards African Americans. But I have to wonder what attitudes my grandpa brought with him that evening and whether the incident may have confirmed beliefs he already held. My grandpa was a product of his times (as we all are), and the decades leading up to and including the Second World War were an especially fraught period in American race relations. We only have my grandpa’s version of events that evening; there might be more to this story.*

Gene’s detachment returned to Bridestowe around July 5th and stayed there for the next two weeks. The company was then sent to a marshaling area near Southampton where they awaited transport to Normandy. They didn’t have to wait long. The Allies had managed to secure a toehold in France but needed Signal Corps teams to coordinate their actions. The time had come for the 3110th Signal Service Battalion to do their duty on the other side of the Channel.

***

This story will continue in another post that has not yet been drafted. Please stay tuned.

To revisit the first part of Gene’s military career, see this post.

***

[1] Letter to Phyllis dated May 21, 1945.

[2] Ibid.

[3] According to Leonard Cizewski’s website, a detachment of men were sent to an airbase in Middle Wallop. This might be the location Gene meant (instead of Windsor) because he describes the town of Winchester as being roughly 15 miles away.

[4] Letter to Phyllis dated May 29, 1945 (a continuation of a summary of his time overseas that Gene started in a letter the prior week).

* It’s tempting to gloss over episodes like this because they complicate or contradict a picture we have in our heads about our loved ones. Family histories are as susceptible (if not more susceptible) to selective memory as national histories are. Certainly, America’s “Greatest Generation” was self-sacrificing, a generation of men and women more capable of keeping the country’s individualistic impulses in check — at least compared to the generations that followed. But they were also raised in an environment where essentialist and supremacist notions of race, class, gender, and sexuality often went unquestioned. It’s easy to lionize or demonize this generation, depending on one’s agenda. But an honest attempt to understand history on history’s terms requires us to hold multiple (and sometimes contradictory) perspectives at the same time.

Leave a comment