When I was preparing for this trip to Norway, I posted on a Facebook page for the community of Arna that I was seeking some local history expertise. I had discovered that my great-great-great grandfather, Ole Jensen Hauge, emigrated from Arna, but I didn’t know anything about the area. Local volunteers kindly came to my aid and put me in touch with two people: Arne Storlid, a distant relation of mine, and Ole Johan Hauge, a local history expert. I had the great pleasure of meeting Ole Johan Hauge this morning, and then we went together to meet Arne Storlid. (I write about that meeting here.)

These days Ole Johan is a volunteer teacher at the Espeland Prison Camp Museum, the only preserved prison from Norway’s occupation era. Formerly, Ole Johan was the chairman of the museum’s foundation. The facility at Espeland was set up by the Nazis to incarcerate political prisoners, and it stands as a testament to the horrors inflicted during the occupation. Before he retired, Ole Johan worked around the world for over 25 years for the International Red Cross. His last call of duty was in North Korea, but he also helped direct the rescue operation after the tsunami disaster in Indonesia in 2005. Additionally, he worked in Sri Lanka, Bosnia during the war, in China, Myanmar, Lebanon and Malaysia.

Ole Johan Hauge’s family hails from one of the several Hauge farms clustered in Arna’s Langedalen Valley — not the one where my immigrant ancestor grew up but one close by. Still, it’s likely that he and I are distantly related.

A few weeks before my visit, I had asked Ole Johan if he would be willing to meet me for a coffee and tell me a little about the local history, particularly about the conditions in those years when locals like my ancestor Ole Jensen sailed for America. Ole Johan agreed, and then he went the extra mile: he actually wrote a local history of the Hauge farms and sent it to me. This act of generosity completely floored me. I have done my best to translate Ole Johan’s excellent history, and I’ve pasted it below, along with the photos and drawings he included. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

A HISTORY OF THE HAUGE FARMS OF THE ARNA VALLEY, written by Ole Johan Hauge

The Hauge farms in the 1800s

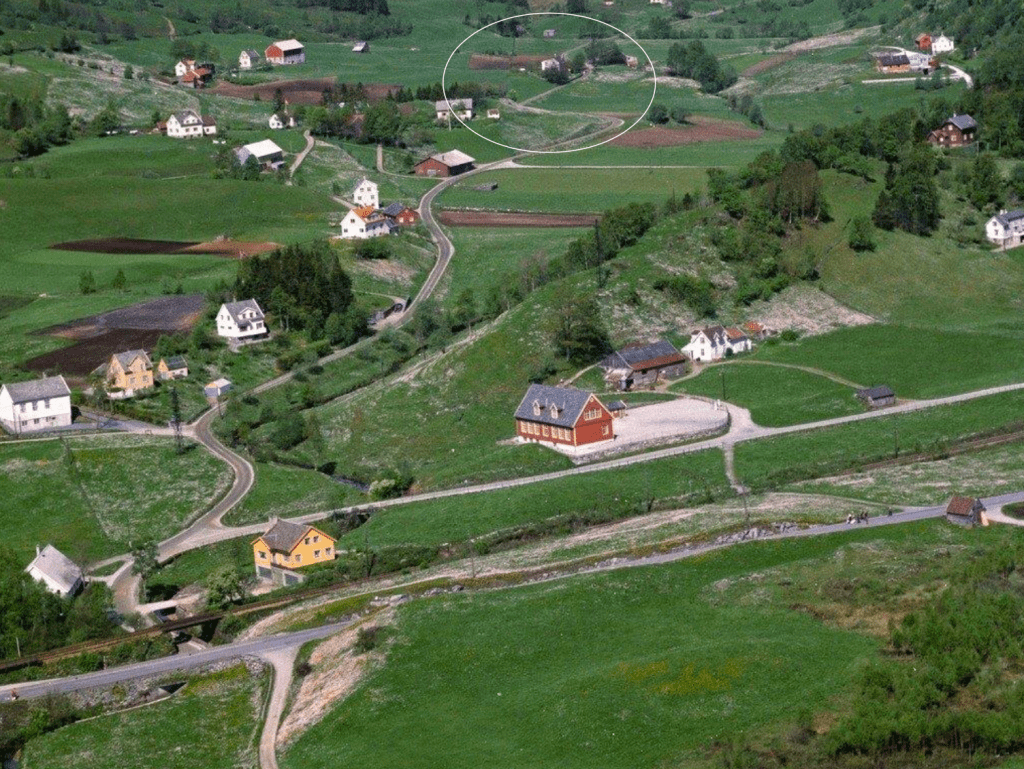

The green valley of our childhood, Langedalen, is located within the lovely Arna Valley and about 20 kilometers from the center of Bergen. Beautifully situated in this valley in one of the side valleys popularly called Oladalen are several Hauge farms (“Haugegårder”).

In the 19th century, Norway was a poor farming country with little contact with the rest of Europe. That was also the case in Arna. There were many small farms that could not feed many people. And there were many children in the families then, and only the eldest son (odelsgutt) could take over the farm. The rest of the children had to find work outside the village as there was little industry in the 1800s.

It was hard to do farm work in Vestland, steep slopes and and much heavy labor. Everyone on the farm had to pitch in, and from the time they were little the kids had to work too.

But when the children grew up, most of the children in a family had to make a choice. The oldest boy took over the farm, the girls were married off, and the rest of the sons had to find something to do outside the village. So they had to leave, and the closest place where many settled was Bergen. Or they went to other industrial towns in Vestland. And for some the dream was to come to America.

Dreaming of America

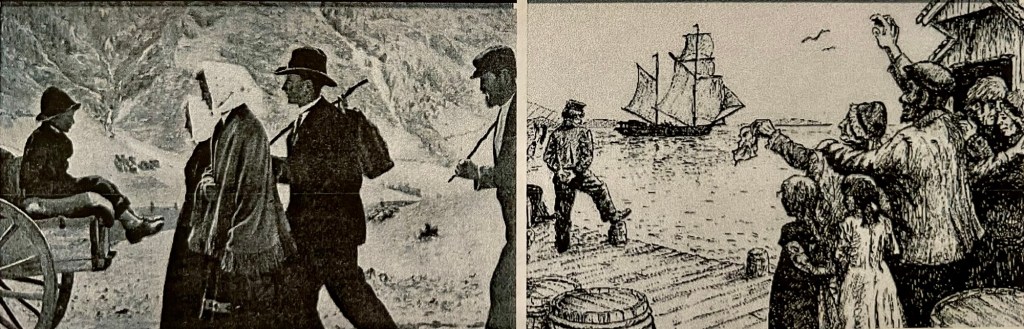

Early on, the youngest boys in the large families were dreaming of getting out and finding a place to live and work. For many, the dream of America, far away on the other side of the ocean, was just that — a dream. But some took the chance and set out.

It was tough to say farewell to home and everyone who lived there, but for many this was the only way out.

The voyage across the ocean was a long and tiring journey, and many were probably afraid of what awaited them in an unknown country.

Once in America it was a matter of finding a place they could settle down and work the land.

For many this was a tough existence, but most managed to build a life for themselves in that new land. They could never, however, forget those they left behind in Norway.

The community school (omgangsskolen)

At the beginning of the 19th century, there was no regular schooling for children who grew up in the countryside. Sometimes a “community teacher” (omgangslærer) would come to the village. He would live on one of the larger farms and the children would come to that farm. School was held in the main room on the farm, and the community teacher would be there for several weeks. Such community schools continued until the 1880s. Of course, they did not exist in the cities.

Here is a drawing depicting teaching in a so-called community school in the countryside of Norway at the beginning of the 19th century.

The photo shows children who were provided community schooling in the 19th century.

Borgaskaret, an important pathway

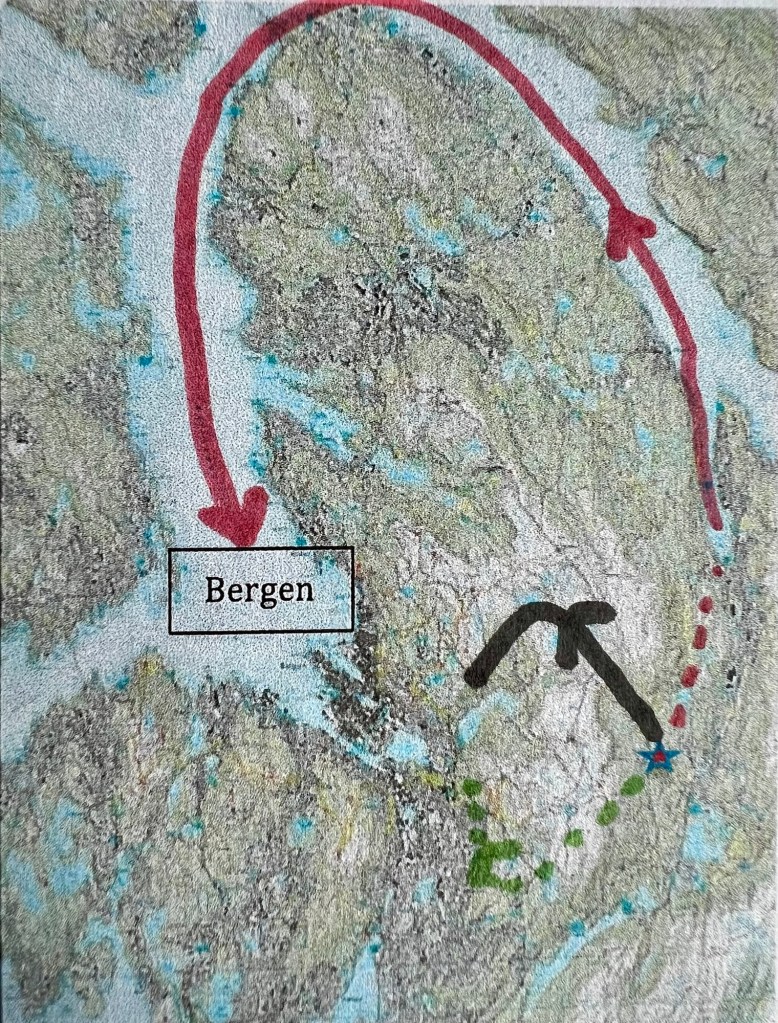

When the farmers of Hauge went to Bergen to sell or exchange their farm products, the trip over the mountain to Bergen was the shortest way. Then they had to go via the Borgaskaret Path over the mountain to the city.

Borgaskaret has been an important route to get from Langedalen and over Byfjellet to Bergen. This path was for hundreds of years the most common way to get to Bjørgvin town (the old name for Bergen) where the farmers of Langedalen could exchange important trade goods.

There was another path you could take if you wanted to go from Langedalen to Bergen, and that was the old postal road. It went over Natland and Kolstien, through Erdalen, over Bratland and then down through the slopes to Hauge. From there it went on over to Lone, Espeland and on to Arna and Garnes. But this road came much later when people started using carts and horses to transport goods. The trip via Borgeskaret was only for those who walked on foot and carried their goods on their backs.

Until the postal road was put into use, the path up Borgaskaret was the most commonly used. If there was something that needed to be traded, whether it was meat, potatoes or milk, you had to walk Borgaskaret with a load on your back, and it was an effort like no other. Those who have walked that path know that it is terribly steep up from Borge even without a huge load on your back. People from Fjellgården and Unneland also had to take this road when they were going to town. There is a place between Londalen and Hauge that is still called Odlandsskaret because the folks from Unneland used to come here walking over Neset and Lone via Odlandsskarert to Hauge and so on to Borgaskaret. Through the mountain pass, the path continued to the other side of the mountain and down to Tarlebø, past Svartediket and down to Kalfaret.

Settlement on Hauge in the Viking Age

The farm Hauge is located up in Langedalen, beautifully situated in the shelter of “Hauafjellet”. People have lived on Hauge since the early Middle Ages, but the land was used as far back as the early Viking Age.

There is a written record of farms and ownership from 1519, and at that time it was Sigmund on Hauge who was the owner. He was born in the 1450s and is the first of our ancestors whose name we know. Already in the Viking Age there were people who farmed in Langedalen. It was usually noble families in Bjørgvin who owned the land around the town, and they usually hired slaves or others to farm for them. In the beginning, no one lived where the land was; that happened when the land began to yield a return. Only later did people settle in the valley, but they did not own the land. The valley was at that time divided in two: the southern part went from Borge southwards all the way to Unneland, and the northern part went from Borge northwards. This is how Langedalen was divided for hundreds of years.

The entire Langedalen was under “Skjold Skipreide”. A skipreide was an administrative division of Norway into geographically delimited areas where the inhabitants were collectively responsible for building, maintaining, equipping and manning a leidang ship. The skipreides were not only located on the coast.

Exactly how old the skipreide division is is not known, but the skipreides originated together with the leidang system, and according to Snorri Sturlason, the laws were developed/improved under Håkon the Good and Sigurd Jarl in the mid-900s.

Towards the end of the 13th century, the skipreides became used only for fiscal purposes, and they remained the basis for tax administration until the 1660s. Skjold Skipreide was one of eleven skipreides in Nordhordland, which included large parts of the current Bergen municipality.

The first settlement on what is today Hauge was sometime in the late Viking Age. Two families, probably from Fana in Skjold Skipreide, are said to have come and settled in the valley where the Hauge farm is located. They settled there and built a house together – two families with a common living room but each one with its own space on the short sides of the house. Then they began to cultivate the land just below what we today call Byfjellet Mountain. It was quite common during that time to use slaves for the heavy farm work.

The first farmer on Hauge that we know anything about is Sigmund on Hauge who was born around 1450. Most of the church books before that time have been burned, and it is impossible to find previous owners. So it is likely that there have been landowning farmers on Hauge long before 1450.

The conflict between the Baglers and the Birkebeiners

We know that there were farms on Hauge and Borge when the conflict between the Birkebeiners and the Baglers* was at its worst in the 13th century. Many legends from this time still survive. One of these is related to the Hauge farm. The Baglers who lived in Bjørgvin had learned that the Birkebeiners were heading west to subdue the town. Afraid of being caught with their trousers down, the Baglers sent some soldiers up to Byfjellet to see if they could discover the Birkebeiners before they came over the mountain. One night with a full moon, they saw to their horror that hundreds of soldiers were lined up down on the Borge and Hauge farms. They ran down to the town where all the church bells were rung to warn the townspeople of the danger that was lurking.

But nothing happened, and the next evening the soldiers went up again and then down to Langedalen. Great was the surprise when they discovered that the “soldiers” were corn stalks – not Birkebeiners. But later the real soldiers did come and they defeated the Baglers down in Bjørgvin. This story has been told for generation after generation.

The “skaffers” on Hauge

The old postal route between Bergen and Christiania (Oslo) went via the Hauge farm, and in the 18th century the farm became part of the so-called skyss-stasjon system of the Norwegian government. This meant that the farm had to provide rested and healthy horses when someone came on public business. There were many such “skyss stations” or “skaffer farms” on the long route between Bergen and the capital, and this system worked excellently. Eventually, the farmers on Hauge were nicknamed “Skaffer” Lars, “Skaffer” Ola and so on. It was an honor to become a skaffer farm, which also meant that everything had to be in order. The horses were well-groomed and in order, and pretty much as the public demanded.

Throughout history, many officials came by postal road over the mountain and down to Hauge. There they changed horses before continuing their journey east. This was a service that meant a lot to the farms that were part of the skyss-station service, and the arrangement lasted for several hundred years.

A new era

Up until 1880, there was almost no development in Arna. There were mostly small farms and large families with children. Therefore, most of the youngest boys in the families left the village to find work. It was either to Bergen or to other places in Western Norway. Many also went over the sea to America. Young people from most families in Vestland went to America in the 19th century.

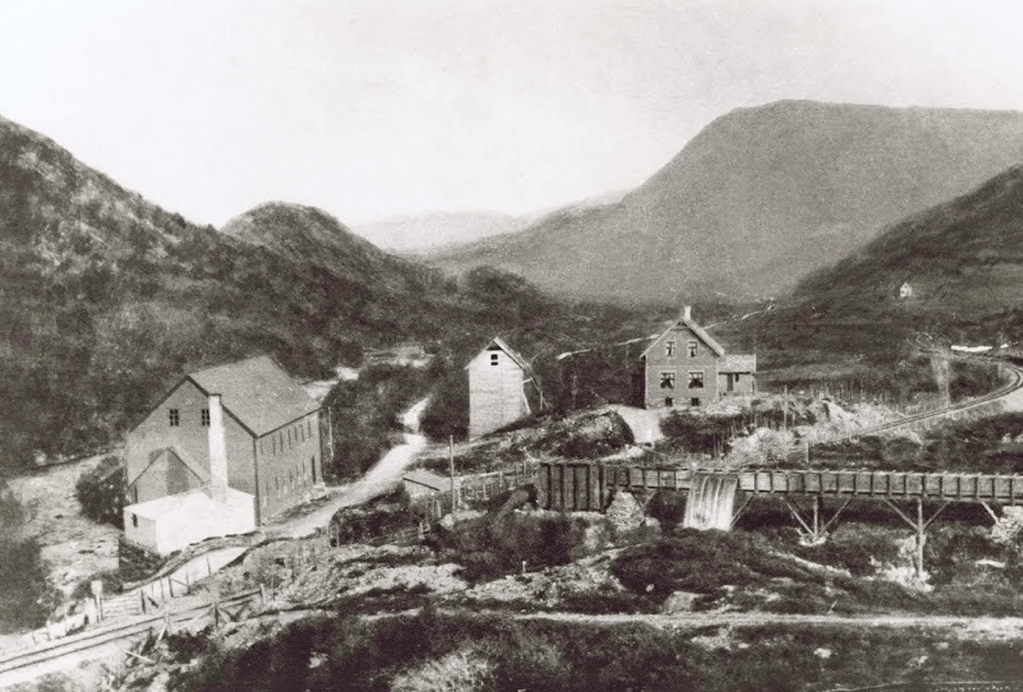

In 1885, something important happened for the development in the Arna Valley. The railway between Oslo and Voss was extended all the way to Bergen, and it was a great revolution for the development of Arna and Hauge. Thanks to the railway, several industrial leaders began to see the possibility of establishing industry in the village. There was plenty of electric power from the surrounding mountains, and in 1895 the Janus factory in Espeland was established.** This meant that the young people did not have to leave the village but could find a job near the farm.

Around the Janus factory, many homes were built for those who worked at the factory. In addition, there were shops and schoolhouses. This meant that those children in the family who could not live on the farms could find work at Janus, which many did. With the arrival of the railway, the road into Bergen was not so long, and many could have jobs in the city while living in Arna. After 1900, so much happened in the Arna Valley and it developed rapidly.

* A note from your translator: The Birkebeiners (Birkebeinerne) and Baglers were two rival factions in the Norwegian civil war era (1130-1240). They supported different contenders for the throne of Norway and controlled different regions of the country until the reign of Haakon IV, the king who is generally credited with reunifying the country.

** Janus produces woolen knitwear and is one of the oldest knitwear factories in Europe.

Leave a reply to Beverly Rude Cancel reply