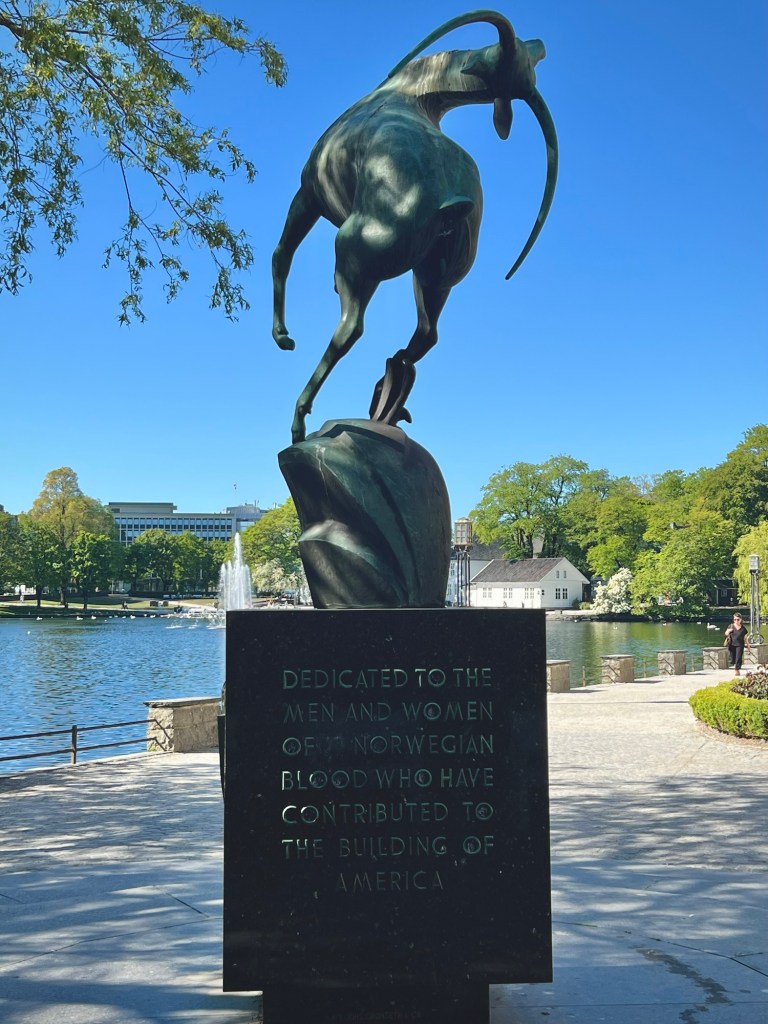

Two hundred years ago this year, a small ship set sail from Stavanger, Norway bound for New York City with 52 passengers and crew. This was Norway’s “Mayflower moment”.* Who could have guessed that over the coming century the number of migrants from Norway to the United States would reach nearly a million?

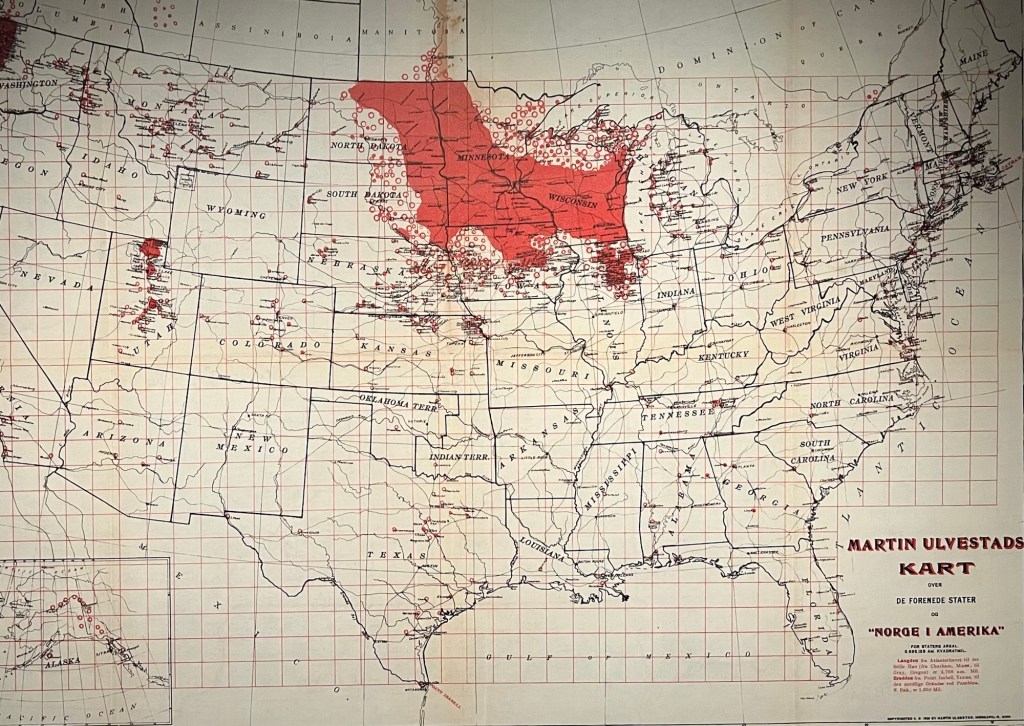

The Norwegian diaspora stretches far beyond the U.S., as Norwegian migrants have settled on every continent (see this link). But the American Midwest – particularly states like Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota and the Dakotas – became a kind of second homeland for hundreds of thousands of Norwegians. Those personal ties to Norway are increasingly distant today, as the immigrant generations fade from memory. But a handful of institutions in the Midwest are working hard to preserve this history and revive those ties (see especially Norway House and Sons of Norway in Minneapolis, MN, the Norwegian American Historical Association in St. Olaf, MN, Vesterheim in Decorah, IA, and the Norwegian-American Genealogical Center & Naeseth Library in Madison, WI).

My Uncle Phil and I visited one such institution, Livsreise, on January 23rd of this year. After walking our dogs through a park near Lake Koshkonong — on quite possibly the coldest morning of the year! — we drove to Stoughton, Wisconsin to take in the museum. Livsreise (Norwegian for “life’s journey”) focuses on the physical and cultural journey undertaken by Norwegian immigrants, as well as on the impact those settlers had on their adopted home. Uncle Phil and I were reminded in exhibit after exhibit of the resourcefulness of these hardy settlers, and the immigrant stories featured in the displays recalled similar stories passed down in our family.

But the museum made me wonder: Is there anything particularly “Norwegian” about today’s Norwegian Americans? As a rule, we don’t speak the language and have little contact with the culture, aside from an occasional nod to our roots at holiday meals. (For a hilarious take on Norwegian Americans by a Norwegian television program, check out “Alt for Norge”: https://youtu.be/EjY4AirrdLw?si=inNTUKuxZvx77reS). You might have an auntie who still knows how to make krumkake or paint in the rosemål style, but that’s increasingly rare.

Last month I went in search of this culture in what had been America’s largest Norwegian community — Bay Ridge in Brooklyn. In 1940, this part of NYC was home to the third-largest concentration of Norwegians in the world, after Oslo and Bergen. I had read online that the neighborhood’s beloved Norwegian bakery, Leske’s, had changed ownership and was now an Italian bakery called Il Fornaretto which still sold Norwegian favorites. Sadly, this is not the case. I did find a lovely bakery, but there’s nothing Scandinavian about its offerings. Similarly, there’s almost no trace of Norwegian culture in the surrounding community. Walking the length of 8th Avenue — once nicknamed Lapskaus Boulevard after the stew favored by Norwegian residents — I found few hints of a Norwegian-American past. Today 8th Avenue is a vibrant Chinatown.

Faint echoes of Brooklyn’s once thriving Norwegian community are all that remain.

In addition to being generally hard to find, Norwegian-American culture is arguably quite different from Norwegian culture. The separation of Norwegians from the motherland at a particular moment in history (mid-1800s to early 1900s) led to interesting divergences. Food culture provides some pertinent examples.

The two foods that many Norwegian Americans associate with their culture – the flatbread known as lefse and the preserved fish known as lutefisk – became less prominent in Norway once the economy improved in the early 20th century. These were, after all, foods rooted in the poverty of 19th century Norway.

Conversely, many of the food traditions that Norwegians most strongly associate with their culture – from cheese slicers to skolebrød (a sweet roll with custard and coconut) – are hard to find in a Norwegian-American kitchen, as these traditions came after the exodus. Americans of Norwegian ancestry tend to ignore these cultural divergences, let alone the differing political and religious views of their cousins across the pond.

Norwegian-American ethnicity is something sociologists like Herbert Gans, Richard Alba and others have termed a “symbolic ethnicity” — an ethnic identity that some people (e.g., white Americans) have the luxury of playing up or playing down as they see fit. One does not need to speak the language or have particular cultural knowledge to claim a symbolic ethnicity. One can simply opt in when it suits. Such asserted ethnic identities exist in stark contrast to ascribed ethnic identities: ethnicities that don’t just get trotted out around the holidays, ethnicities with deeper consequences for daily life.

Personally, this characterization of Norwegian-American ethnicity feels apt. And social observers during the immigrant era often commented on the ability and willingness of Norwegian immigrants to assimilate quickly. For instance, Norwegian scholar Ole Munch Ræder visited Wisconsin in 1847 and remarked that as soon as young men from Norway gain some success “they at once become strangers to their less fortunate countrymen and are very loath to admit their Norwegian origin.”**

Still, I find it interesting that after a century of very little immigration from Norway and after 200 years of successful assimilation efforts, there is still some ethnic feeling left among the Norwegian Americans. My hypothesis — unchecked by any real data or analysis — is that Norway’s major emigration period coincided with its nationalist movement, resulting in a critical mass of immigrants with nationalist sentiments. In this regard, Norwegian Americans may be more similar to German, Italian or Irish Americans than they are to their fellow Scandinavian Americans, as a national consciousness in Denmark and Sweden arose more gradually in the centuries prior to mass emigration. (What do you think of this hypothesis? Feel free to comment below!)

So far, I’ve contemplated the Norwegian diaspora from an immigrant-centric (and America-centric) perspective. But one country’s immigrants are another’s emigrants. To what extent does the diaspora figure into Norwegians’ collective imagination of their own history? And how do Norwegians think of their relatives in America? I’ll turn to these questions in a follow-up post.

* Semmingsen, Ingrid. 1978. Norway to America: A History of the Migration. University of Minnesota Press.

** see p. 49 in Fapso, Richard J. 2001. Norwegians in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Leave a reply to Jesse Rude Cancel reply