Norway is one of those countries – like Macedonia or Mongolia – that has a modest footprint today but once settled and ruled distant lands. This is not to say that Norway’s best days are behind it. But it does have a storied, almost mythic past. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the Old Kingdom of Norway did not leave behind much in the way of monumental architecture. Much of what was built was made of wood, and wood doesn’t tend to stick around.

But now and again in Norway you’ll come across a relic from this bygone era.

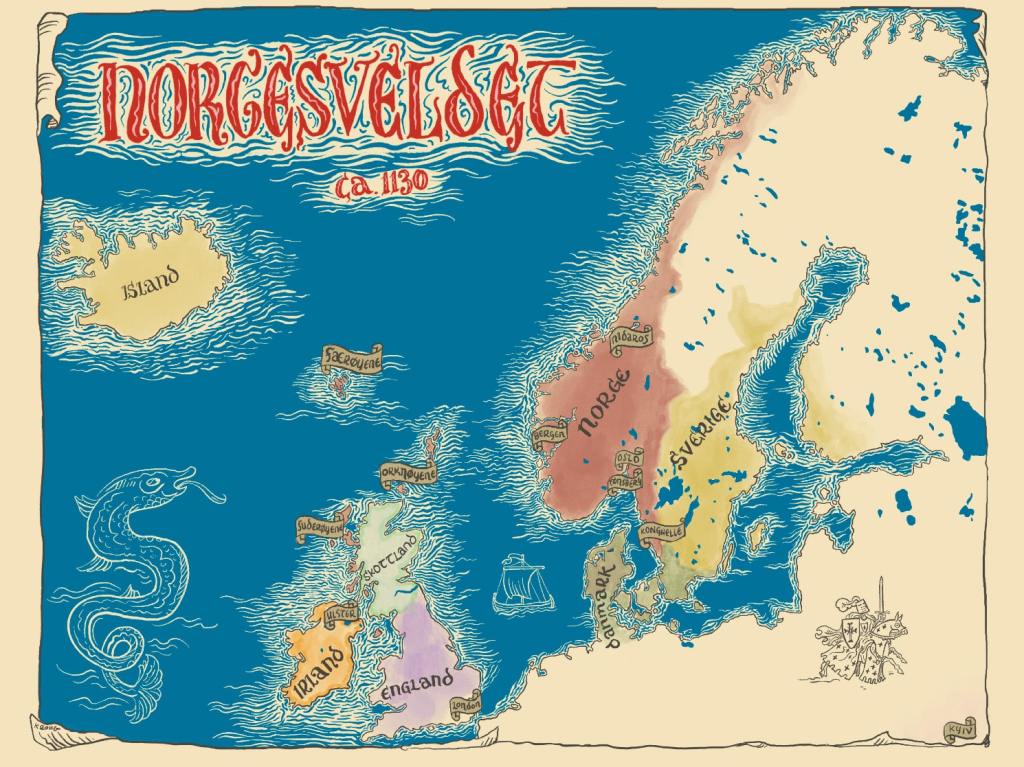

When Borgund Stave Church was built, circa 1200, Norway was going through a period of intense civil war — internal conflicts that didn’t end until about 1240. The kingdom’s holdings at that point stretched from Båhuslen in the southeast (now part of Sweden) to Iceland and Greenland in northwest. In between, the Kingdom of Norway ruled parts of Ireland and Scotland, as well as the Isle of Man, Orkney, Shetland, the Hebrides and the Faroes.

Central to the administration of this expansive kingdom was the Norwegian Church. Norway was becoming Christian in exactly the years when it acquired overseas territories (between about 1000 and 1150). Despite the kingdom’s strong association with Christianity, elements of pre-Christian style shine through in those early churches.

Prior to the Black Death in 1349, there were over 1,000 stave churches in Norway. Today only 28 are still standing (see www.stavechurch.com).

The Black Death was the beginning of the end of Norway’s “golden age.” In less than 50 years, Norway was absorbed within the Kalmar Union. The country’s population didn’t recover for another 300 years, by which point Norway was a jewel in Denmark’s crown. That diminished population could not sustain all those churches, and many were demolished. Several stave churches that remained intact during those years were later razed during the Reformation (post-1537).

The old stone churches of the early Middle Ages fared much better. There are over 150 stone churches from that era still standing in Norway, most of which were built between 1150 and 1250. On May 10th, I had the opportunity to visit one of them — Balke Church in Østre Toten, where my great-grandma Borghild Helgestad was baptized.

Mr. Roar Øksne, the former verger, was kind enough to give me and two of my local relatives (Hilde Iversbakken and Mathilde Hanssen) a detailed tour of this impressive structure. Mr. Øksne explained that Balke was probably built around 1170 but underwent major renovations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

He painted a vivid picture for us of what people experienced when they walked into the church in the Middle Ages. The windows were even smaller than they are today, making the interior dark. The parishioners had to stand during services, huddled together in the unheated building, and their participation in the service was minimal. In those days, Mr. Øksne explained, a church service focused more on the rituals between the priest and God — the congregation were mere witnesses to the event.

I wonder if this was true in all of Christendom, or if this was a holdover from how earlier generations of Scandinavians worshiped. I visited the University of Bergen Museum on May 21st, and a display there highlights how the image of Christ changed during the early Middle Ages in Norway. Three crucifixes are juxtaposed: the one at left from about 1150, the one at right from about 1275, and the one at back from about 1330.

The oldest of these, explained a guide named Thomas, is looking straight at you. The people of that time would never accept a God who bowed his head. He needed to be a strong leader you could follow into battle. He suffers but faces death with eyes wide open.

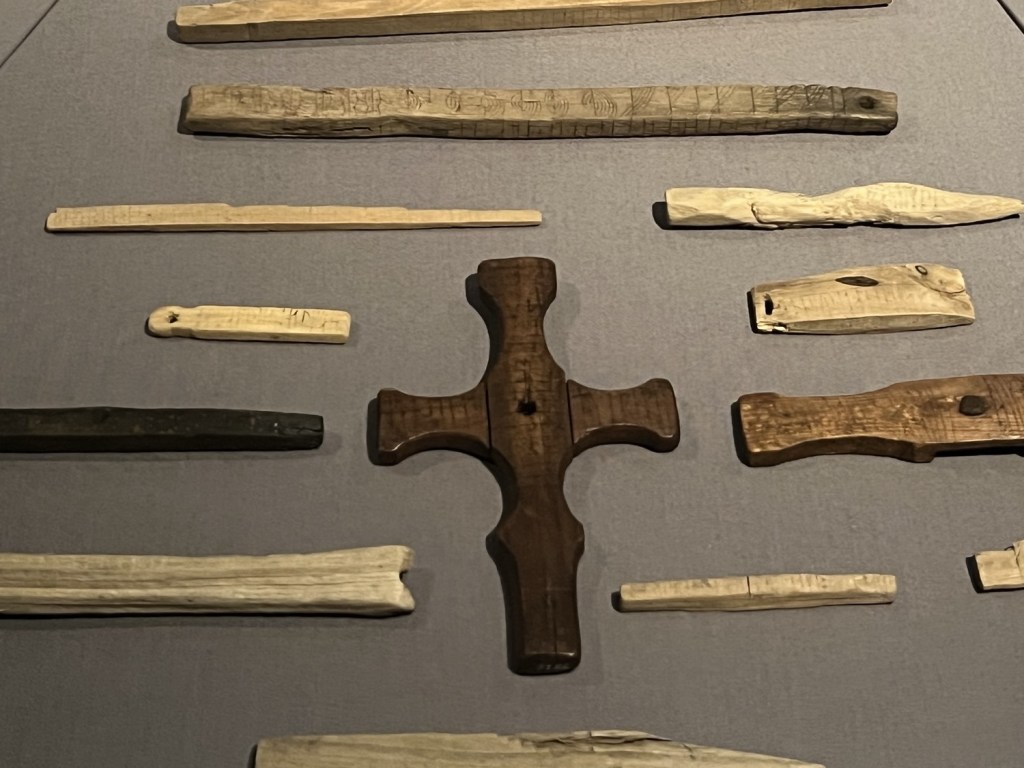

And so it is, I suppose, in all times of cultural transition. We transmit new messages using the vocabulary of the past. This was true in a literal sense in the early Middle Ages, as the older runic writing system — believed to have been Odin’s reward for sacrificing himself — was used to convey Christian blessings and prayers.

When we interpret the past, we naturally use the vocabulary of the present to understand it. This “back translation” allows for clarity, but of course something is always lost in translation. Much of what we know about Viking Era history and religion, for example, comes from the sagas written down centuries later by the Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241).

In Sturluson’s “histories”, the stories of historical figures blend with both Biblical and Norse legends. It can be hard to parse fact from fiction.

This morning (May 23rd) I had the chance to visit the National Museum of Iceland — a final stop before heading home. Here the 13th century is remembered differently: not as a “golden age” but as an era of subjugation under the Norwegian kings. It’s the period just prior — what we might call the Viking Era or what the Icelanders call the Age of Settlement — that is probably the most romanticized here.

Norse society’s transition in the early Middle Ages from pagan Viking to fully Christianized is particularly evident in Iceland. Unlike in Norway (and other lands), where those who failed to convert were put to death, Icelanders peacefully adopted Christianity through a democratic process. But they were allowed to worship as they desired in private.

Walking through a museum like this, I ponder how those who come after us will summarize our current times. What objects from today will find their way into future museums? Will the 21st century be seen as transitional as the 13th? Maybe they will marvel at how we embraced scientific ideas while still holding onto non-scientific beliefs — stumbling to fully face up to our prejudices, our social inequalities, and our impact on the environment. Only time will tell.

Leave a reply to Teddie H. Cancel reply