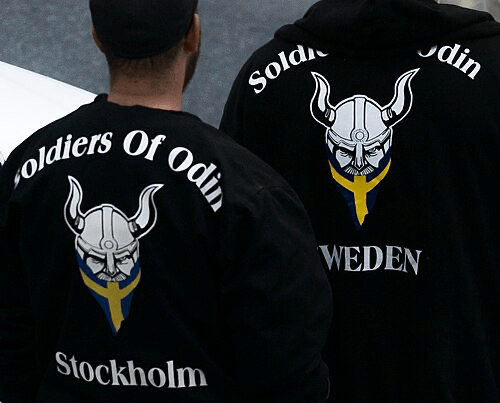

Pick any aspect of ancient Scandinavian culture – from Norse religion to runic writing – and do an online search. It won’t take you long to find groups and individuals who are co-opting this culture to serve white supremacist ideologies. The Nazis were of course fascinated with Norse culture, believing that it harkened back to a “pure” form of Germanic culture. They incorporated it into their national mythmaking and iconography. Likewise, they placed the so-called “Nordic race” at the top of a racial hierarchy supported by the scientific racism that was popular in European and American academia at that time. Those pseudo-scientific theories about a master race were not simply misguided; they led to the slaughter of millions of innocent people.

The misappropriation of Norse history, culture and symbolism didn’t die out with the Nazis’ defeat in 1945. White supremacism lives on and, if anything, has been emboldened by the regressive political movements taking place in the United States and across parts of Europe today. Thus, the misappropriation of Norse culture for racist ends is unfortunately still common.

I am always a bit wary of an author’s motives when I come across a discussion of Scandinavia’s historical cultures online. Is this author trying to assert the superiority (historical or current) of a particular ethnic or cultural group? Is there an implied hierarchy in the discussion of such peoples?

Given this history, people of Northern European descent who are captivated by their own ancestry can be a little suspect to me. Do they have an axe to grind? What’s their angle? And yes, if I came across my own blog online, I’d be asking those same questions. So, I sadly feel it necessary to offer some explanations here.

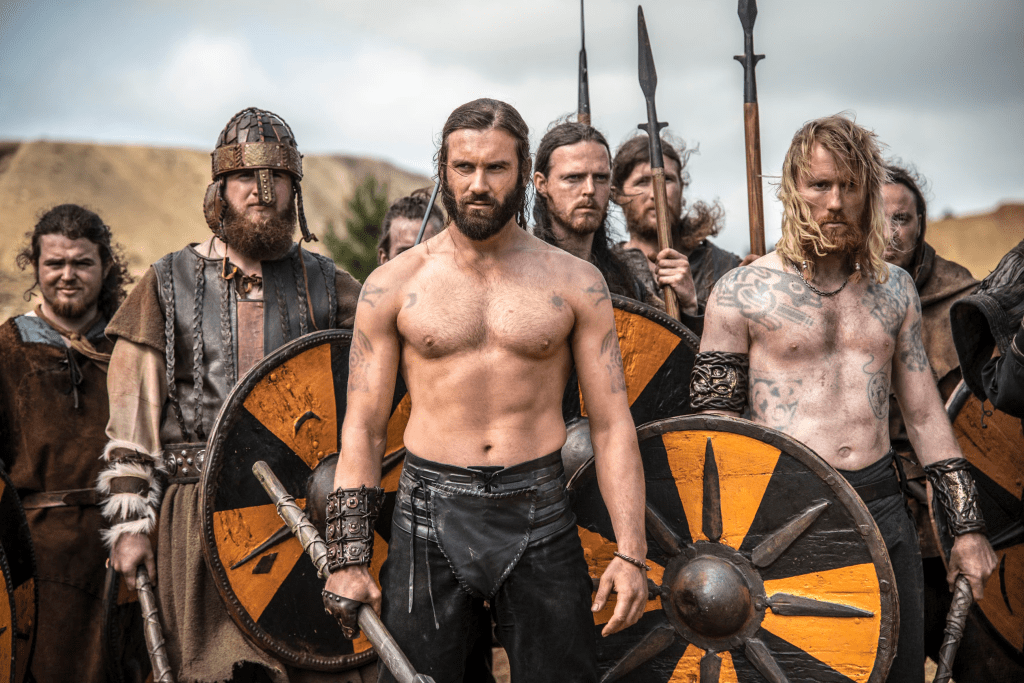

Norse culture – whether broadly or narrowly defined – has some quirky features worth exploring. The Viking Age, for example, presents us with contradictions. Was Scandinavia an isolated cultural backwater or a land of intrepid seafarers and explorers? Were the people easy converts to Christianity or pagan holdouts? Egalitarian or class conscious? Peace-loving farmers or violent marauders? Perhaps they were all these things. Our lack of knowledge allows the Viking Age to be a screen onto which our imaginations (and Hollywood) can project whatever suits.

As a culture that made its mark across the North Atlantic, Russia, and even parts of the Mediterranean and Near East, the Norse are worth a look for anyone inquisitive about world history. Personally, I am interested in how the Norse encountered other peoples of the world and how these cultures mutually influenced one another. And as a family historian, I am curious to find out what aspects of ancient Scandinavian culture might have been preserved in modern practices and ideas – practices and ideas which my ancestors may have even brought with them across the water.

But I strive to approach all my inquiries with a healthy dose of cultural relativism and social constructionism. Both viewpoints are currently under attack in America today as being “woke” and neither are typically mentioned in genealogical writing. They deserve some amplification here.

Cultural relativism refers to anthropologist Franz Boas’ idea that no culture can be understood according to the standards of another culture; it must be understood within its own cultural context. Were the Vikings violent by 21st century standards? Certainly. Is this an appropriate context to judge them by? Certainly not. Cultural relativism is the natural cure for ethnocentric and present-centric views.

Social constructionism refers to Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann’s idea that the social phenomena we observe are not simply “out there” – objective realities to be discovered. Instead, they are in large part the product of what we have been conditioned to observe through our interactions with others. Do “white people” exist? Biologically speaking, no. But the social category can exist within a particular social context and such a categorization can have real world effects on life outcomes. This may sound like splitting hairs, but the implication is that if a social phenomenon (like a race, ethnicity, nationality or culture) is a construction, it can be re- or de-constructed. Its boundaries can shift, become porous or solid, or be erased entirely. New meanings can get attached to old categories. Social constructionism is therefore the natural cure for essentialism – the circular, ‘common sense’ logic that things just “are the way they are.” The social constructionist says, “No – things come to be the way they are through a history of interactions, and subsequent interactions can change them.”

These postmodern approaches to culture have their drawbacks. If taken to the extreme, they beg the question: can we say anything about anything? I would argue that any inquiry – academic or personal – requires definitions and categories, and therefore some of the postmodern navel-gazing must be bracketed off, at least temporarily, for us to summarize knowledge and make sense of our world. I would also argue that no amount of postmodernism saves us from the reality that inquiry itself is value laden. We can make good faith attempts to conduct our inquiries free from cultural bias, ethnocentrism and essentialism, but the act of inquiry itself – our choice of subject and methods – makes a statement about our values and positionality. The real question is whether we are aware of these or not.

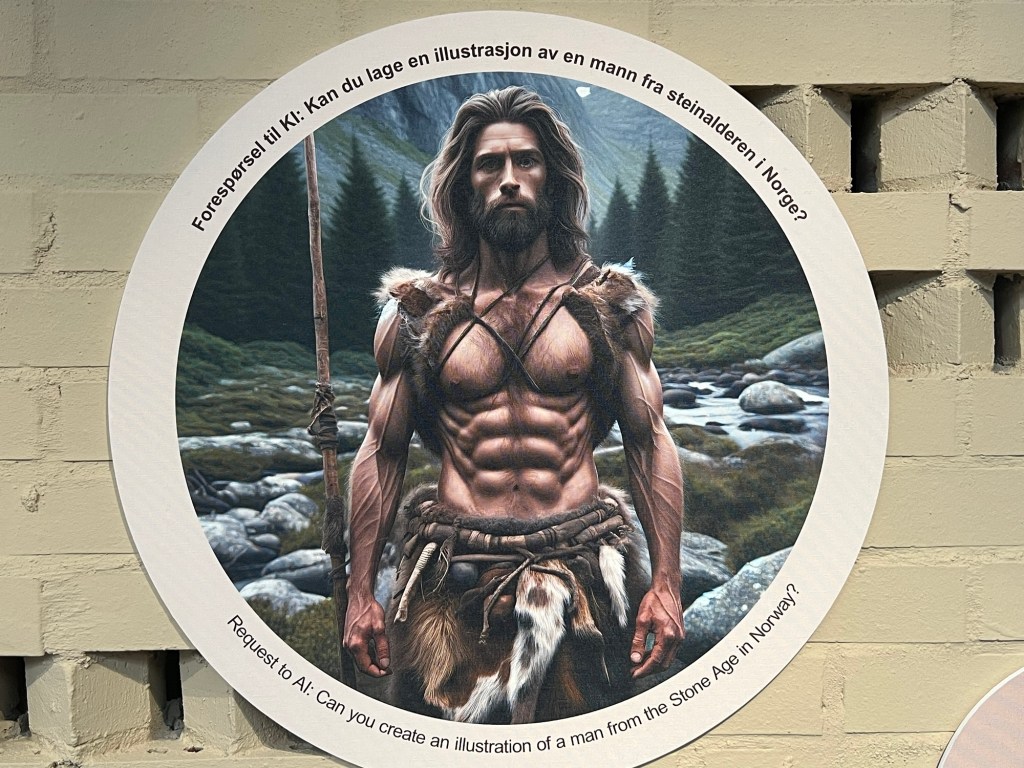

To bring this essay back to the uncomfortable truth I laid out at the beginning – that Norse culture has been co-opted by racist ideologues over the past century – is it possible to study Norse culture without reinforcing such ideology? I certainly hope so. But I am also aware that one person’s anti-racist inquiry can become fodder for another’s racist inquiry. Once knowledge is put out into the public sphere, it can become perverted by another person’s agenda. I am keenly aware, for example, that I’m writing these words in an era in which artificial intelligence technology can scrape up my thoughts and repackage them for different purposes, different audiences. I can’t possibly know how my words will be used going forward. But I can state my intent and clarify my own views: that Norse culture is worthy of study – not because it encapsulates the lifeways of a supposedly superior people – but because it has been one of countless cultures engaged in a historical dialogue with the rest of world, and some of its internal contradictions are – in my opinion – interesting in and of themselves. And I can also admit my own bias, my own “angle”: that part of my curiosity about this culture relates to how aspects of it may have filtered down to modern practices and folk customs, and perhaps even to those of my own ancestors.

Leave a comment