-

Notes from the heartland (Part 5: Home)

I am home now after my road trip, a road trip long enough to permit some reflection. If you’ve read my previous posts, you won’t be surprised that I’ve been reflecting on our place in history. We Americans are living in a challenging time right now in terms of historical storytelling. Challenging but not unprecedented. In the 1950s, during the Red Scare, Americans who dared point out inconvenient truths about the nation’s historical inequities were labeled socialists, communists, or un-American. Today the ruling faction in Washington and in many states has decided that certain stories about America’s past shouldn’t be told, at least not in their entirety. Historical markers, national museums, and chapters of school textbooks are being revised in the belief that if such stories are fully told, young Americans will grow up hating their country.

I have a different view. Mine is that if young Americans don’t have a clear sense of how events unfolded, they’ll grow up loving an image of their nation that doesn’t match reality. They won’t actually have an opportunity to fall in love with America, only a whitewashed or romanticized version of it. I believe, moreover, that without sharing the breadth of our collective experiences — even those experiences that are uncomfortable or contradict our stated values — our history doesn’t make much sense. And if we can’t make sense of our past, what hope do we have of transcending it?

One such contradiction was embedded in the nation’s fabric from day one and it’s with us today. This contradiction is painfully obvious to anyone who knows their history, and I was constantly reminded of it during my travels through the heartland. I’m not breaking any new ground by pointing it out, but it does run counter to the sanitized narratives that America’s right-wing would have us parrot (e.g., the rewriting of the Wounded Knee Massacre).

The “land of the free” was carved out of other people’s land, people who were systematically excluded from it.

Once we come to grips with the totality of that contradiction, it’s hard to look at America in the same way. Over the past week, I’ve been writing about my American settler roots, and it’s quite possible (as I have done in the last few posts) to write about frontiers, pioneers, and homesteaders, and cleanly skip over this contradiction.

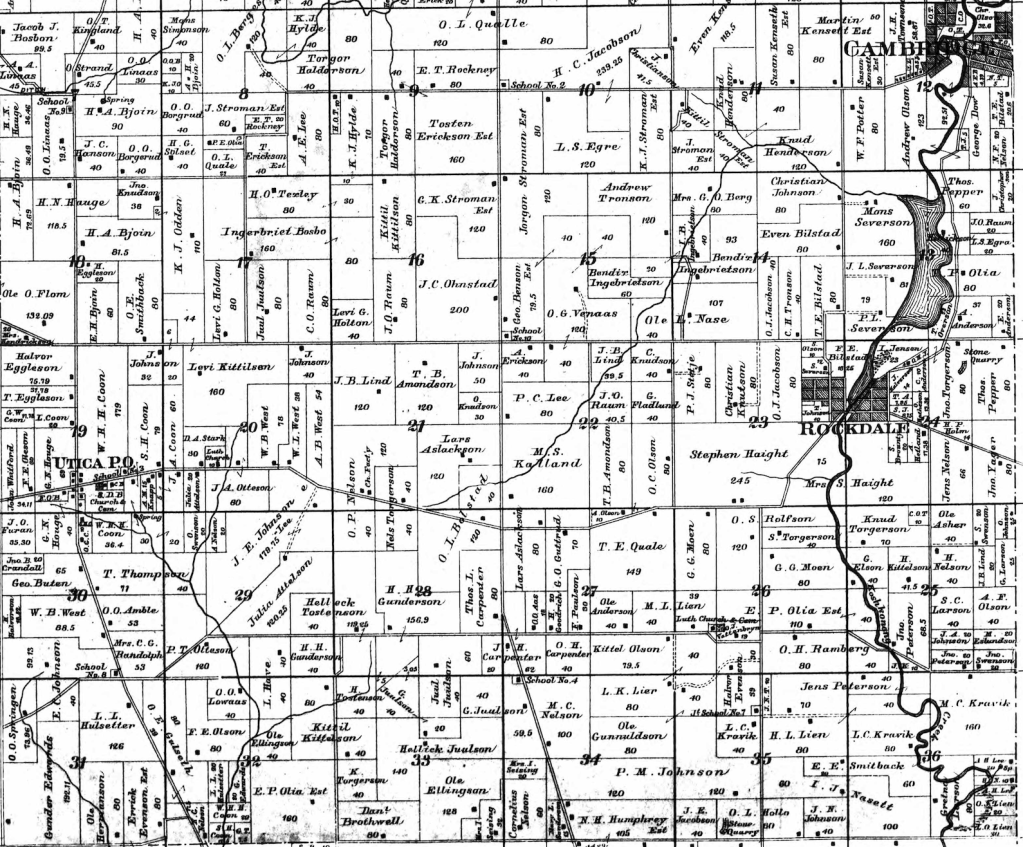

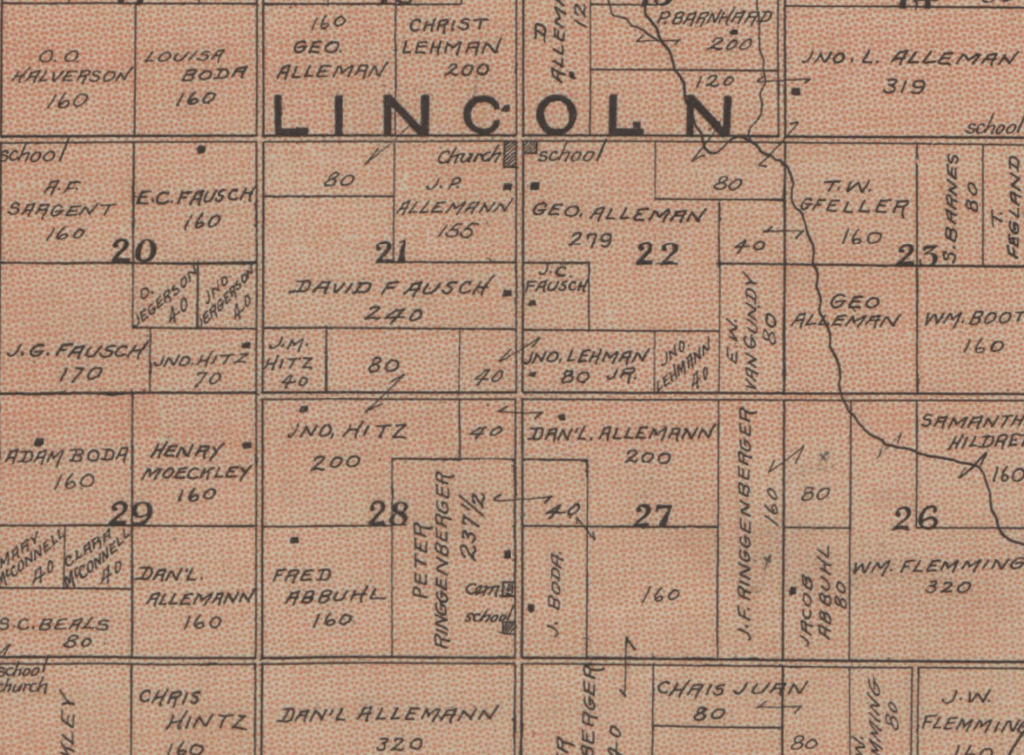

Plat of Christiana Township (6 N, 12 E of the 4th Principal Meridian), Dane County, Wisconsin (1890), where several ancestors on both my mom and dad’s sides settled between 1849 and 1904 Settler-colonial geography is linear — millions upon millions of acres of neatly surveyed farm land, little squares as far as the eye can see. But this geography was superimposed upon the native geographies that preceded it. Additionally, native geographies from the east were transferred westward by various forms of forced migration. These different geographies interpenetrate one another in America’s heartland, and the history of native land dispossession can be found everywhere you care to look: it’s written into the names of towns and counties, written into forgotten roadside markers, written into the smattering of reservations that break up the settler grid.

My own understanding of these other histories, these other geographies is woefully inadequate. Somewhat belatedly I am trying to rectify that. What follows are a handful of photos and reflections from three stops along my route.

Oklahoma

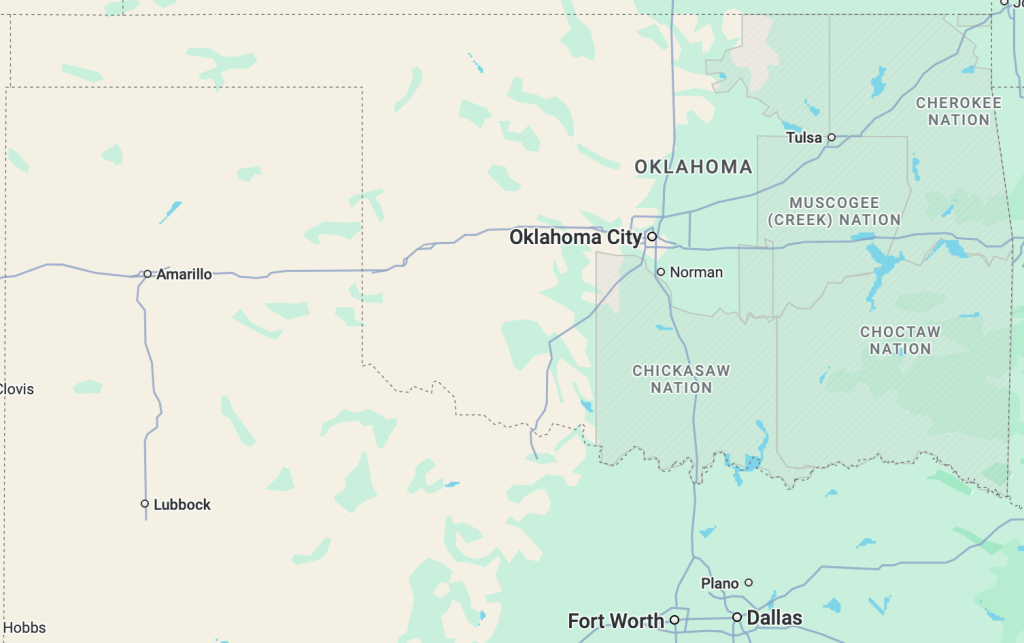

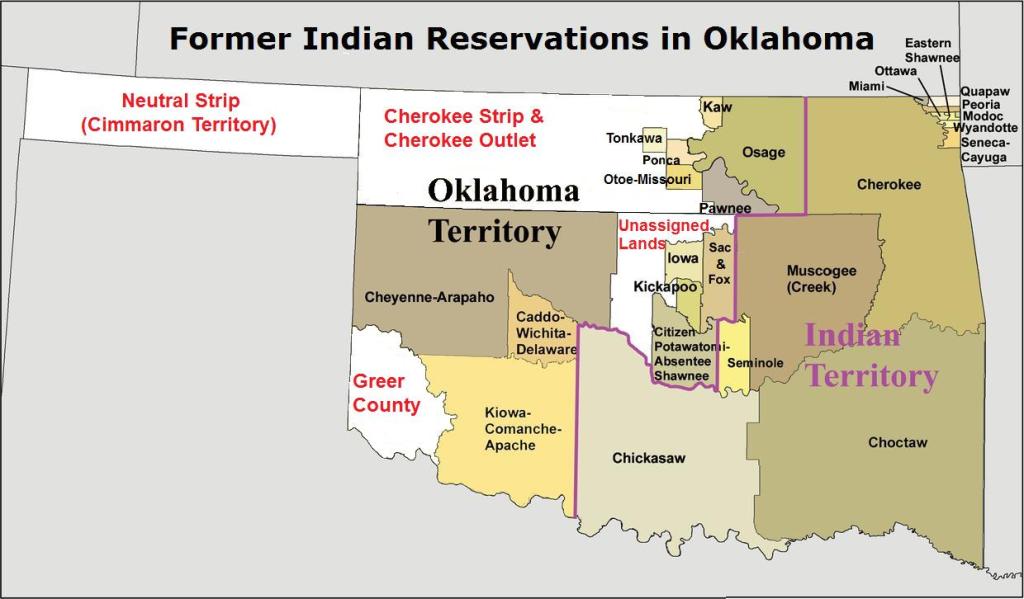

Driving to Texas and back afforded me two journeys through Oklahoma: one from the northeast corner heading southwest (via Tahlequah and Muskogee), and the other headed due north from Fort Worth (via Oklahoma City). In criss-crossing the state, I drove through at least seven reservations. The conglomeration of tribal authorities here is owed to the fact that much of what would become the state of Oklahoma was once “Indian Territory” — lands set aside by the U.S. Federal government for indigenous peoples after being forcibly removed from their homelands out East.

The core of Indian Territory was made up of land granted to what were then called the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw) after their dispossession and forced march across the South in the 1830s and 40s — the infamous Trail of Tears. But even this set-aside territory was whittled away by the federal government in the post-Civil War era. Factions of the Five Tribes had sided with the Confederacy, and the Union took a heavy-handed approach to dealings with them after the War. Nationally this was a period in which native children were sent away to boarding schools in order to “civilize” them, and white settler-colonists squatted on native lands with impunity. The federal government also resettled many Eastern tribes on lands belonging to the Five Tribes during this time.

Map by Kmusser – File:Okterritory.png, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link The Dawes Act of 1887 codified the federal government’s assimilationist approach to Native America — communal native lands were to be converted into individual landholdings. This paved the way for the carving of Oklahoma Territory out of Indian Territory in 1890, and eventually — after a failed bid to form the native State of Sequoyah — for the creation of the State of Oklahoma in 1907. The settler grid had been imposed on Indian Territory. (For a more nuanced explanation of all of the above, I highly recommend Ned Blackhawk’s excellent history, published in 2023, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. See especially Chapter 9, “Collapse and Total War: The Indigenous West and the U.S. Civil War”.)

Cherokee National History Museum; Tahlequah, OK (Cherokee Nation)

Five Civilized Tribes Museum, Muskogee, OK (Muscogee/Creek Nation) Winnebago Reservation, Nebraska

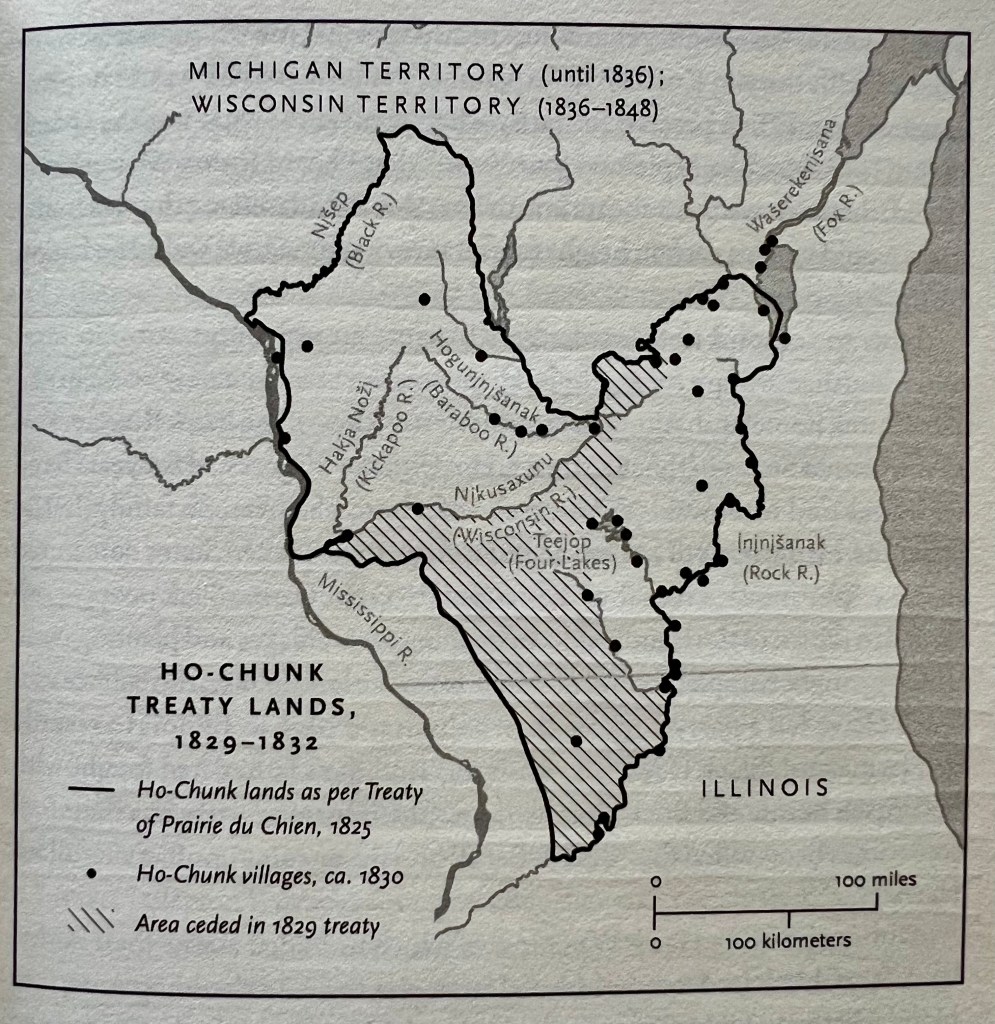

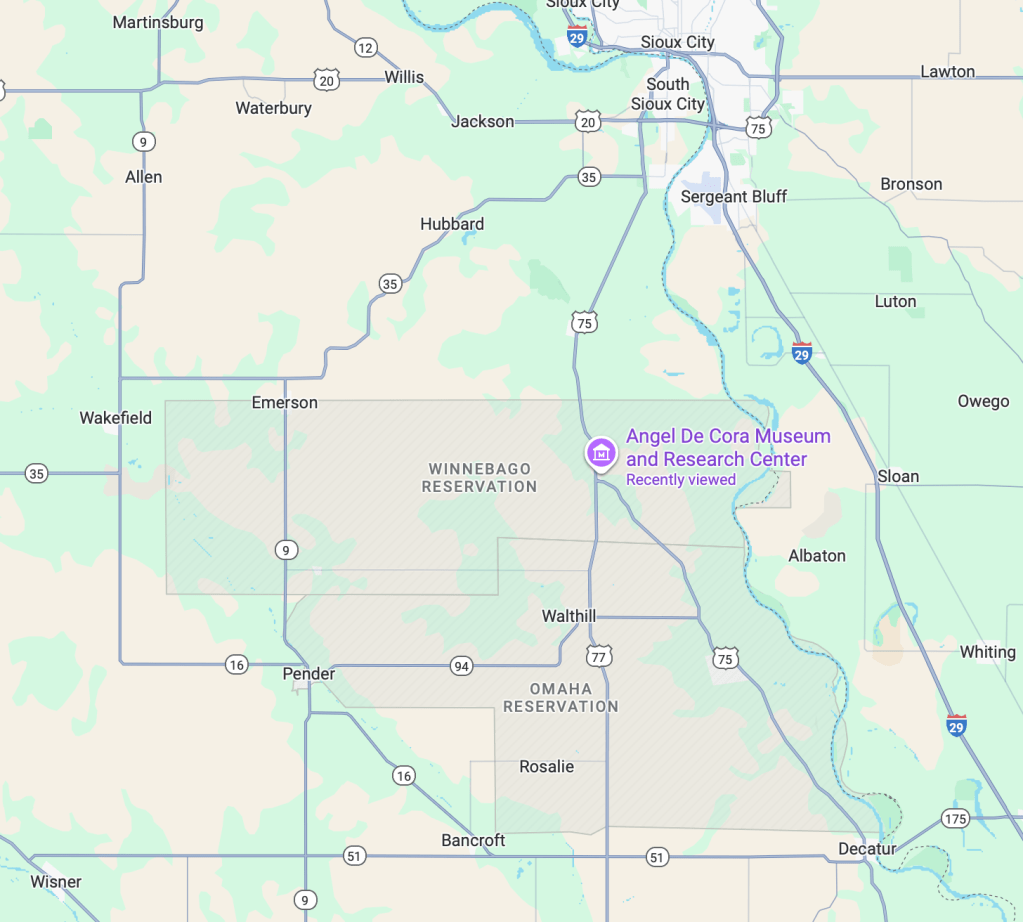

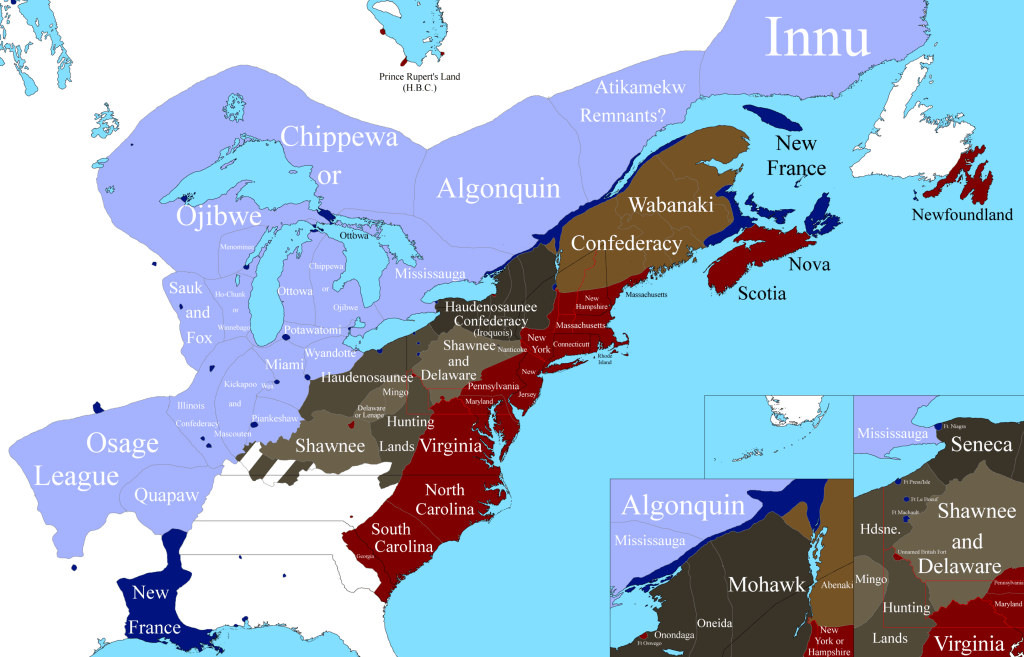

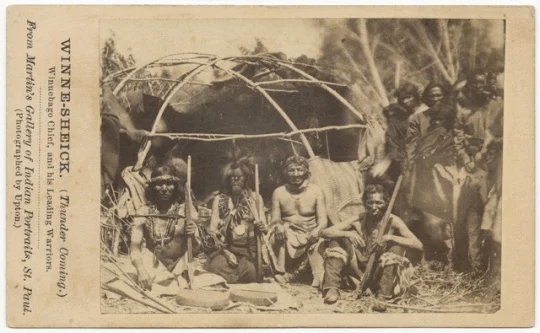

Photo of unnamed Wisconsin Ho-Chunk men, Angel De Cora Museum & Research Center, Winnebago, NE (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska) Yesterday I drove through lands belonging to the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. Until the colonial period, the Winnebago — also known as the Ho-Chunk — controlled much of southern Wisconsin where my ancestors settled in the mid- and late-19th century. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Ho-Chunk numbers were greatly reduced by disease and by warfare with tribes that had been pushed into their territory due to conflict and colonization in the East.

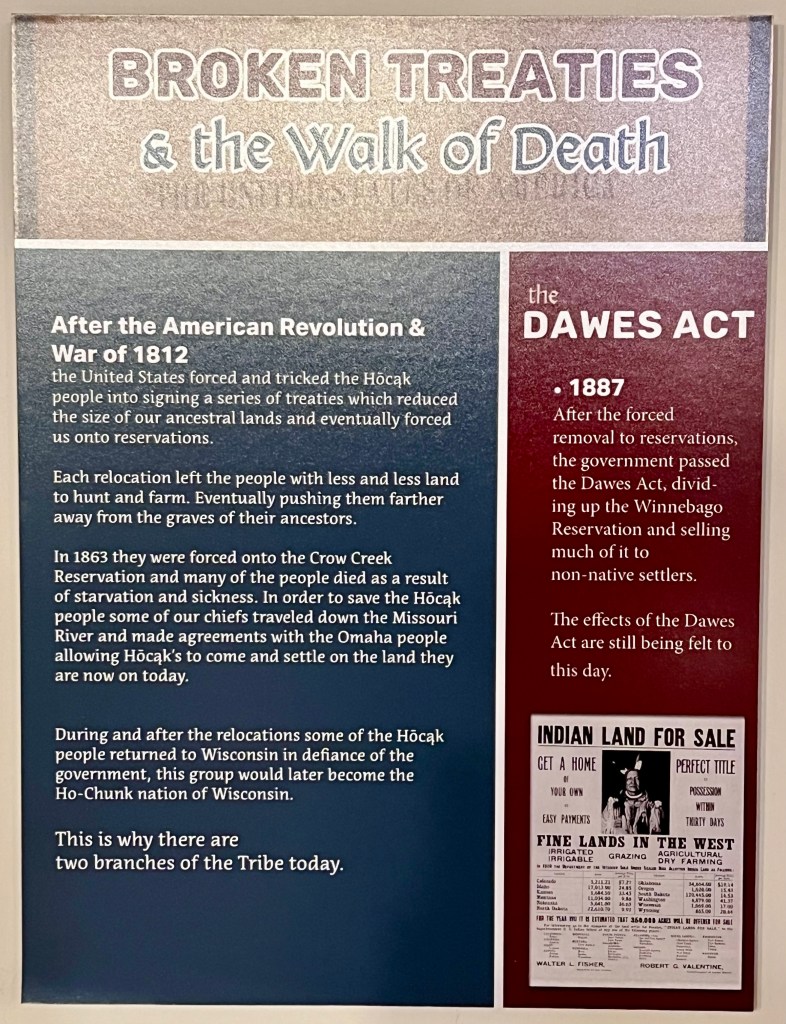

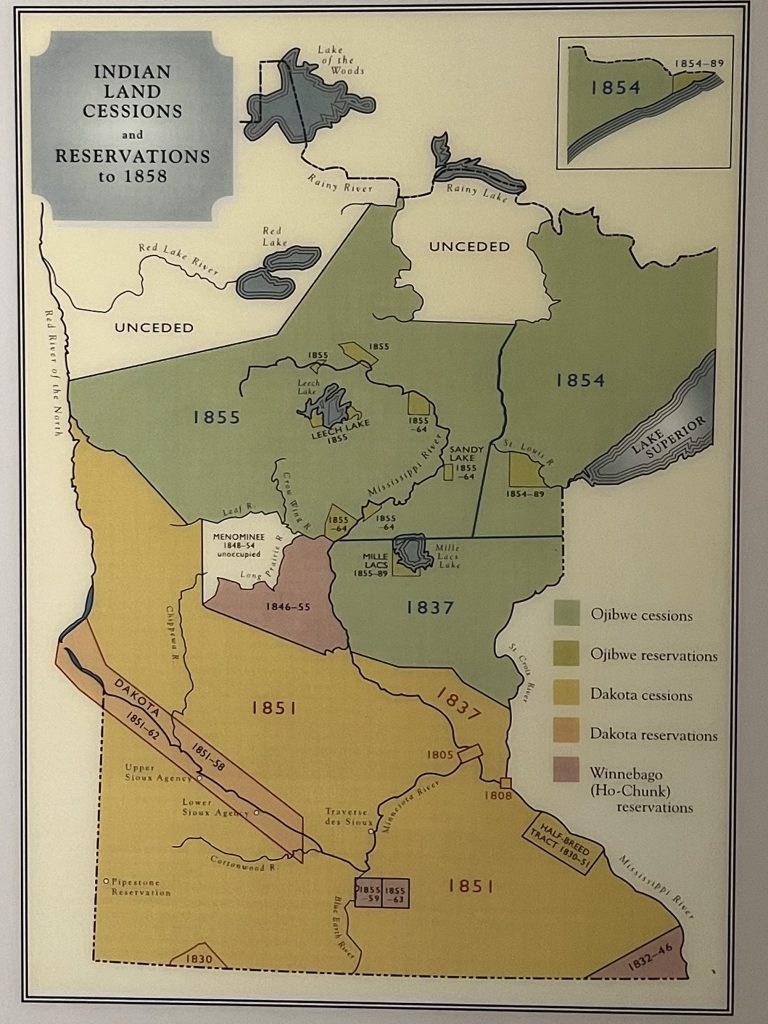

Map from p. 27 of Kantrowitz’s (2023) Citizens of a Stolen Land But theirs is a story of great resilience despite a concerted effort on the part of white settlers to sweep them aside. Through a series of unequal treaties, all federally recognized Ho-Chunk lands in Wisconsin were eventually ceded, and the Ho-Chunk were forcibly relocated to a reservation in Iowa in the 1830s. But local white settlers objected to the Ho-Chunk presence and they were again forcibly removed, this time to Long Prairie, Minnesota. The Ho-Chunk were dissatisfied with Long Prairie, and they negotiated a move to Blue Earth, Minnesota, where the topography was more similar to their homelands. After the Dakota War (see next section), the Ho-Chunk were accused of disloyalty, despite not having participated in the conflict. They were exiled to Crow Creek, South Dakota, a dry and desolate camp along the Missouri. Faced with starvation, the Ho-Chunk leadership negotiated with the Omaha people to secure the current reservation in Nebraska.

Each of those forced moves, like the Trail of Tears, disrupted the lives and livelihoods of the Ho-Chunk people and many didn’t survive. The Ho-Chunk refer to these involuntary relocations as the Walk of Death. In spite of the terrible conditions, a group of tribe members persisted, surviving to form the Winnebago Tribe that exists in Nebraska today.

Display at the Angel De Cora Museum & Research Center, Winnebago, NE (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska) Furthermore, at each stage in this long history of dispossession, there were Ho-Chunk people who nonviolently resisted. Some individuals and families secretly remained in or traveled back to Wisconsin. Some even managed to take advantage of the Homestead Act to become landowners on their ancestral lands. It’s for this reason that a second federally recognized Ho-Chunk tribe exists, headquartered in Black River Falls, Wisconsin, despite not having a reservation in the state.

Display at the Angel De Cora Museum & Research Center, Winnebago, NE (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska) Yesterday I had the opportunity to get to know this history a little at the Angel De Cora Museum in Winnebago, Nebraska. The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska also provides a brief history of their people at this link. For a detailed account of how the Ho-Chunk people managed to survive the various trials of the 19th century, I highly recommend Stephen Kantrowitz’s (2023) Citizens of a Stolen Land: A Ho-Chunk History of the Nineteenth-Century United States.

Visiting the Winnebago Reservation, I was struck by the irony that my ancestors who had attempted to settle a few miles away (see this post) had been able to pack up and head “home” to Wisconsin when their crops failed. Most Ho-Chunk, however, did not have this luxury.

Angel De Cora Museum & Research Center, Winnebago, NE (Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska)

The museum melds contemporary expressions of Ho-Chunk life and culture with historical accounts, emphasizing the continuity and persistence of the Ho-Chunk people Mankato, Minnesota

A couple months ago, I wrote a little about the Dakota War of 1862 and the imprisonment of the Dakota people at Fort Snelling in the wake of the conflict (see this post). The Dakota people are indigenous to large parts of what is now Minnesota and western Wisconsin. After the uprising, the Dakotas were stripped of their lands in Minnesota and exiled to Nebraska, North and South Dakota, and Canada. This was contrary to multiple treaties signed by the Dakota tribes and the U.S. government, which had promised the Dakotas land in Minnesota and economic assistance — in the end, they got neither.

Display at the Treaty Site History Center, Traverse des Sioux (near St. Peter, MN) But to their credit, many Dakota people, similar to the Ho-Chunk, found ways back into their ancestral lands, and Minnesota is today home to four federally recognized Dakota tribes: the Shakopee Mdewakanton, Prairie Island Indian Community, Upper Sioux Community, and the Lower Sioux Indian Community.

I made a stop in Mankato today to visit the site where 38 Dakota men were publicly hanged in 1862 for their alleged involvement in the Dakota War. This was the largest mass execution in U.S. history. You feel the weight of history in a place like this, revisiting an episode from our past that we’re rarely taught. (For an excellent reflection on how this history has come to be remembered, I recommend this essay.)

Photos from Reconciliation Park, Mankato, MN History like this can be unsettling for Americans such as myself who are the descendants of the first white settlers in the Midwest. For me, fully seeing this history means coming face to face with the fact that my ancestors and I have been beneficiaries of “Indian removal” — policies and practices that were at best unfair and at worst genocidal.

But feeling unsettled isn’t always a bad thing. It can open us up to nuance, clarity, and insight. A deeper understanding of how Native America intersects with settler-colonial America doesn’t make me hate my ancestors. It expands my perspective of them beyond the two-dimensional pioneers we meet in old Westerns and Disney films. When we start seeing indigenous peoples and their histories as intimately connected with the histories of those who colonized America, we can imagine new possibilities for historical storytelling — possibilities that honor the complexity of the American past.

Rōksu hikixarac (bandolier bag), made in Wisconsin in the late 1800s with design influences from Scandinavian settlers (Angel De Cora Museum, Winnebago, NE) -

Notes from the heartland (Part 4: Nebraska)

Starting out from Fort Worth yesterday, my canine companion and I traced the Chisholm Trail up to where it peters out near Salina, Kansas. From there we headed due north on a lonely stretch of US 81 into the endless plains of southern Nebraska. Between the Platte and Elkhorn rivers, the terrain changes to gently rolling hills. The farms are so large here that it can be hard to spot a building on the horizon. Post-harvest, these fields could almost be mistaken for sand dunes. Eventually we reached our destination, a tiny town called Wisner.

Round ‘em up, Spence! (Sundance Square, Fort Worth, TX)

They don’t call it the Great Plains for nothing (Hebron, NE)

Photo op in Wisner, NE Walking along Wisner’s quiet streets, my dog Spence looks at me as if to ask, “Why are we here?” You may be wondering the same thing. To explain, I need to take you back to the early 1870s.

Downtown Wisner My great-great grandparents, Albert Jens Johnson and Julia (Guri) Anne Torbleau, were part of the first generation of my family to be born on American soil (see Chart B on this page). Albert’s parents had come to Deerfield, Wisconsin in 1850 (see this post) and Julia’s had come in 1849 (see this post) — both couples originating in small communities in Western Norway. Albert and Julia came of age in the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War, when America’s westward ambitions were reaching their zenith. Steeped in this culture of western expansion and growing up on their parents’ stories of forging a new life in a new land, is it any wonder that Albert and Julia dreamed of doing the same?

A family history written in the 1970s by Aunt Glenrose (Albert and Julia’s youngest child) records that Albert and Julia met at one of the socials or house parties put on each weekend by the community’s Norwegian residents. The 1870 Census shows Albert and Julia still living in their respective homes. Albert is 17 and listed as a carpenter’s apprentice. Julia is 15 and listed as “at home”, though Glenrose’s history states Julia worked in the household of Dr. Fox in her youth.

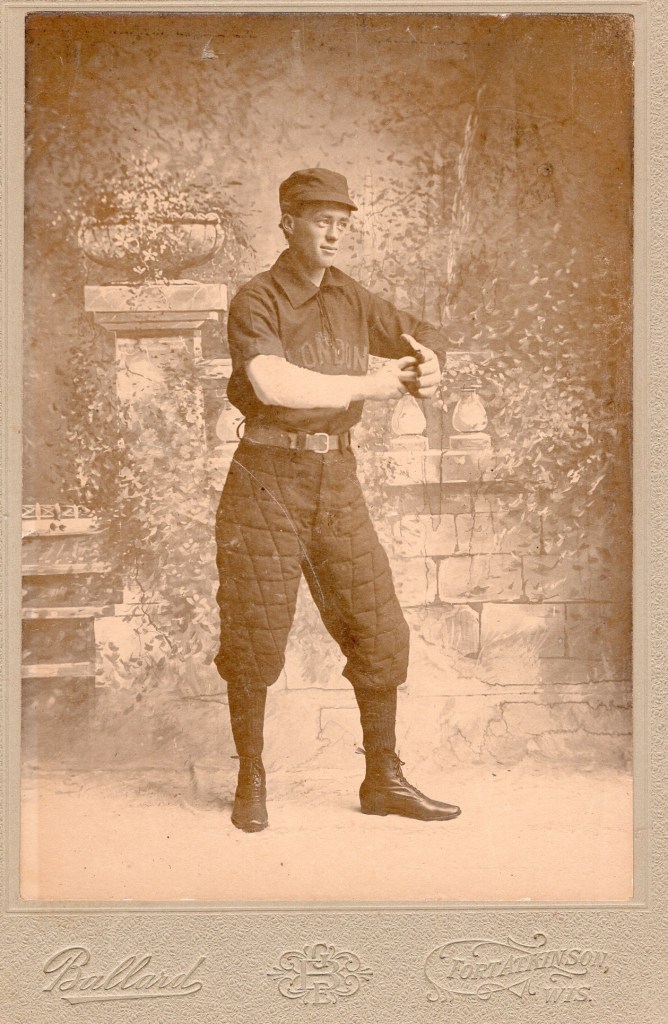

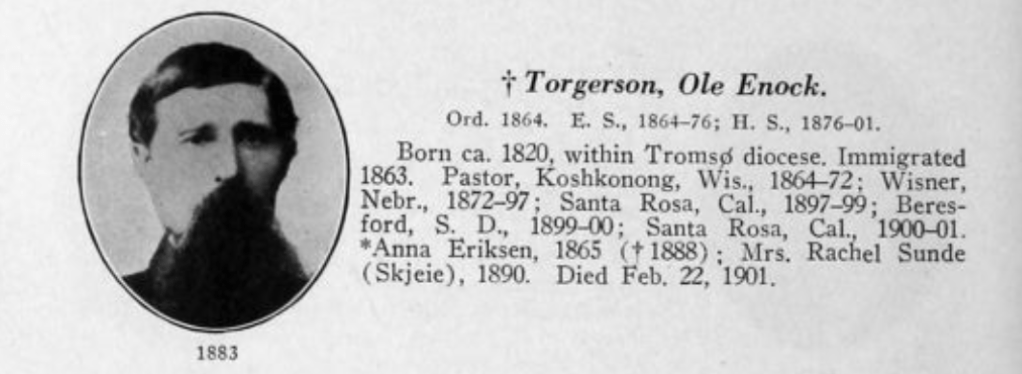

According to a newspaper article from the Newman Grove Reporter, a large group of Norwegians left Deerfield, Wisconsin for eastern Nebraska in 1872, traveling together in a convoy of prairie schooners.* They comprised “a train of ten wagons, seven horse teams and three ox teams, and arrived at Wisner, Nebraska on June 25, 1872.” The group included Ole E. Torgerson, a Lutheran pastor in the Haugean tradition, who “had great influence not only as a spiritual teacher but as a business man, advisor and promoter of the welfare of the pioneers…” I’m inclined to believe that Albert Johnson was among the pioneers who joined this wagon train.

The state road signs in Nebraska feature a covered wagon Glenrose wrote that “[Albert] went to Wisner, Nebraska and worked as a carpenter. He built a house and wrote for my mother to join him.” They married soon after Julia arrived, on December 7, 1873, at the ages of 20 and 18, respectively. My guess is that Albert accompanied Rev. Torgerson and the others from Deerfield in 1872 and that Julia arrived the next year, perhaps via the newly built railway. Evidence linking Albert and Julia to the group of pioneers in the newspaper article is slim: it’s simply that the timing seems too perfect to be a coincidence, and the man who officiated Albert and Julia’s marriage in Wisner, Nebraska was none other than Ole E. Torgerson.**

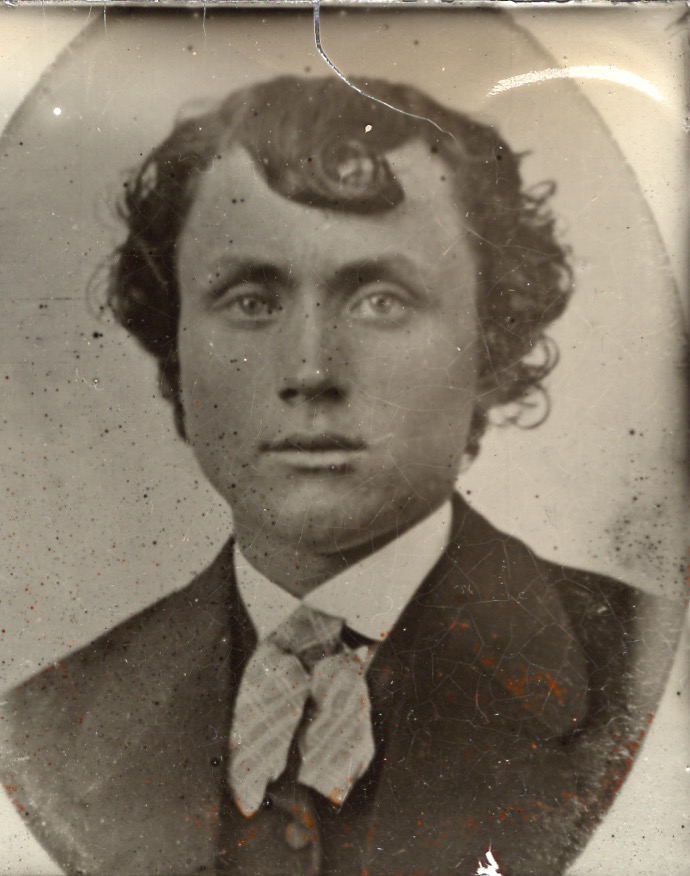

Albert J. Johnson as a young man

Julia (Guri) A. Torbleau Johnson as a young woman Albert and Julia only lived in Nebraska for six or seven years (1873-1879) and then they packed up and headed back to Wisconsin. Glenrose’s history provides the best information we have as to why:

“The varying prairie weather made crop prospects a gamble every year. Some years were dry and the crops seared in the fields, while strong winds across the prairie never ceased blowing dust. Farms had to be spread miles apart in order for a man to have enough acreage to make a living. With nothing but a sea of wheat between the houses, loneliness was a hardship. Hordes of grasshoppers were always a problem, some years being worse than others. They devoured crops and gardens, stripping the prairie and many farmers were forced to desert their holdings. Albert and Julia Johnson, ruined by a plague of grasshoppers were forced to return to the home of their parents” (Glenrose Johnson’s family history, pp. 7-8).

Julia and Albert Johnson with their first child Andrew (photo probably taken in Wisner, NE around 1876) Glenrose’s explanation tracks with historical accounts. An unimaginably large swarm of grasshoppers wreaked havoc across multiple states in the summer of 1874. Nebraska farmers were revisited by smaller swarms in ‘75 and ‘76 (see this link). After having their crops decimated several seasons in a row, Albert and Julia had little choice but to return to Wisconsin. After all, they now had little ones to consider.

Illustration of the grasshoppers stopping a train (source) Julia had given birth to their first three children in Nebraska: Andrew, Nels, and Art. Sadly, of these three, only Art would grow to adulthood. A couple years after returning to Wisconsin, both Andrew and Nels came down with a severe case of measles (what Glenrose calls “black measles” in her history). They died within hours of each other on the same day, February 4, 1882. Andrew was six and Nels was four. The family was devastated.

A photo I took in 2019 of the conjoined gravestones for Andrew Oliver and Nels Oscar Johnson, St. Paul’s Liberty Lutheran Church Cemetery, Deerfield, Wisconsin

These articles of clothing once belonged to one of the little Johnson boys who died in 1882. They are now in the care of my great-aunt Helen. Photo courtesy of Aunt Helen’s daughter, Julia Reed Meyers (namesake of Julia Johnson). Despite Albert and Julia’s hardships, Albert’s sister Carrie and her Danish fiancé Jens Kringel decided to try their luck in Nebraska. They left in 1881, married, and had their first two children in Wisner. But within five years the Kringel family retreated to Iowa where Jens’s relatives lived. Farming the Nebraska prairie in this era was clearly a struggle.

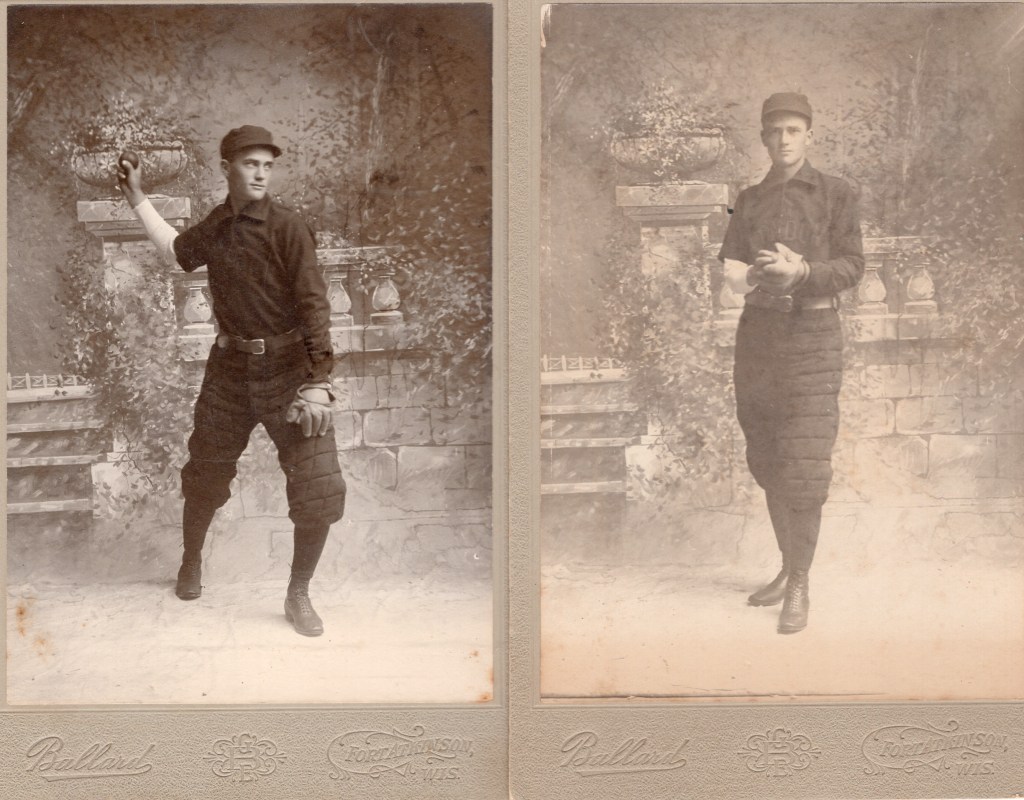

Albert and Julia went on to be modestly successful farmers and small business owners in Wisconsin, raising eight more children there. Many of these children, like my great-grandma Jessie, would grow up to have large families of their own. Tragically, the Johnsons’ fifth child, named Andrew after their firstborn who died in 1882, passed away at age 25 from a ruptured appendix. Andrew and his brother Art had been keen baseball players in their youth.

Albert and Julia’s fifth child, Andrew Johnson (1883-1909)

Art Johnson (1879-1967), the only Nebraska-born Johnson to live to adulthood Even though the family had moved back to Deerfield when he was a child, Art ended up marrying Isabel Doxstad — daughter of Ole and Oline Doxstad, who had been part of the same group of Norwegians to settle in northeast Nebraska. So it would appear that despite the Johnsons’ return to Wisconsin, some Nebraska ties were maintained.

When I look at my ancestors’ faces, staring out from old photographs, I see a kind of quiet determination, a resolve to make the best of their lives, no matter what destiny had in store.

Albert and Julia Johnson (Wisconsin, early 1930s) My great-great grandpa Albert Johnson liked to compose poetry, and you can hear this determination to stay positive in his verses. As the sun sets here on the prairie, I leave you with one of the poems that Albert’s daughter Glenrose preserved in her family history. This is “Once in a While”:

Once in a while there comes a joy

Which makes the tired old man a boy

And brings to the patient mother's eyes

The light of a schoolgirl's glad surprise.

Some little pleasure, too sweet for words

Like the June day song of the summer birds.

Then the bitterness of the life we know

The cares, the trials, the sting of woe

Are all forgotten, and glad we smile

Once in a while.

Once in a while life lifts its mask

And laughs us out of the dreary task

And shows us a world for a little time

That is fairer far than a poet's rhyme;

For the sunshine's out and skies are blue

And joy drips down like the morning dew

And never an old man grumbles low

Of aches and pains that are his to know

For the hours are dressed in their richest style

Once in a while.

Once in a while the cares depart

And peace comes into the aching heart

And the old roof rings with a song of glee

And life is glad as it ought to be.

Then we who have struggled and grieved and wept

Rejoice to think that the faith we've kept.

Our friends are near and this life seems good

And much we have doubted is understood,

For we glimpse the goal of the rugged mile

Once in a while.

A farm just outside Wisner

* History of the Pioneers. Halderson, H. (1930, April 2). Newman Grove Reporter. https://www.familysearch.org/en/memories/memory/181576246

** I think it’s also significant that Albert’s parents chose to be buried in the Hauge Cemetery outside of Deerfield, Wisconsin. We know that Ole and Malene Johnson were early members of the Scandinavian Methodist congregation in neighboring Cambridge (now called Willerup Methodist — see this post), but their choice of cemetery also suggests a tie to the Hauge Church. Haugean Lutheranism was a popular movement within Norway that gained momentum around the same time as mass migration to the U.S. (for more detail, see this article). Haugean Lutherans emphasized piety, thrift, and diligence, and they distanced themselves from the Norwegian State Church, whose formality they believed robbed people of authentic spiritual experiences. The first Norwegian Lutheran minister in the U.S. was a Haugean named Elling Eielsen, who founded a church — and later an entire synod — at the Jefferson Prairie Settlement (Rock County, Wisconsin) in 1846. Eielsen’s impact on the surrounding Norwegian-American settlements was profound (see this link). A Haugean congregation began in the Deerfield area during Albert and Julia’s childhoods. A church building was constructed in 1862 where the Hauge Cemetery exists today (Hwy 12 & 18), which was later relocated to downtown Deerfield. The man who married Albert and Julia in Nebraska, Ole E. Torgerson, was an ordained lay preacher from this congregation.

Bio of Rev. Torgerson from p. 602 in Rasmus Malmin and Olaf Morgan Norlie’s (1928) Who’s Who Among Pastors in all the Norwegian Lutheran Synods of America, 1843-1927. Minneapolis, MN. Augsburg Publishing House.

Photo of the Hauge Lutheran Church that used to stand outside Deerfield, WI near the intersection of Hwy 73 and Hwy 12&18 (source: Deerfield Historical Society). In 1894, the church was rolled into Deerfield on logs using a team of horses and stood at the corner of State and Bue streets. The congregation disbanded in 1917, and the church building was torn down in 1964. -

Notes from the heartland (Part 3: Texas)

Happy Rudesgiving!

I can’t remember when Rudesgiving originated, but with such a geographically dispersed family — and with each of my brothers having their own families and in-laws — we needed to come up with our own convenient time to gather. So, for several years we’ve been finding an off-peak weekend to meet up. This year it’s my brother Sam and his family in Texas who are hosting.

Happy Rudesgiving! But our careful planning was no match for a government shutdown and its effects on air travel. My brother Wayne and his family decided to stay put, rather than risk not getting home in time for an important event, and so sadly they are missing from the photo above.

The home of the Texan Rudes is warm and inviting, and we’ve spent the day eating good food, talking, and playing games. What really makes it feel like a family holiday gathering for me is the coming together of multiple generations under one roof. I don’t get this experience in my daily life, and it’s this missing ingredient that’s so reminiscent of my childhood.

Thanksgivings and Christmases in my youth typically involved driving the five hours from Indiana to my grandparents’ farmhouse in Wisconsin. There we would crowd into the living or dining room with dozens of other relatives and find ourselves picking up conversations we had misplaced months ago. The heat emanating from the kitchen was compounded by the heat of too many bodies in a small space. The sounds of aunties cackling, unsupervised children, whining dogs, clanking plates. Yes, it was a little chaotic, but for me it was heaven.

My mom won’t approve of me writing this, but on her side of the family, chaos was a feature, not a bug, of the holiday programming. It was expected and to some degree I think appreciated. Yes, it could test your patience, but it was also a sign of life. My mom claims that the large family gatherings hosted by her grandparents a generation earlier were a more staid and formal affair, where children were to be seen and not heard. But I’m unconvinced. This photo from Thanksgiving 1953 has a hint of the chaos that I’m talking about.

Thanksgiving 1953, home of Jessie & Albert Reiner (Pebble Brook Farm), Cambridge, Wisconsin. From left: Roger Reiner, Beverly Smith (on Roger’s lap), Glenn Smith, Ruthie Reiner, Bobby Nitsch (on Ruthie’s lap), Kathleen Reiner, Janice Quam, Gary Smith (on Jessie’s lap), Jessie Reiner, David Reed (on Jessie’s lap), Joyce Reiner, Charleen Quam, Sandy Quam (on Charleen’s lap) Family gatherings in my dad’s childhood were convivial but maybe slightly restrained, at least compared to today. Grandma Borghild would bring out her best china and children were to mind their manners. You might get a shirt three sizes too small for Christmas, but you needed to thank Grandma anyway.

My dad — at left are his sisters and two cousins. Grandma Borghild Rude in the background.

Back: John Rude, Bob Rude, Russell and Evelyn Hexom (holding Gloria), Jean Rude, Borghild Rude

Front: Cathe Rude, Alan Hexom, Marilyn Rude, and Dennis RudeChristmas 1959, home of John and Borghild Rude, Christiana Township, Dane County, Wisconsin (Photos courtesy of Carol Rude Luiso) For today’s festivities in Fort Worth, the multigenerational aspect was on full display when we played “Hitster”. This game requires you to place the songs you pull from a deck into their proper chronological order. My parents were experts in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. My generation did pretty well with the 80s, 90s and early 2000s. And my niece excelled at the 2020s. It struck me that where we all failed was in the late 2000s and 2010s. I suspect that’s where my younger brother Wayne and his fiancée would have put us to shame, had they been with us. Clearly, a rematch is in order!

We dined on award-winning chicken and dumplings…

And my niece’s homemade triple chocolate cake!

Spence and Peggy Sue relax on the rug

My dad gifted my brother and niece a tackle box full of lures

Bathroom decor, courtesy of my niece -

Notes from the heartland (Part 1: Iowa)

I’m on a kind of pilgrimage through America’s heartland with my trusty companion, my six-year-old Golden Doodle, Spence. This isn’t your average road trip; we’ll be traveling through time as well as space. We have a destination — my brother’s home in Fort Worth, Texas for our family’s off-schedule Thanksgiving (what we call Rudesgiving) — but the destination is only part of the story.

Taking a little break in Dows, Iowa to throw the squeaky ball It is good to have an end to journey towards; but it is the journey that matters, in the end. — Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

In studying my family’s history, I’ve been especially interested in the migration stories. My branch of the family is unusual in the sense that my direct ancestors, by and large, stayed put after initially settling in southern Wisconsin. But this wasn’t always the case for my settler ancestors’ siblings, many of whom fanned out across the expanse of the North American continent. For these family members, the Atlantic crossing was merely the first in a series of migrations.

Alleman, Iowa

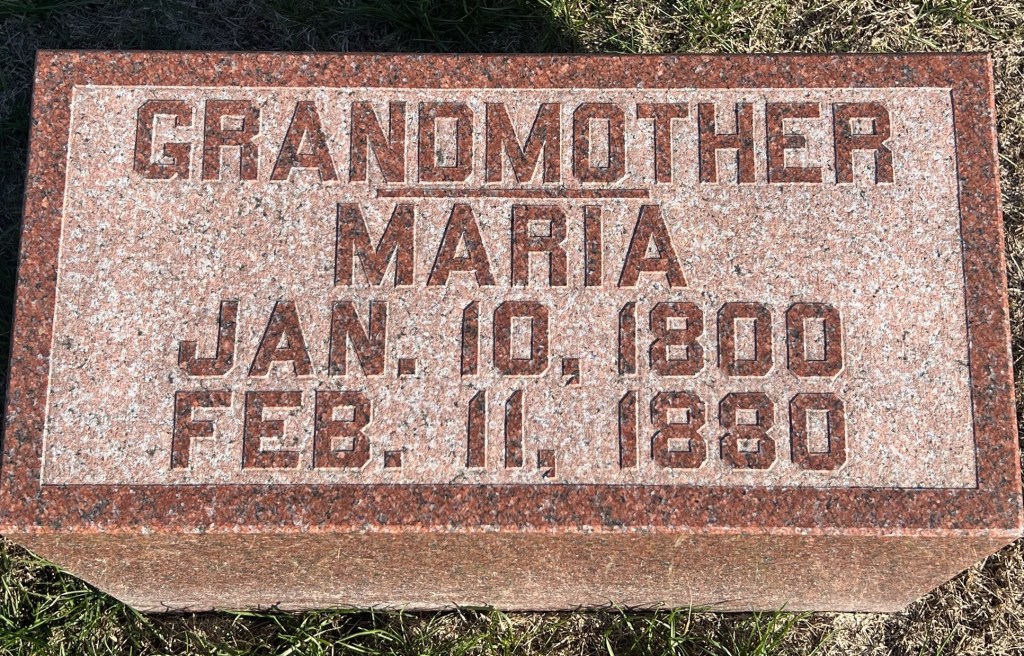

Our first stop on this trip is a rural community called Alleman, located a few miles north of Des Moines, Iowa. Home to only about 400 residents, Alleman is the kind of town you could easily drive past without noticing. But it’s the final resting place of one of my direct ancestors, my 4x great-grandmother, Maria Tontz Hitz, and so we’ll pause here to pay a visit.

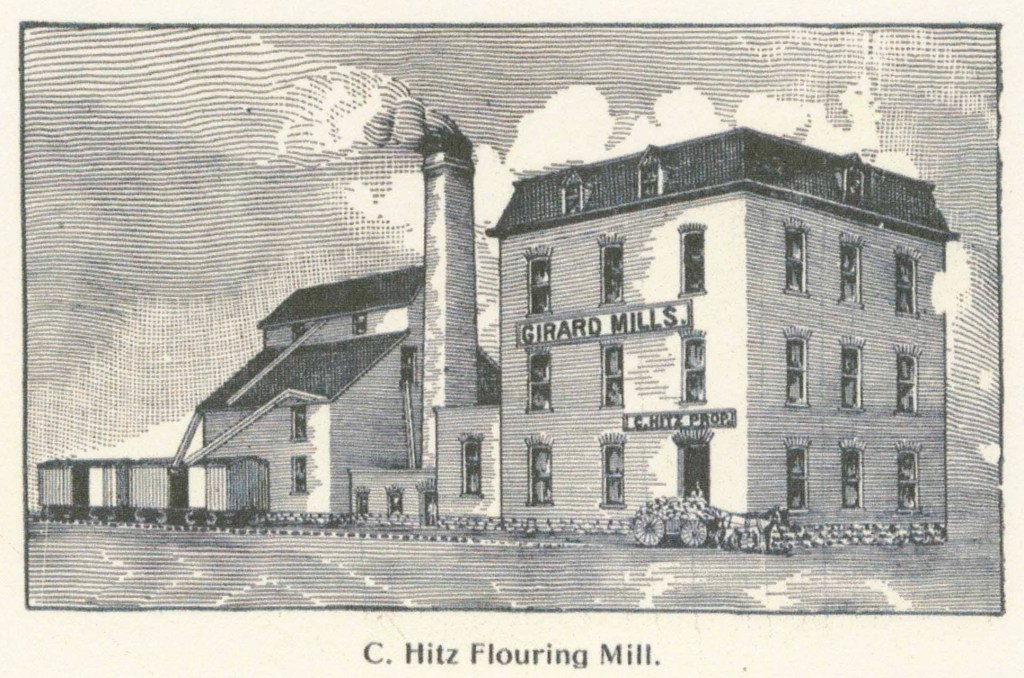

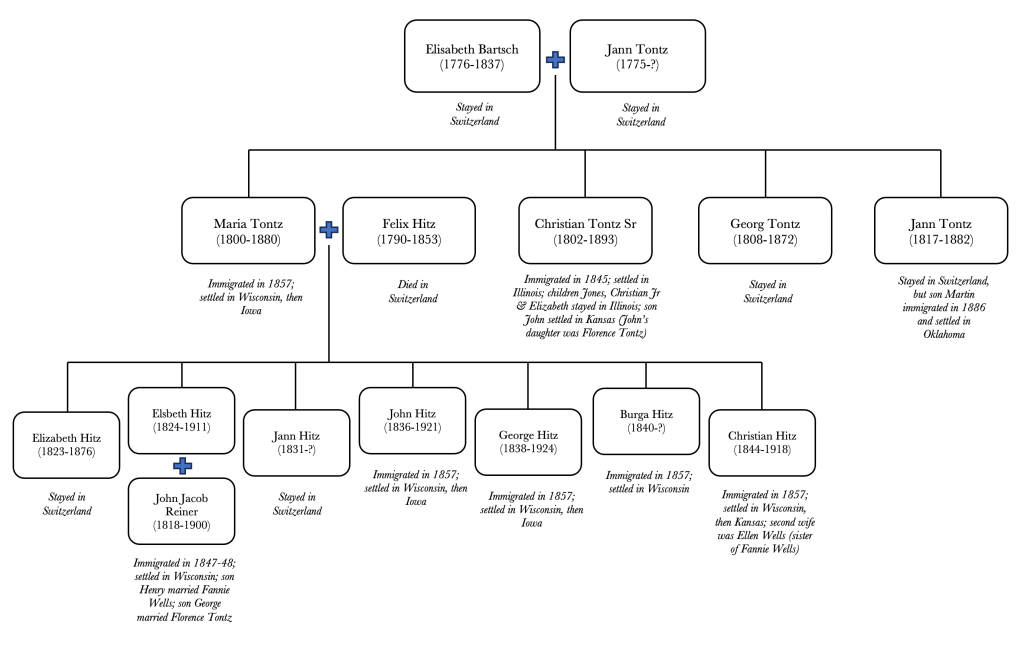

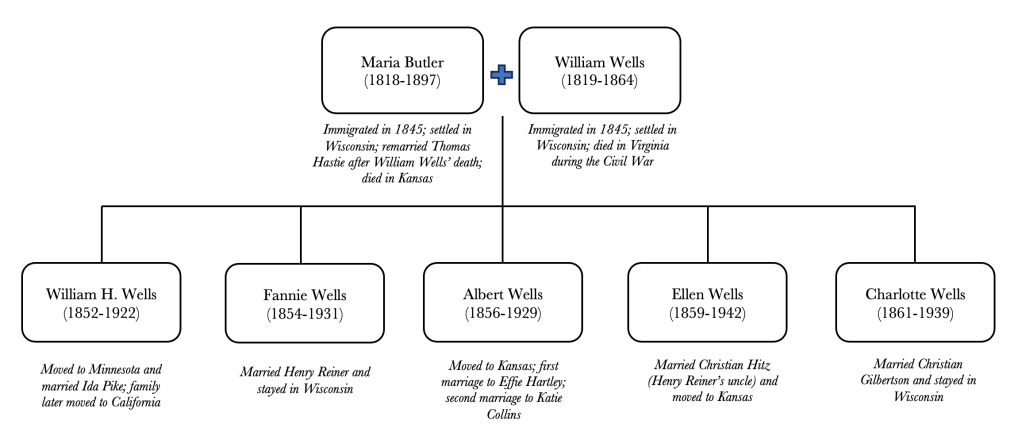

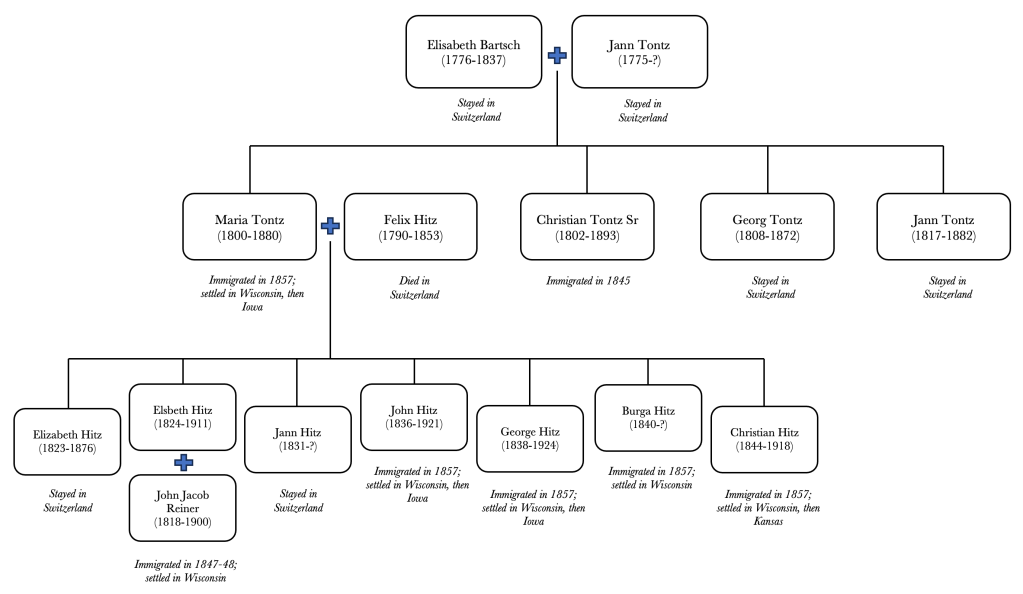

Alleman, Iowa Maria Tontz was born in Seewis im Prättigau, a small village in the Davos/Prättigau region of Switzerland in 1800. In 1857, four years after her husband Felix Hitz’s death, Maria sailed from Le Havre, France to New York with three of her adult children: John (Hans), George, and Burga. Her son Christian had arrived two years earlier, and her daughter Elsbeth (my 3x great-grandmother) had arrived in 1848 to join her fiancé, Johann Jacob Reiner. The entire family settled in or near Madison, Wisconsin — the small capital of the newly minted state. Maria lived with her sons John and George on a farm in the town of Burke, just east of Madison.

My Swiss roots – the Tontz / Hitz family tree. I am descended from Elsbeth Hitz Reiner, sister of John and George Hitz (see Chart C on this page). The Civil War swept the Hitz family up like it did so many families of the era. Two of Maria’s sons, Christian and George, enlisted in the Union Army, and fortunately both of them made it home. After the war, Christian headed to Kansas (more on his journey later), while John, George and their families headed to Iowa. Maria migrated to Iowa with her sons around 1870 and lived there until her death in 1880.

Hitz family plot, Lincoln Cemetery near Alleman, Iowa

Grave marker for Maria Tontz Hitz The Hitz brothers most likely moved to Iowa in order secure cheaper land. The Homestead Act of 1862 opened up vast tracts of farmland west of the Mississippi River, which homesteaders could claim if they paid a fee and made improvements to the land. Indeed, a 1937 letter written by Elizabeth Reiner Reinking (niece of John/Hans and George Hitz) notes the price: “They lived on my father’s farm for several years before moving to Alleman, Iowa where he (Hans) bought a farm at $2.50 an acre. This was in Civil War times and later became so valuable.”*

Grave markers of John and George Hitz; note George’s veteran marker

1902 plat map of Lincoln Township in Polk County, Iowa. Farmland owned by John Hitz can be found in sections 20, 21 and 28. (Source:

https://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/node/100697)

The farm once owned by John Hitz appears to still be a working farm. The house and outbuildings look recently rebuilt. Both John and George ended up having large families, and many of their descendants are undoubtedly living in the area today. It would be fun to meet some of them one day, but now it’s time for Spence and me to get back on the road.

View from the old Hitz farm

* Much of what we know about this branch of the family comes from the hard work of my great-aunt, Helen Reiner Reed, who conducted extensive archival research and preserved many family documents, such as the letters of her great-aunt, Elizabeth Reiner Reinking (1854-1945). The excerpt quoted here is found on page 30 of Aunt Helen’s genealogy, Ancestors and Descendants of Johann Jacob Reiner and Elsbeth Hitz and Allied Lines, published in 1984.

-

Center of the world

My dog Spence and I journeyed to the center of the world on Wednesday. We’re back, and we thought we’d tell you a little about it.

Spence took the opportunity to sneak a kiss while we posed for a selfie at the bdote (Pike Island) Minnesota’s indigenous people have passed down a variety of creation stories. Several of these speak of humankind’s origins at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. This land has thus been held sacred by the Dakota and the larger Oceti Ṡakowiŋ (aka Seven Council Fires or “Great Sioux Nation”). As described on the website of the Minnesota Historical Society,

“…the spirits of the people came down from Caŋku Wanaġi, ‘the spirit road,’ made up of the stars of the Milky Way, and when they arrived on Earth, the Creator shaped the first people from the clay of Maka Ina, ‘Mother Earth’ at Bdote. The people were the Oceti Ṡakowiŋ, a society that reflects their cosmic origin.“

A map of the area courtesy of https://bdotememorymap.org/memory-map/ The bdote (“confluence” in the Dakota language) was not only sacred but strategic. The colonizing forces from the East Coast understood that anyone who controlled this area controlled the Upper Mississippi and the valuable fur trade within it. More than any other Europeans, the French successfully penetrated the North American interior and forged lasting alliances with the native peoples. They dominated the region’s fur trade for the better part of three centuries, starting in the early 1500s. This dominance ended with the French surrender to the British at Montréal in 1760 – coincidentally, 265 years ago today. Had Montréal not fallen, maybe I’d be writing this post in French.

Cool map of the key players in 1754, created by “Zed3811” (source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1754_French_and_Indian_War.png). Note that the bdote is located in that dot of dark blue to the northwest of the “S” in Sauk and Fox. The British took over the French fur trade in the Great Lakes region, but they never fully secured the Upper Mississippi. Under the Hudson’s Bay Company, they did brisk business in the area through the early 1800s, much to the chagrin of the newly formed United States. The U.S. had its own booming fur trade, and after wresting their independence from Britain in 1783, Americans laid claim to all lands south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi. And then in 1803 the U.S. negotiated with France to gain rights over the vast plains west of the Mississippi – the Louisiana Purchase.

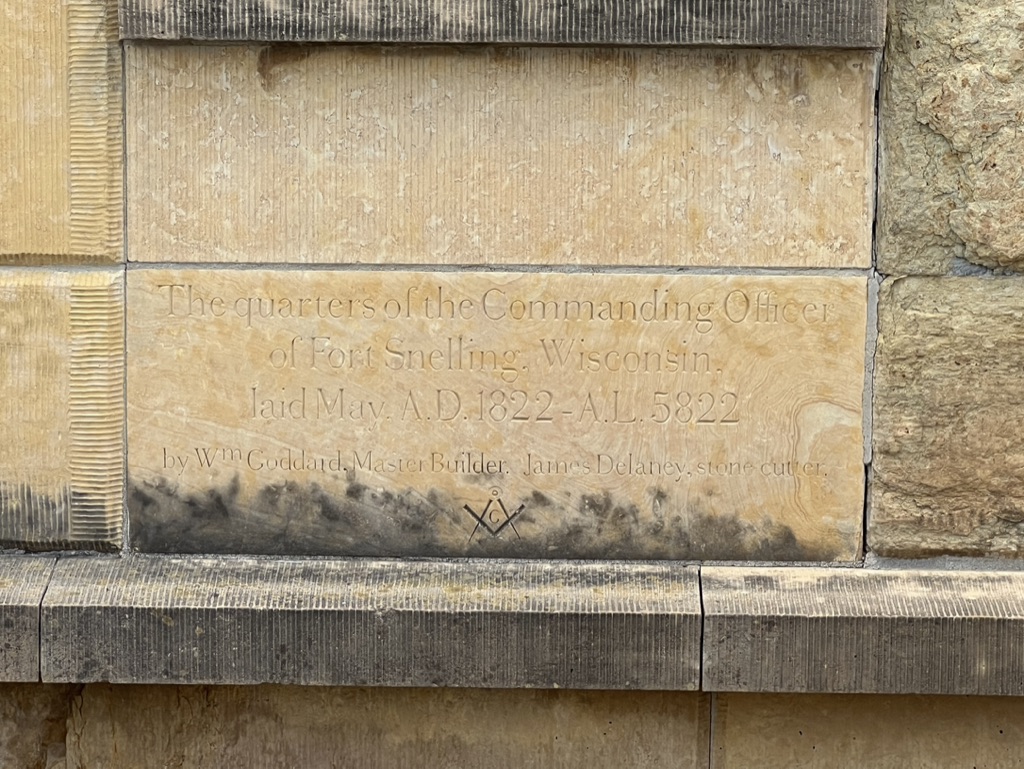

An 1814 map of the Louisiana purchase, courtesy of the Library of Congress (source: https://lccn.loc.gov/2001620467) But in practice, “Louisiana” was neither French nor British nor Spanish nor American. It was controlled by dozens of native nations, who had ceded nothing in 1803. The U.S. government, through its representative Lt. Zebulon Pike, made a shady treaty with the Dakota people in 1805 to secure land at the confluence of the Minnesota / St. Peter’s and Mississippi rivers and build a fort there. But a fort wasn’t built at the bdote until the 1820s. Both U.S. and British authority in the region was tenuous at best throughout the early 1800s. The situation almost ensured conflict.

British sketch of the fort at Prairie du Chien (source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM42230) The struggle between Britain and the U.S. for regional supremacy came to a head at the 1814 Battle of Prairie du Chien, a little-known chapter in the War of 1812. Under the command of Missouri Territory Governor William Clark (yes, that William Clark), the Americans hastily built a fort near the old French trading post of Prairie du Chien, situated at the confluence of the Mississippi and Wisconsin rivers. The Wisconsin River was a key artery in those days because it linked the Mississippi with the Great Lakes (via a portage to the Fox River), and thus the Atlantic. Unfortunately for the Americans, the fort at Prairie du Chien was captured by the British and their Ho-Chunk and Menominee allies a mere month after it was built. The British handed it back to the Americans once the war concluded in 1815, but first they gave it the same treatment they gave the White House: they burnt it to the ground. Had the war wrapped up slightly differently, the Upper Mississippi might have been included in Canada.

Anxious to secure the new territory, the Americans finally built their fort at the bdote in 1822. Sadly for Spence and me, dogs can’t take the tour at the fort, so I came back without him the next day.

Named after its first commander, Fort Snelling is situated on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the rivers below. In a strictly militaristic sense, Fort Snelling never saw “action”. A third conflict with Great Britain never came and no battles of the Civil War were waged in this region. Even during America’s wars with native peoples, Snelling wasn’t attacked. But the fort has borne witness to American history in other ways.

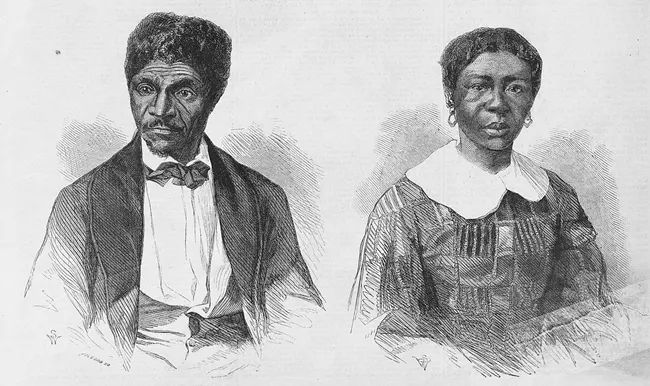

Dred and Harriet Scott (image courtesy of the National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/jeff/planyourvisit/dredscott.htm) For instance, in 1837 a U.S. Army doctor by the name of John Emerson came to reside at Snelling with an enslaved man he had purchased in Missouri — Dred Scott. There Mr. Scott fell in love with and married Harriet Robinson, an enslaved servant of Fort Snelling’s Indian agent, Lawrence Taliaferro. Taliaferro, acting as justice of the peace, performed the marriage himself and allowed Mrs. Scott to be transferred to Emerson. Emerson got assigned to various posts in the Midwest and brought the Scotts with him. After Emerson’s death, the Scotts tried to buy their freedom from his widow. When she refused, they sued for their freedom, claiming that they had been held illegally in non-slave states and territories (Fort Snelling was, at this time, in Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal.) The case went all the way to the Supreme Court and the Scotts’ legal defeat further flamed the tensions in the lead up to the Civil War.

The concentration camp at Fort Snelling (late 1862 or early 1863), source: https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/us-dakota-war During the Civil War, Fort Snelling was an important site for Minnesota soldiers to be recruited and trained. Some 25,000 soldiers passed through the fort during the war. Meanwhile, in the war’s second year, Minnesota’s Dakota people faced starvation due to their treatment at the hands of American settlers and the broken promises of Indian agents. A faction rebelled, killing five white settlers and kicking off a series of conflicts known as the Dakota War. U.S. Army regiments put down the rebellion and rounded up hundreds of combatants. Over 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death and 38 were hanged at Mankato after short and unfair trials. Over 1,600 non-combatant Dakota people were forced into a concentration camp set up at Fort Snelling. In the conflict’s aftermath, almost all Dakotas in Minnesota were exiled to far-flung reservations, as were 2,000 Ho-Chunk people who had not participated in the war.

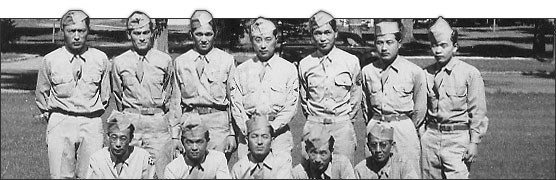

Photo of Ho-Chunk leaders, probably taken at Fort Snelling, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society (source: https://www3.mnhs.org/mnopedia/search/index/event/ho-chunk-and-blue-earth-1855-1863) Snelling continued to be an important military recruiting station for the next century of wars – the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II. As a former student of Japanese, I was fascinated to learn that Snelling was also the site of a Japanese language academy during the Second World War. The Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) trained over 6,000 men and women of Japanese ancestry in language skills that would help the U.S. armed forces decipher Japanese communications. They played a key role in Japan’s defeat. It’s a sad irony that most of these vital contributors were recruited out of the interment camps that the U.S. government had forced Japanese Americans into during the War.

Image of MISLS attendees, courtesy of the National Park Service (source: https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/historyculture/langschool.htm) Spence and I had come to walk the bdote, the confluence of rivers. What we discovered was a confluence of histories, some proud and some painful, and a true center of the world.

Pike Island is quiet and beautiful, and probably a much easier hike than Pike’s Peak

Where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers meet, the bdote at Pike Island

View of the bdote from Fort Snelling -

Glimmers from a golden age

Norway is one of those countries – like Macedonia or Mongolia – that has a modest footprint today but once settled and ruled distant lands. This is not to say that Norway’s best days are behind it. But it does have a storied, almost mythic past. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the Old Kingdom of Norway did not leave behind much in the way of monumental architecture. Much of what was built was made of wood, and wood doesn’t tend to stick around.

But now and again in Norway you’ll come across a relic from this bygone era.

Borgund Stavkirke

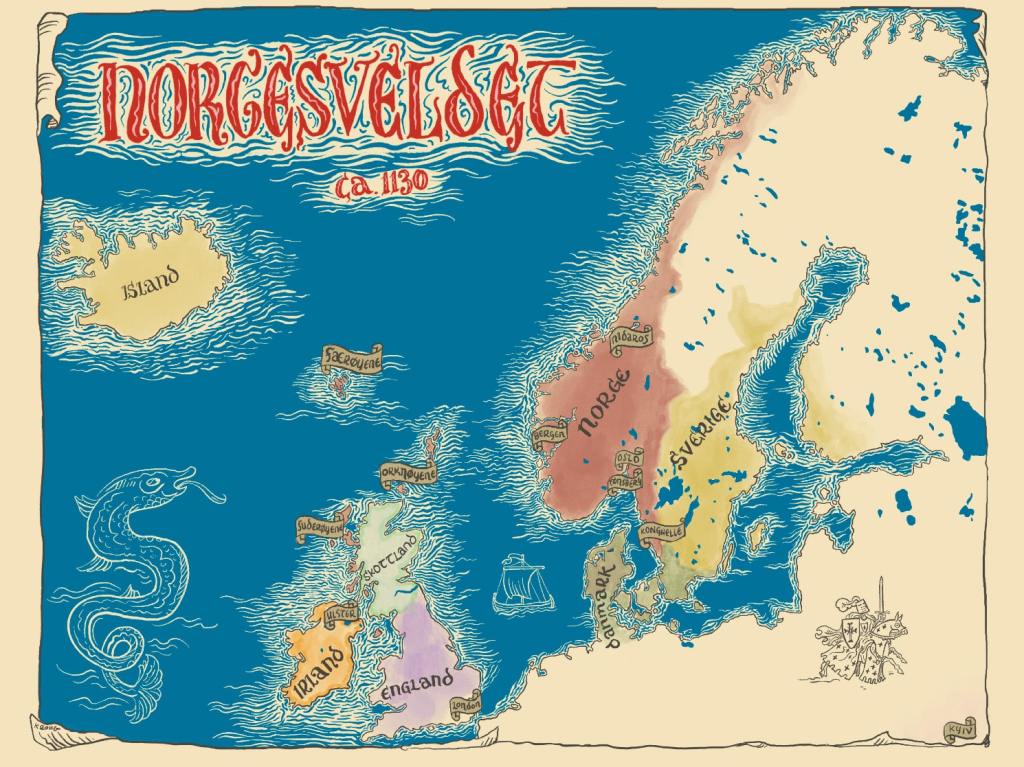

The carvings at Borgund evoke Viking stonework. I had the opportunity to see Borgund on May 9th, a bright afternoon. But stepping inside, it was surprisingly dark. When Borgund Stave Church was built, circa 1200, Norway was going through a period of intense civil war — internal conflicts that didn’t end until about 1240. The kingdom’s holdings at that point stretched from Båhuslen in the southeast (now part of Sweden) to Iceland and Greenland in northwest. In between, the Kingdom of Norway ruled parts of Ireland and Scotland, as well as the Isle of Man, Orkney, Shetland, the Hebrides and the Faroes.

Illustration by Kristian Krohg-Sørensen (downloaded from the Norwegian National Library website) Central to the administration of this expansive kingdom was the Norwegian Church. Norway was becoming Christian in exactly the years when it acquired overseas territories (between about 1000 and 1150). Despite the kingdom’s strong association with Christianity, elements of pre-Christian style shine through in those early churches.

Prior to the Black Death in 1349, there were over 1,000 stave churches in Norway. Today only 28 are still standing (see www.stavechurch.com).

Lomen Stave Church, built around 1192. Just a drive-by photo op on my journey east (May 9th).

Garmo Stave Church, built around 1150, disassembled in 1882, and rebuilt at Maihaugen in Lillehammer in 1921. I visited this church with my relative Mathilde Hanssen on May 14th. The Black Death was the beginning of the end of Norway’s “golden age.” In less than 50 years, Norway was absorbed within the Kalmar Union. The country’s population didn’t recover for another 300 years, by which point Norway was a jewel in Denmark’s crown. That diminished population could not sustain all those churches, and many were demolished. Several stave churches that remained intact during those years were later razed during the Reformation (post-1537).

The old stone churches of the early Middle Ages fared much better. There are over 150 stone churches from that era still standing in Norway, most of which were built between 1150 and 1250. On May 10th, I had the opportunity to visit one of them — Balke Church in Østre Toten, where my great-grandma Borghild Helgestad was baptized.

Balke was built high on a hill so that parishioners could hear its bells for miles around. The construction combines elements of Romanesque and Gothic styles. The semi-circular apse with half-domed vault was difficult to build at that time and, according to Mr. Øksne, speaks to the importance of the parish.

Entrance

Hilde, Mr. Øksne & I

Mathilde & Hilde

Altarpiece (central panel)

This baptismal font was used here since 1719

The magnificent altarpiece was consecrated in 1526

Mr. Øksne points out the altar

Balke is a two-walled structure with filling (1.5 meters thick) Mr. Roar Øksne, the former verger, was kind enough to give me and two of my local relatives (Hilde Iversbakken and Mathilde Hanssen) a detailed tour of this impressive structure. Mr. Øksne explained that Balke was probably built around 1170 but underwent major renovations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

He painted a vivid picture for us of what people experienced when they walked into the church in the Middle Ages. The windows were even smaller than they are today, making the interior dark. The parishioners had to stand during services, huddled together in the unheated building, and their participation in the service was minimal. In those days, Mr. Øksne explained, a church service focused more on the rituals between the priest and God — the congregation were mere witnesses to the event.

I wonder if this was true in all of Christendom, or if this was a holdover from how earlier generations of Scandinavians worshiped. I visited the University of Bergen Museum on May 21st, and a display there highlights how the image of Christ changed during the early Middle Ages in Norway. Three crucifixes are juxtaposed: the one at left from about 1150, the one at right from about 1275, and the one at back from about 1330.

The oldest of these, explained a guide named Thomas, is looking straight at you. The people of that time would never accept a God who bowed his head. He needed to be a strong leader you could follow into battle. He suffers but faces death with eyes wide open.

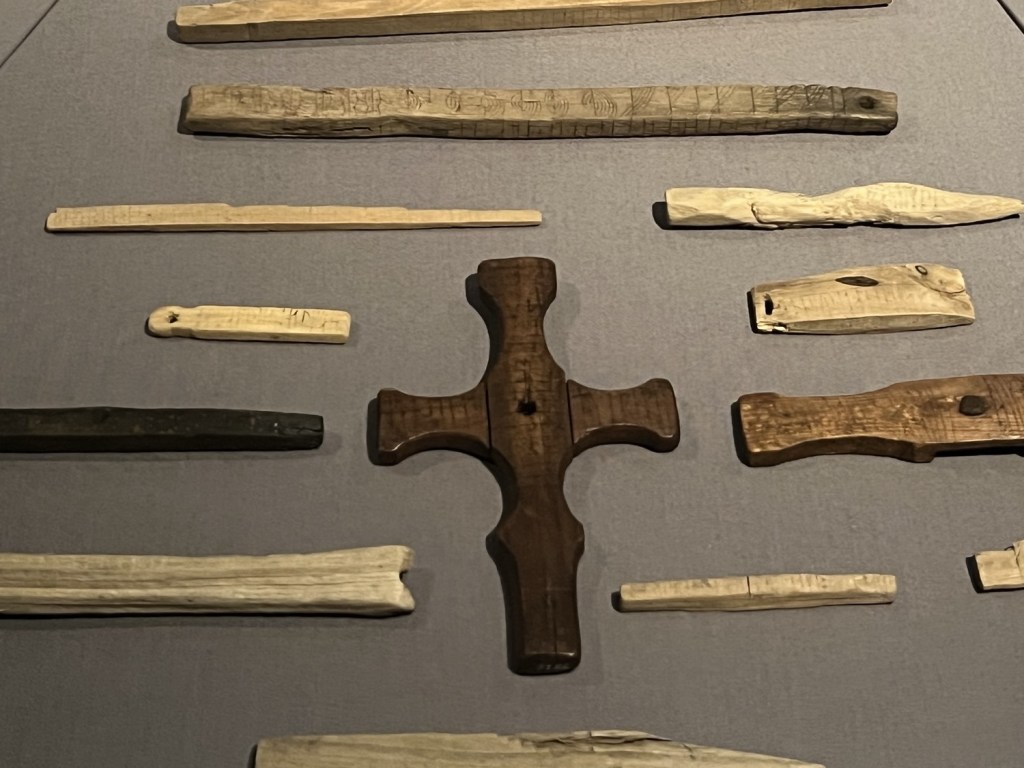

Relic shrine from the Church of St. Thomas in Filefjell, ca. 1230-1250, University of Bergen Museum. This piece blends classic Norse elements with images of Christ and his followers in Roman togas. And so it is, I suppose, in all times of cultural transition. We transmit new messages using the vocabulary of the past. This was true in a literal sense in the early Middle Ages, as the older runic writing system — believed to have been Odin’s reward for sacrificing himself — was used to convey Christian blessings and prayers.

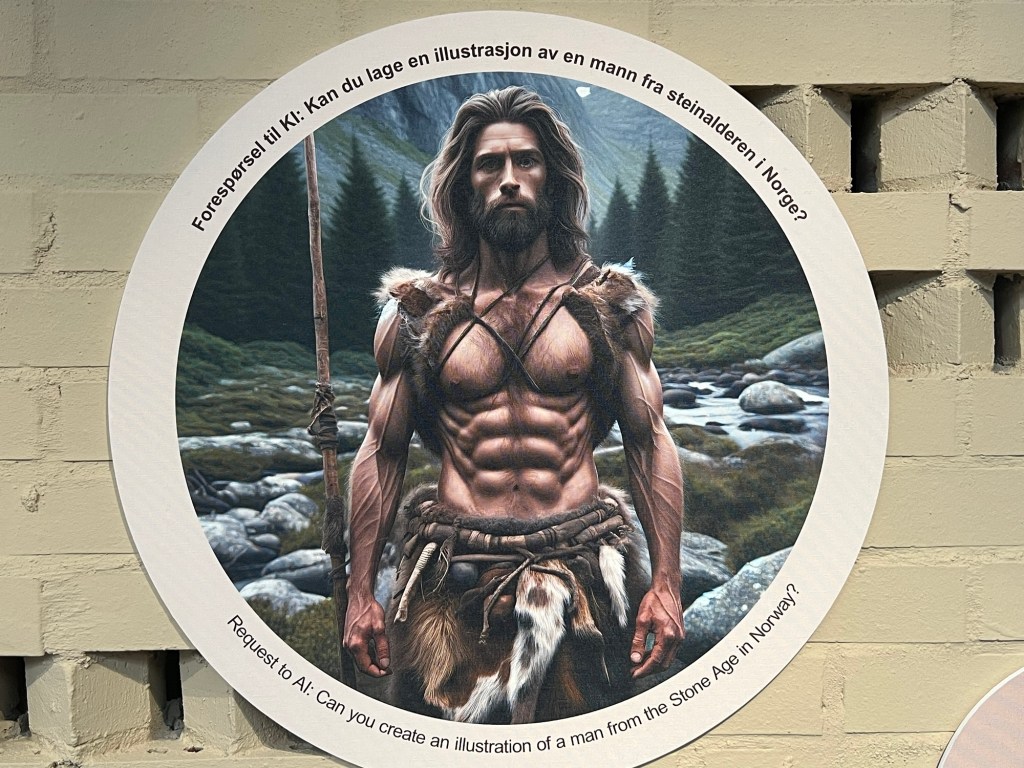

A photo from my visit to the Bryggens Museum in Bergen on May 22nd. This museum houses the largest collection of runic inscriptions in the world. All of the inscriptions in the photo above use the runic alphabet, although some are in Old Norse and some are in Latin. All pieces date from the 1100s, 1200s or early 1300s. When we interpret the past, we naturally use the vocabulary of the present to understand it. This “back translation” allows for clarity, but of course something is always lost in translation. Much of what we know about Viking Era history and religion, for example, comes from the sagas written down centuries later by the Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241).

A copy of the Sagas of the Kings, on display at the National Library in Oslo (photo from my visit on May 15th) In Sturluson’s “histories”, the stories of historical figures blend with both Biblical and Norse legends. It can be hard to parse fact from fiction.

This morning (May 23rd) I had the chance to visit the National Museum of Iceland — a final stop before heading home. Here the 13th century is remembered differently: not as a “golden age” but as an era of subjugation under the Norwegian kings. It’s the period just prior — what we might call the Viking Era or what the Icelanders call the Age of Settlement — that is probably the most romanticized here.

Norse society’s transition in the early Middle Ages from pagan Viking to fully Christianized is particularly evident in Iceland. Unlike in Norway (and other lands), where those who failed to convert were put to death, Icelanders peacefully adopted Christianity through a democratic process. But they were allowed to worship as they desired in private.

A grave finding from 11th or 12th century Iceland. Is it Thor’s hammer? A Christian cross? Both? (National Museum of Iceland) Walking through a museum like this, I ponder how those who come after us will summarize our current times. What objects from today will find their way into future museums? Will the 21st century be seen as transitional as the 13th? Maybe they will marvel at how we embraced scientific ideas while still holding onto non-scientific beliefs — stumbling to fully face up to our prejudices, our social inequalities, and our impact on the environment. Only time will tell.

-

Bridges across the pond

To travel abroad as an American in 2025, particularly to Western Europe, is to open yourself up to questions about what it means to be an American. For 80 years, Europe knew it could rely on the U.S. as a bulwark against the forces of despotism and tyranny. That faith has been shattered.

Norway was one of 12 founding members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) when the alliance formed in 1949. But, given the actions and rhetoric of the Trump administration, Norway and other NATO members can’t assume that the U.S. would come to their aid if attacked. Trump has even gone so far as to threaten the sovereignty of the people of Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark.

Moreover, the Trump administration is imposing tariffs on many goods coming in from overseas, even goods from longstanding allies like Norway. The president seems determined to destroy the international goodwill that our nation has painstakingly built over decades.

As an individual American confronted with these realities, I’ve felt pretty powerless. I can’t right the wrongs my government is committing abroad. Nor can I explain its actions. Nor can I articulate why millions of my fellow Americans seem to support these actions.

I do, however, believe in the power of citizen diplomacy, and I’m hopeful that the various personal, professional, cultural and economic ties between the U.S. and Norway will serve as the foundation for a renewed friendship once the Trump administration is out of power.

So, in the conversations I’ve had during my travels these past two weeks, I’ve done my best to listen and understand, and I’ve tried to remember I may be one of the few Americans folks here have the chance speak to personally during these tumultuous years. These personal connections were the highlight of my trip.

I gave NATO tie tacks to a couple of the folks I met on this trip Here are a few glimpses of those conversations.

Ole Johan Hauge, local historian in Arna (near Bergen)

Arne Storlid, distant cousin on my mother’s mother’s mother’s side. Photo taken on the Hauge farm in Arna.

Ove Farsund, Erik Ole Haugen, and Judith Hegrenes of Førde (Sunnfjord); photo taken at Huldafossen

My relative Hilde Iversbakken and her children (living in Kapp) engaged me in several conversations about the current state of affairs in the U.S. In this photo, Hilde is serving up kjøttkaker (meatballs) while daughter Josefine takes a break from her studies. (These relatives are on my father’s father’s mother’s side.)

One of Hilde’s daughters, Mathilde Hansson, was an international studies major and now is focused on business. She’s a voracious consumer of news media and knows far more about U.S. politics than most Americans. Photo taken at Maihaugen in Lillehammer.

Cake, coffee and a heartfelt conversation in Gjøvik with the Lindalen family: Ole and Willy on the left, Gry on the right. (The Lindalens are relatives on my mother’s father’s mother’s side)

Stimulating conversations about business, international travel and politics with Kristian Harby, while we rode around Hamar in his 1967 Alfa Romeo. (Kristian is a relative on my father’s father’s father’s side.)

In Oslo, I got to meet Torstein Torblå, whom I had connected with via AncestryDNA. Our conversation ranged from WWII to the future of data consulting. (Torstein is a relative on my mother’s mother’s mother’s side.)

I was treated to a syttende mai dinner by the Kittelsen-Larsen-Greibesland families in Kristiansand (from left: Morten, Mats, Sina, Jesse, Kjell Inge, Linda, Reidar, Lilian, Henriette, Frida, Roger, and Alf). They are relatives on my mother’s father’s mother’s side.

My final meet-up on this journey: I caught up with an old friend from my NYC days, Snorri Sturluson, this evening in Reykjavik.

Street art in Stavanger

-

Norway’s scattered children (part 2)

One-third of Norway’s population left the country between 1825 and 1925 — nearly a million people. As a citizen of a country that has more often been the recipient of migrants, I can scarcely imagine the impact those departures would have had, both for individual families and for the nation as a whole. In a previous post I considered the Norwegian diaspora in the United States and those settlers’ assimilation into the American mainstream. In this post, I grapple with what that exodus has meant for those left behind and how modern Norwegians view their “cousins” across the pond.

Model of the first emigrant ship from Norway, the “Restauration”; on display at the Maritime Museum in Stavanger

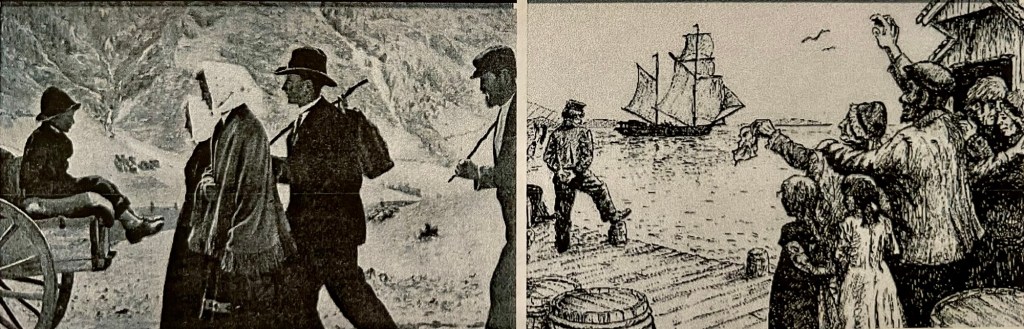

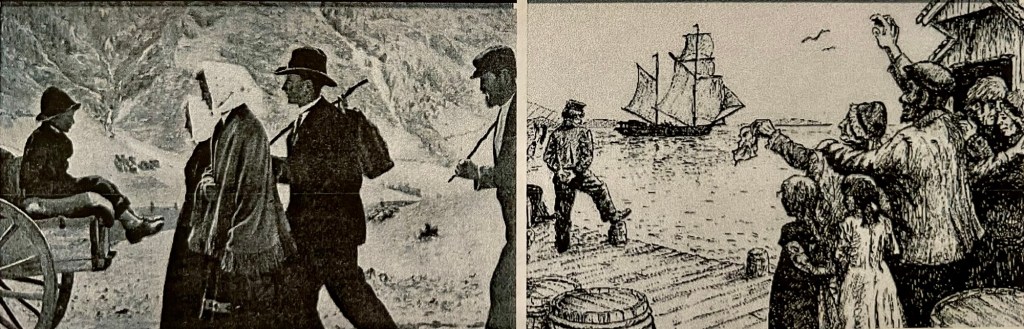

Images courtesy of Ole Johan Hauge, a local historian I met in Arna on May 7th Traveling around Norway in the last couple of weeks, I am struck by how often I’ve come across exhibits and events marking the 200th anniversary of the first emigrant ship to America. Individual communities around the country have planned a variety of lectures, activities and displays to commemorate this bicentennial. These programs are organized by local committees that roll up to a national initiative — Crossings.

Here is their website: https://utvandrermuseet.no/2025. In the States, we have a few such events as well, including a conference to be held in June at St. Olaf College in Minnesota. But the sheer scale of these activities in Norway highlights a key takeaway from my explorations: the emigration period had a massive impact on Norway and its view of the U.S. It looms large in Norway’s collective imagination.

When I was in Førde on May 8th, I had the privilege of participating in one of the projects associated with Crossings — an oral history project organized by a volunteer organization called Memoar. One of Memoar’s founders, the freelance journalist Bjørn Enes, interviewed me about the Norwegian diaspora and my family’s emigration experiences. Here’s a link to the website and a summary of the interview: https://www.memoar.no/mig/jesse-rude (The interview is a bit long, but if you are interested in watching it, send me a direct message and I’ll provide the password.)

And on May 15th, driving out of the Hamar area, I stopped by the museum that’s helping coordinate these events — Norsk utvandrermuseum (The Norwegian Emigrant Museum), located in Ottestad. The indoor exhibits are closed until next month, but you can walk around the grounds and see a collection of historical buildings relocated from Norwegian-American farms and communities — a little town on the prairie!

Multi-use building, built c. 1873, Kindred, ND

Barn, c. 1860, Highlandville, IA

Corn crib, c. 1858, Coon Valley, WI

Granary, 1870s, Highlandville, IA

Oak Ridge Lutheran Church, 1895, Houston, MN

Home, 1902, Highlandville, IA For anyone who grew up in the American Midwest, buildings like these look very familiar. I was interested to learn that new words — like kornkrybbe (corn crib) — entered the Norwegian lexicon through Norwegian Americans. Later that day, I took in an exhibit at the National Library in Oslo called “Rett vest. Drømmer om et bedre liv i Amerika” (Due west: Dreams of a better life in America). The exhibit stitches together the letters, stories, and even “tall tales” sent from emigrants back to their relatives and friends in Norway… dreams of what might be possible in a new land.

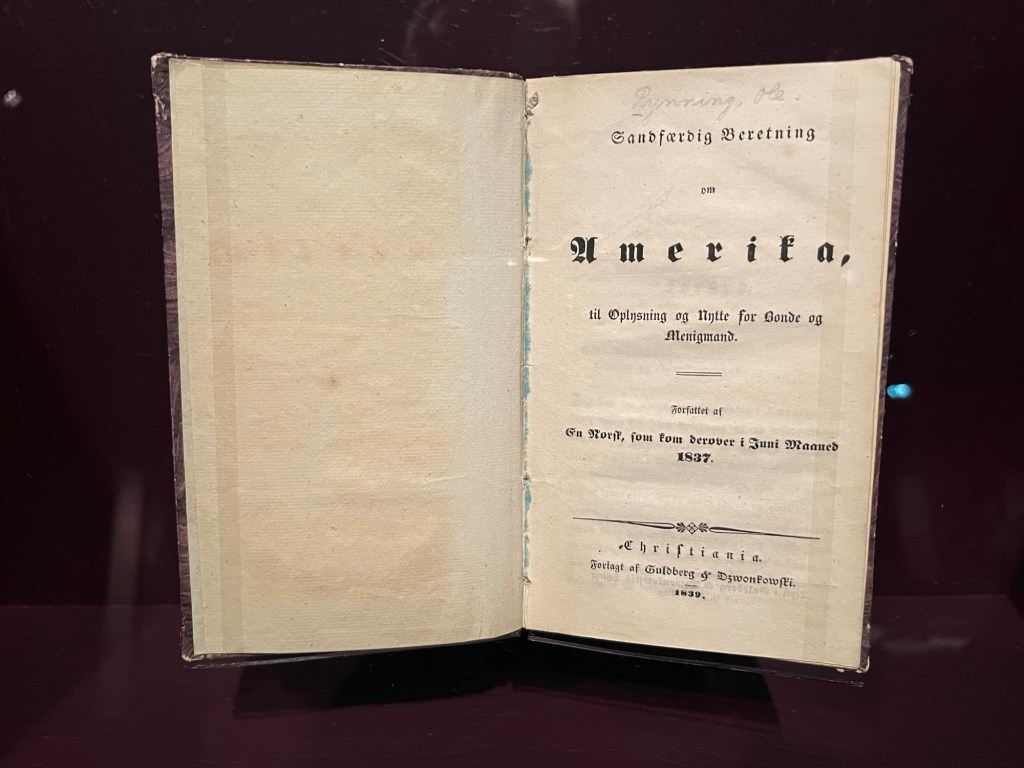

“America for Dummies” — In 1837 a Norwegian emigrant named Ole Rynning wrote a manual for folks back home interested in a life in the States. His manual inspired two ship-loads of migrants to set off for America, but by the time they got there Rynning was dead. The community where he lived was a malaria-infested swamp. One such dream, which I hadn’t been aware of, was the violinist Ole Bull’s aspiration of founding a Norwegian colony in Pennsylvania. In 1852, he purchased over 11,000 acres (45 square km) and attempted to establish four Norwegian communities in his “New Norway”. It was an epic failure. According to the exhibit, the failure of Bull’s grandiose vision may have inspired some satirical aspects of Henrik Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt.

The only map that has “Oleana” marked — one of the communities in Ole Bull’s “New Norway” which he named after himself The materials from the exhibit point to a central theme I’ve picked up on here in Norway when discussing the diaspora — a fascination with America, tempered by a healthy skepticism of its endless bounty and so-called freedoms.

Let’s address the “endless bounty” first. One of the branches of my Norwegian family left in 1904, just a year before Norway’s independence from Sweden. According to my great aunt Carol, this branch lost touch with relatives in Norway after my great-great grandmother Sophia’s brother Hans Hanson died in Milwaukee in 1927. The siblings back in Norway believed that they should have inherited more from his estate since “Americans are so wealthy”. The reality, however, was that Hans and the rest of the family in the States weren’t wealthy; they were scraping by as best they could.

I am happy to report that, 98 years later, these relations are well and truly mended.

Making pizza with Iversbakken-Hanssen family in Kapp, Innlandet (from left: Raimond, Mathilde, Josefine, and Hilde) Last week, I stayed with Hilde Iversbakken and her family — the descendants of my great-great grandma Sophia’s sister Johanne. This family took such great care of me. In addition to wonderful meals and outings together, I had the privilege of hearing about their impressions of the States and the American people. Norwegian media is fairly saturated with American TV and movies, but a driving trip Hilde and her family took in 2023 changed the way they saw America. They drove from New York to Wisconsin and back again, traversing southern Canada, Detroit, Chicago, Washington D.C., Philadelphia and all points in between. They took the time to get to know the “real America”, and they’re glad they did.

Engaging in these conversations, I felt that my Norwegian relatives could see my country more clearly, more objectively than I could myself. While they were extremely complimentary of all those they met — particularly their relatives in Wisconsin — their perspective as Norwegians helped them see some of the contradictions inherent in American society, contradictions that are hard for us Americans to look at head on. I feel greatly enriched by these exchanges.

A photo from Hilde’s family’s visit to Wisconsin in 2023; cemetery at East Koshkonong Lutheran Church (from left: Kathinka, Josefine, Raimond, Mathilde, Hilde, and Kristian) A topic that came up several times in one form or another was the concept of freedom and the role of the state. In Norway, it is the government that offers individuals freedom: freedom from worry about healthcare, education and other basic needs, freedom to pursue a life not constantly concerned with making ends meet. Whereas in the U.S., the government is often viewed as the enemy of freedom. Freedom to many Americans means freedom from the government.

Similarly, my family in southern Norway who generously hosted me during the 17th of May celebrations, expressed bafflement over America’s relatively loose laws on the possession of alcohol, fireworks, and most of all, guns. Likewise to the unfettered use of large trucks, recreational vehicles, and fossil fuels. Such “freedoms”, where do they lead? To the loss of the life… the loss of freedom. Why don’t Americans see this?

A pre-17th of May grill with the Kittelsen and Larsen families of Øvrebø, Agder (from left: Linda, Henriette, Frida, Roger, Kjell Inge, Morten and I)

17th of May festivities with the Kittelsen and Larsen families (from left: Linda, Henriette, Roger, Jesse, Morten, and Kjell Inge)

Experiencing “friluftsliv” (outdoor life) with my relatives in Agder on May 18th — just a little 30 km bike ride to work off the cake we ate on syttende mai (from left: Kjell Inge, Roger, and Alf) One of my relatives paraphrased a Norwegian commentator: “Great freedom requires great responsibility. Without responsibility, freedom is egoism.” I thought this was insightful and underscored the difference in each society’s approach to the concept. Norwegians generally trust their government to provide reasonable boundaries within which they can enjoy their freedoms. For many Americans, however, that trust is greatly eroded, and for those who lack trust in the government any such responsibilities get labeled as roadblocks to their freedom.

The gulf between Norwegian Americans’ and Norwegians’ political views is larger than is typically admitted. Many of us in Minnesota, for instance, like to think we’re running our state in a more Scandinavian style. But while our state taxes may be a little higher and our welfare a little more generous than our neighbors’, I just don’t see the kind of collectivist ethos that exists in Norway.

Somewhere along the way — perhaps especially during the Second World War — Norwegians learned that if they don’t stick together and trust one another, they won’t survive. But I wonder if Norwegian Americans, like Americans more generally, took away the opposite lesson — perhaps from decades of living in the low-trust environment of the western frontier. The American ethos is more along the lines of: if we don’t look out for ourselves, no one will. Despite Norway and America’s many cultural and historical links, this difference is as wide as the Atlantic itself.

***

Am I overgeneralizing? Have a different perspective? I would love to hear it. Please add your thoughts to the comment section!

Øvrebø, Bjørn Enes, Crossings, emigration, Førde, freedom, Greibesland, Hansen, immigration, Memoar, Minnesota, musing, nasjonalbiblioteket, Norsk utvandrermuseum, Norway, Norwegian history, Norwegian National Library, politics, Restauration, St. Olaf College, Stavanger Maritime Museum, U.S. history, utvandring

Deep Roots

Reflections on family history, identity and geography

Home

Welcome! I’ve created this site to share family history and collective memories.