-

Bertha Thorpe Veum and her family from Nes

As I mentioned in a prior post, my biological great-great grandfather, Erik Veum (1864-1942), made a journey back to Norway in 1921 with two of his daughters. Erik’s wife Bertha (1864-1937) did not accompany them. Perhaps she had less reason to travel. Unlike Erik, who had left many family members behind when he emigrated, Bertha brought Norway with her.

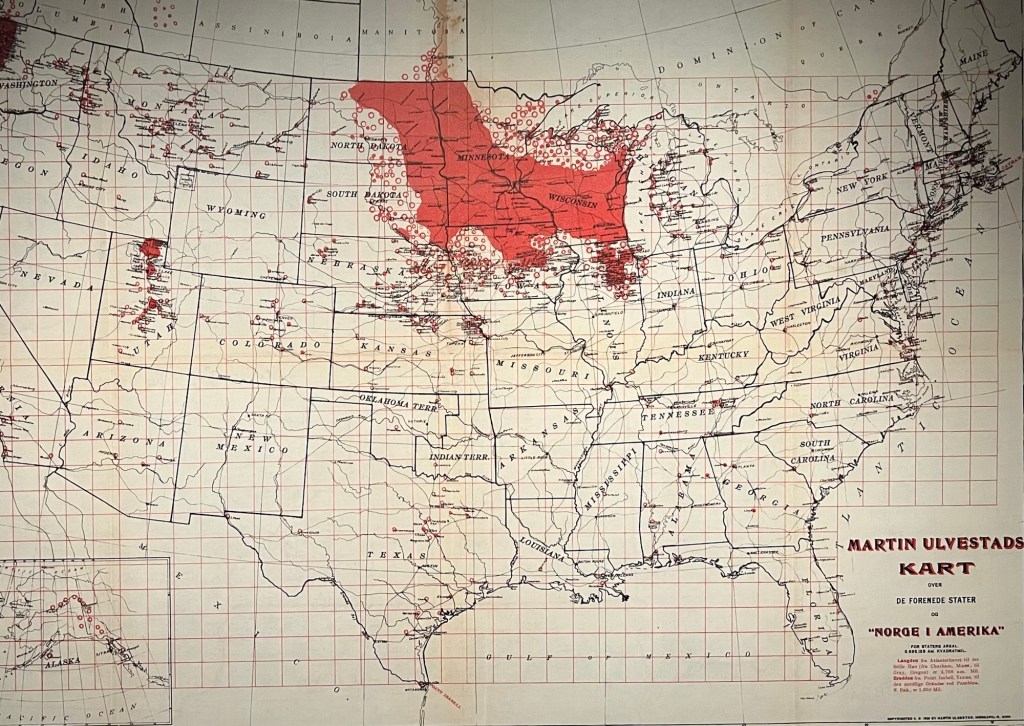

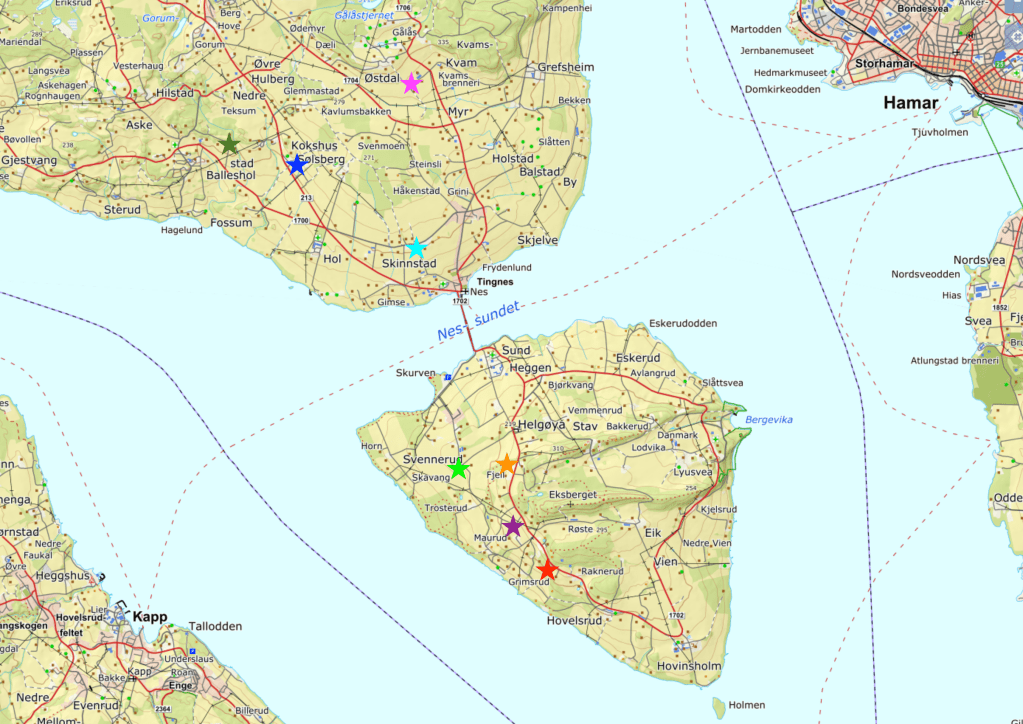

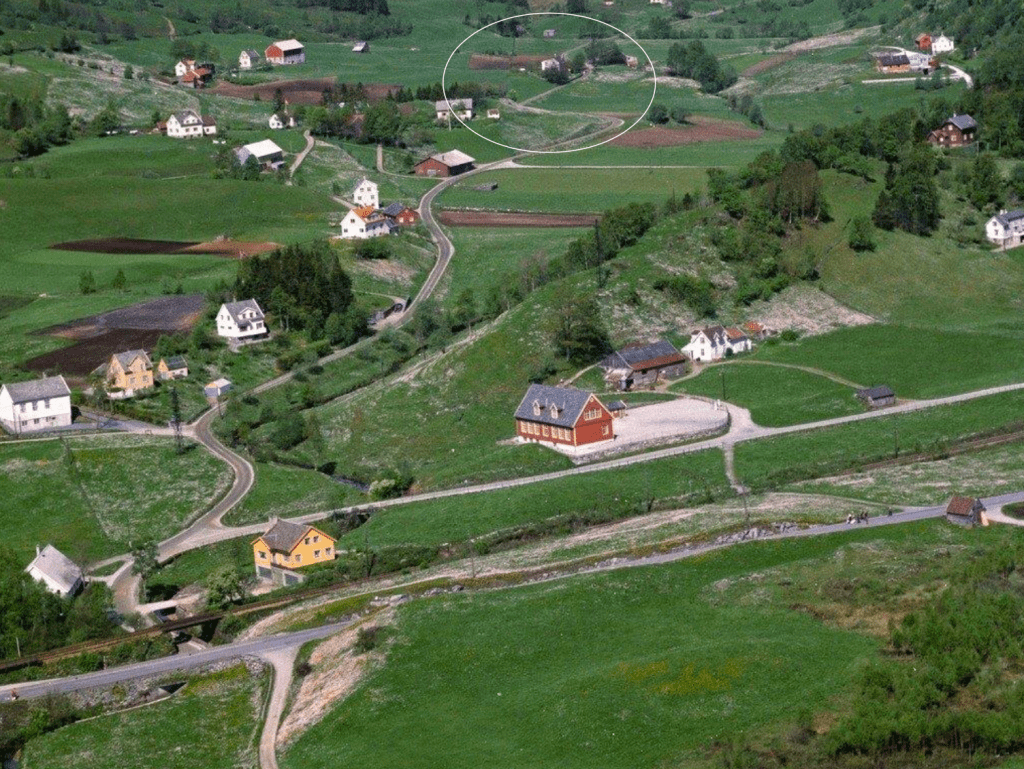

Aerial view of Helgøya and southern Nes (looking northwest); photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrison; downloaded from Wikipedia Bertha was one of seven daughters born in Nes Parish to Agnete Kristiansdatter (1831-1930) and Augustinius Bredesen Thorpe (1834-1912). In order of birth, they were: Dina, Mathea, Bertha, Gina, Andrine, Caroline and Anna. All seven of Agnete and Augustinius’s daughters emigrated as young adults to Wisconsin’s Rock and Dane counties in the 1880 and 90s. Agnete and Augustinius joined their children there in 1891. I believe that Bertha’s sister Mathea was the first in the immediate family to begin this chain migration, arriving in 1882, but other relatives preceded her in 1880 (see below). Around 1882, Erik Veum left Nes for Kristiania (Oslo) and probably departed for the US in 1883. It seems likely that Bertha followed in 1884, and they married in Wisconsin in 1885.

Gina Thorpe Christopherson (1867-1953), Bertha’s sister, is seated second from left (photo downloaded from Ancestry.com) Bertha’s father Augustinius was a husmann (tenant farmer) and kvegrøkter (cattle rancher) who grew up on Helgøya – the island in Lake Mjøsa. We do not know much about either Augustinius or Agnete,[1] but the fact that their seven daughters were born on four different farms suggests to me that they struggled to find consistent employment. Their first daughter, Dina, was born two years before Agnete and Augustinius married in 1860. But Dina was not Augustinius’s first child; in the year before Dina was born, Augustinius fathered two children by two other women.[2]

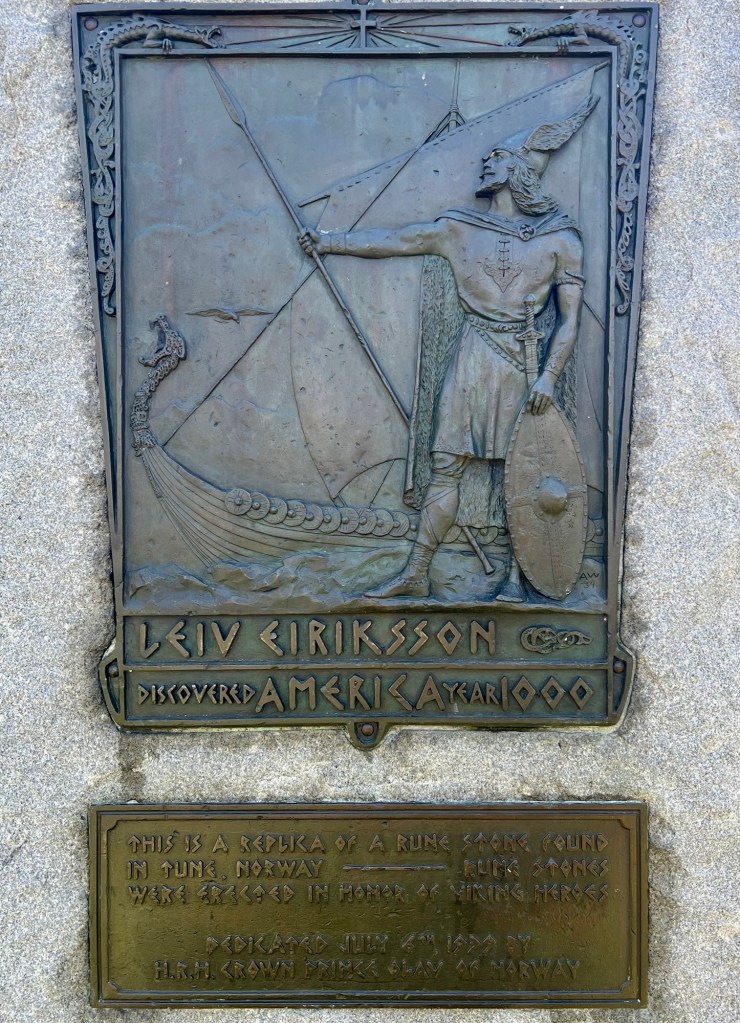

Pedigree chart for Bertha Thorpe Veum

(To see where this fits into my family tree, see Chart J on this page)The historical record tells a similarly complicated tale for Augustinius’s parents, Maria Syversdatter (1799-1866) and Brede Jonsen (1809-1884). Both Maria and Brede were born and raised on Helgøya. Maria was widowed after only three years of marriage to her first husband, Tor Andersen, and qualified to receive flour rations to support herself and her two young sons. She gave birth to a third child two years after Tor died. In 1830, Maria married Brede Jonsen, who had served as a soldier and apprenticed to be a shoemaker.

Maria and Brede went on to have seven children together, including Augustinius (Bertha’s father). Augustinius was born on the Maurud farm, but some of his siblings were born on the Grimsrud and Fjeld farms. After Maria died in 1866, Brede remarried and had two more children with his second wife, Tolline Jonsdatter. In 1883, Brede and Tolline qualified for poverty relief, and a year later Brede hanged himself. Tolline died the following year.

The main building from the Grimsrud Farm (built in 1775 and moved in 1906 to the grounds next to the Hamar Domkirke — the first building of the Hedmarksmuseet)

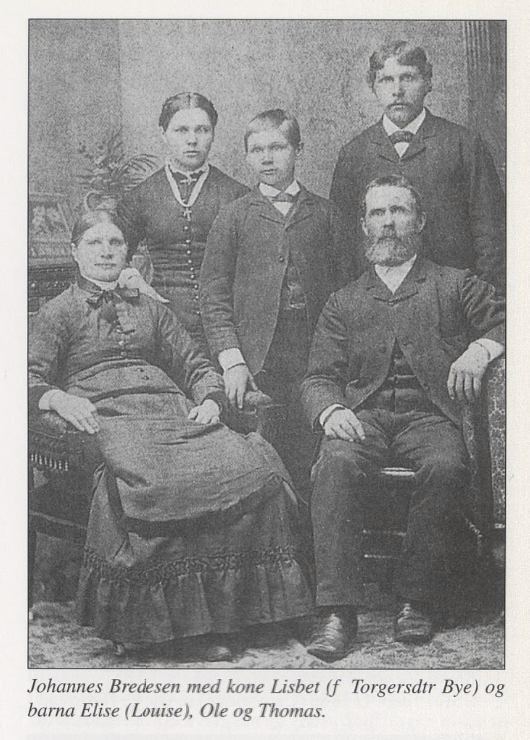

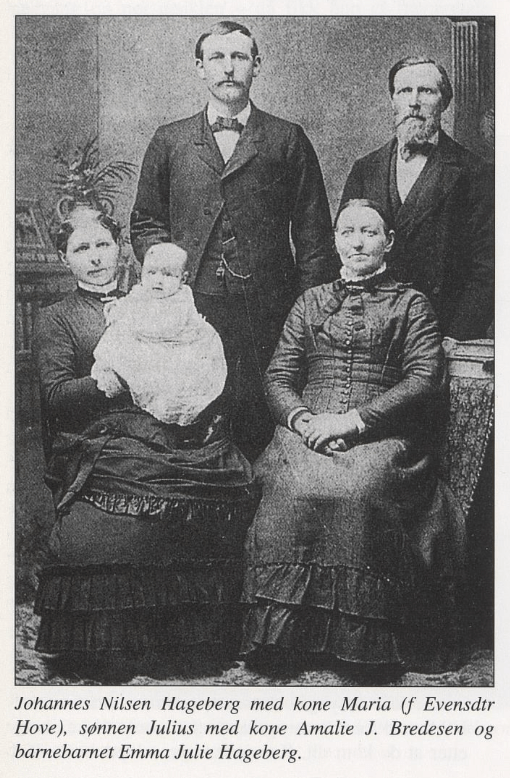

1806 map of Helgøya (Source: https://nesoghelgoyahistorielag.no/2019/04/26/kart-over-helgoya-1806/) If you have followed this so far, I commend you. It’s a confusing story. Details from those last three paragraphs were pulled from Kolstad’s Nes bygdebok, which provides a surprisingly comprehensive account of the family’s history. But the bygdebok actually missed one of Brede’s children. A year before he married Maria in 1830, Brede had a child out of wedlock with a woman named Pernille Iversdatter. This child, Johannes Bredesen, went on to marry Lisbeth Torgersdatter and have seven children of their own. Three of those children settled in or near Edgerton, Wisconsin – i.e., the same area where Erik and Bertha Veum settled. And the first of these to emigrate was Johannes and Lisbeth’s daughter Amalie, who came over in 1880. Johannes and Lisbeth ended up emigrating in 1886 and brought their two youngest children with them.[3] Thus, Bertha had several cousins (as well as sisters) living in the area when she and Erik established themselves in Wisconsin.

Above: Johannes Bredesen family of Edgerton, Wisconsin. Johannes was Augustinius’s half-brother. Reprinted from p. 121 of Nes og Helgøya: Utvandring til USA og Canada i tekst og bilder.

The young woman on the left is Amalie J. Bredesen, daughter of Johannes Bredesen (see prior photo). This family arrived in 1880 and lived in Utica, Wisconsin. Reprinted from p. 122 of Nes og Helgøya: Utvandring til USA og Canada i tekst og bilder. There is so much that is unknown to me about Bertha Thorpe’s family, including why they chose the surname Thorpe upon arrival in the US. I haven’t found evidence that they had lived on a farm of that name in Nes, but there is a bruk called Torp on the Østdal farm. It’s possible some family members worked there before emigrating; although the 1875 Census shows the family living on the bruk called Ramsberg on the Sølsberg farm.

I drove through this area earlier today (May 14, 2025) and took some photos of the countryside. Explorations like this don’t typically yield genealogical insights for me, but they do give me a sense of the place folks came from. Most of the buildings here appear to have been built in the last 100 – 150 years, but it’s not hard to picture what life was like before that. The local economy remains solidly agricultural. If they could see it today, Bertha Thorpe and her ancestors would be amazed by the changes in Norway’s farm technology, but they might be comforted to see that the pace of life in Nes and Helgøya hasn’t changed too drastically.

Dark green = Kolden (Bjørnstad), Dark blue = Ramsberg (Sølsberg), Pink = Nedre Østdal, Light blue = Mølstad, Light green = Svennerud, Orange = Fjeld, Purple = Maurud, Red = Grimsrud

Svennerud

Fjeld

Maurud

Stabbur (store house) at Grimsrud Helgøya Farms

Helgøya Chapel, built in 1870, served as a secret ordination place for 18 priests during the Nazi Occupation in 1944.

Nedre Østdal in Nes

Mølstad

Sølsberg

Sølsberg

Sølsberg

Bjørnstad Nes Farms

[1] Agnete’s family remains a mystery to me. Agnete’s parents were Dorte Gulbrandsdatter (1805-1869) and Kristian Hansen (1806-?), who married at Nes Church on December 4, 1830. Agnete was born on the Mølstad farm the following year. By 1835, the family lived at Nordre Østdal and had a son, Johannes (Agnete’s only known sibling). The 1865 Census shows Dorte living with Agnete and Augustinius on Kolden, a bruk (small land holding) under the Bjørnstad farm. Kristian had probably passed away by then; although Dorte is listed in the census as married, not widowed.

[2] Most of the information in this post comes from Gunhild Kolstad’s Nes bygdebok: Bruks- og slektshistorie, volume 2, section 1 (Helgøya, published 1990) and section 3 (Midtfjerdingen, published 2000).

[3] Details about the Johannes Bredesen family come from pp. 121-122 of Nes og Helgøya: Utvandring til USA og Canada i tekst og bilder, published in 2002 by the Nes historielag.

-

The ancestors of Erik Embretsen Veum, father of J. Oscar Veum

Three years ago, I wrote a blog post about my biological great-grandfather, Johan “Oscar” Veum, even while asserting my belief that family is not biology. I still strongly believe this. You’d think then that I might leave this branch alone. But that’s the funny thing about genealogy; you tug at a thread and it tugs back. You pull out a knot and then feel compelled to untangle it.

My biological great-grandfather’s family has several of these knots. Untangling them has been enlightening. I’ll never have it all figured out, but I’ll walk you through some of my discoveries.

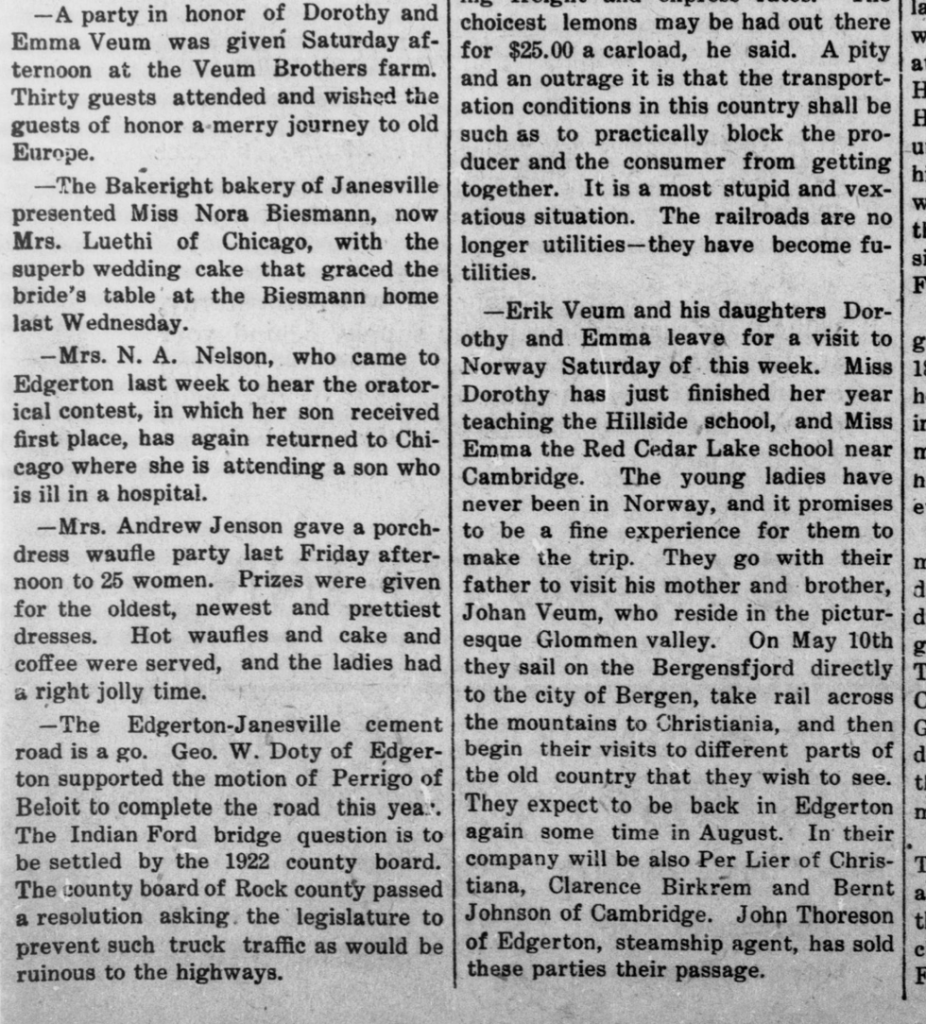

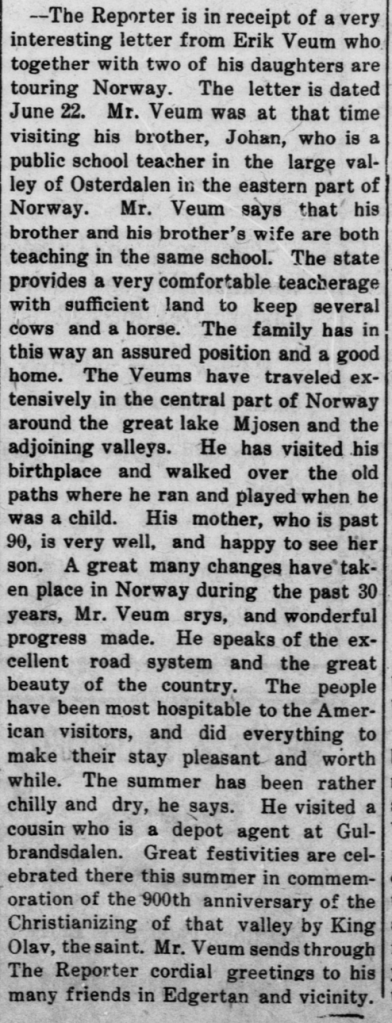

Erik Veum’s passport application In 1921, Oscar Veum’s father Erik Veum traveled from Wisconsin to Norway with his daughters Dorothy and Emma. Erik was 57 then. Their mission was to see family and visit Erik’s old stomping grounds. Two blurbs in the Wisconsin Tobacco Reporter (predecessor of the Edgerton Reporter) describe the journey.

Wisconsin Tobacco Reporter, May 6, 1921

Wisconsin Tobacco Reporter, July 15, 1921 According to the Reporter, Erik, Dorothy and Emma visited Erik’s brother Johan and his family. Johan and his wife Karen were teachers in the Østerdalen area, northeast of Hamar.[1] (Erik’s other brother Petter had been a tailor but had died in 1886, aged 24, only one year after he had married and six weeks after becoming a father.[2])

Erik, Dorothy and Emma also spent time with Erik’s mother Oline, who was 90 years old then. She died two years after their visit. As I wrote in my previous blog post, Oline is an interesting figure because she is listed in the Nes Bygdebok as the operator of two farms, unusual for a woman in that era. Her husband Embret (father to Petter, Erik and Johan) had died at the age of 45. After Embret’s death, Oline purchased the Aarlien farm. Norway’s 1875 Census shows her living on Aarlien with her three sons. Oline managed the farm with the help of a farmhand named Peder Hågensen from 1872 to 1876, and the two married in 1881. She purchased the Veum farm in 1880 and didn’t sell it until 1918, when she was 87.

Pedigree chart for Erik Embretsen Veum

(To see where this fits into my family tree, see Chart J on this page)

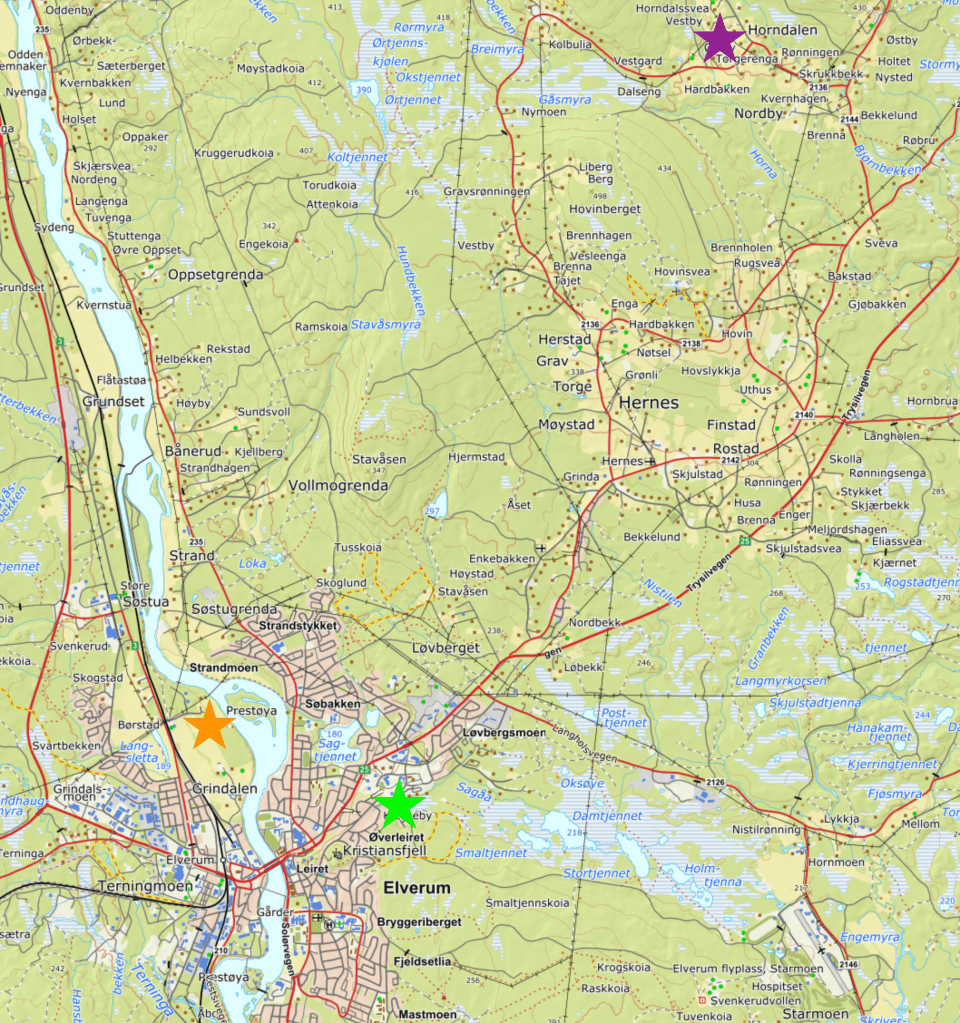

Farm locations: Pink = Veum, Dark blue = Aarlien, Light blue = Berg østre, Green = Løkting / Kjerneby Erik Veum’s father’s family from Løten

Erik’s father Embret (1824-1869) spent his childhood on a farm called Berg østre, located in the parish of Løten, just east of Hamar.[3] On Berg østre the family had been longstanding bygselmenn, meaning they leased the farm but the lease was inheritable. Indeed, the family’s connection to the lease goes back to 1672, when Lars Olsen Kolset (1638-1714) inherited the lease from his first wife’s family. One of Lars’s sons from his second marriage, Embret (1680-1767), inherited the lease and passed it on to his son Erik (1728-1782), who in turn passed it to his son Embret (1764-1808). This Embret’s eldest son, Erik, was only 13 at the time of his father’s death, so the lease transferred to Embret’s wife Ellen.[4]

Ellen remarried in 1809, and the man she wed, Ole Larsen, took over Berg østre. Ellen grew ill and died in 1813; but before she died, she and Ole agreed that the farm would pass to her son Erik when he was old enough to manage it. As Ellen’s affairs were being settled, Ole declared he would hand the farm over to Erik immediately, in exchange for a pension contract (føderåd). Erik struggled financially during those years, as times were tough in Norway following the Napoleonic Wars. When Erik died in 1833 (aged only 37), the family’s debts were so high that his widow Ingeborg Andersdatter had to auction off the lease and other property.

Løten Kirke was the parish church for the family at Berg østre. It was originally built in the late 1100s but has undergone multiple additions and renovations, most recently in 1875.

Photos from my stop at Berg østre It’s not clear where Ingeborg and her four children moved after the auction. But we know that the eldest son, Embret, came into contact with Oline Marie Pedersdatter from the neighboring town of Elverum. They married and spent their first few years together in Hamar (then part of Vang parish). Oline and Embret had their three boys there before the family moved to Nes. My best guess is that they moved to Nes sometime between 1866 and 1869, and they may have lived on the Åsen farm on Helgøya in the years before Embret’s death.

Vang Church, rebuilt 1805-1810 after a fire. Erik Veum’s mother’s family from Elverum

Embret’s wife (Erik’s mother) Oline Marie Pedersdatter was the fourth of six children born to Anne Olsdatter Koppang (1796-1875) and Peder Pedersen Bagstuen Løkting (1799-1854). The documentary evidence suggests that Oline descended from a prestigious family in Elverum. Her father Peder was an accomplished solider, who started his military career as a chief rifleman in the Østerdalen Battalion of the 1st Akershus Infrantry Brigade and was promoted multiple times in his lifetime. He lived at the Kjærnebye (Kjerneby) farm in Øverleiret (today part of Elverum), a property which he had purchased. For a last name, Peder chose his mother’s family name Løkting – a prominent local family that had held the Lille-Grindalen, Østby and Grindalen farms for several generations.[5]

Peder’s great-grandfather Willum Jørgensen Løkting (1680-1726) served under Major General Hans Ernst von Tritschler (portrait of the general shown here). William had been a low-ranking, non-commissioned officer and a tenant on one of the general’s farms. Willum’s father Jørgen had worked as a baker at Kongsvinger Fortress. In 1710, Willum married Dorthe Marie Knudsdatter Hals (1700-1767), daughter of a wealthy captain, Knut Jensen Hals (1660-1725). Within a couple years of their marriage, Willum purchased two properties: Østby in Horndalen and Lille-Grindalen. In 1719, he was permitted to purchase Grindalen from the estate of General von Tritschler.

Willum and Dorthe’s third child, Ole Willumsen Løkting (1722-1768), was a First Lieutenant in the Sønnenfjell Ski Corps. He and his wife Siri Gulbrandsdatter Gobakken (1721-1801) first lived at Lille-Grindalen, and then Ole inherited Østby. Ole died when he was only 56, but Siri ran the farm for another five years.

A tribute to the ski corps in downtown Elverum Ole and Siri’s third child was Oleana Maria Olsdatter Løkting (1756-1832). Oleana became a midwife and married a farmer by the name of Peder Helgesen Bagstuen (1799-1854). Oleana and Peder’s fifth child was the soldier Peder Pedersen, father of Oline Marie Pedersdatter.

Kjerneby / Løkting = green, Lille-Grindalen = orange, Østby = purple

The Løkting estate at Kjerneby is now a suburban housing development

Downtown Elverum Some closing thoughts

I wonder if Erik Veum, visiting his family in Norway in 1921, was aware of the various twists and turns that led his parents from Løten and Elverum to Hamar and then to Nes. If Oline’s mind was still sharp at 90, did she impart any family knowledge to her son and granddaughters? If so, it is lost to time. We are left only with fragments gleaned from the historical record. Fortunately, Erik’s forbears – particularly some in his mother’s line – had the kind of status that leaves a trail. This was not the case with Erik’s wife Bertha’s family, which was of humbler origin. I turn to them in the next post.

The Glomma River in Elverum

Images from my visit to the Glomsdalsmuseet in Elverum. This museum has a collection of nearly 100 historic buildings — some dating back to the early 1600s.

[1] The Nes Bygdebok states that Johan also served as an organist and singer in the Åmot Church, was a member of the Åmot Mens’ Choir, and directed the Rena Workers’ Choir (Arbeidersangforening). See p. 761 in Nes bygdebok. 2 D. 3 : Bruks- og slektshistorie [Midtfjerdingen].

[2] See p. 790 in Nes bygdebok. 2 D. 3 : Bruks- og slektshistorie [Midtfjerdingen]

[3] Spellings varied greatly in these days. Erik is often written as Erich, and Embret can be Ingebret or Engebret. The town of Løten used to be spelled Leuthen. And the Løkting name (see section on Erik’s mother’s family) has many variants: Løchting, Lückting, Løgting, etc.

[4] Information in this paragraph and the next comes from J.B. Morthoff’s (1953) Løtenboka: garder og slekter (bind 2), pp. 711-716.

[5] Information for this section comes from an online article written by Bjørn Rasch, member of the Sør-Østerdal Slektshistorielag (https://www.sor-osterdalslekt.no/lochting.html#_ftn1), and I draw directly from the Elverum Bygdebok as well.

-

The cup that launched a ship

The year is 1850, and in a small village perched at the end of a fjord in Western Norway, a young servant hurries through her tasks. Malene has no education and very little savings, but for the first time in her life she is hopeful. Earlier that year a young man named Ole had come to the village from Bergen, looking for work. He didn’t find much work, but he found her.

Malene’s mind races ahead to when she can leave her employer’s house and meet him. The clock ticks. Her heartbeat overtakes it. One more hour. She turns abruptly, and in the corner of her eye she notices that she has dislodged a porcelein cup from its shelf.

It falls and she spins back to catch it, but…

The opulent furnishings of the dining room do nothing to muffle the sound of shattered china. Malene panics. Has anyone heard? There are no footsteps. No one calls out. Gingerly, she removes all the shards from the floorboards, some pieces as thin as grass blades, and places them in a rag.

She moves now, as if in a dream, out of the fine home and into the muddy road. She’s clutching the jumble of porcelain in the folds of her dress. Within a few minutes she’s home and Ole is there, too. Wordlessly, she shows him what she carries.

They stay up for hours, debating how to handle the situation. The plan was to marry at the village church later that summer and set sail for America after the harvest. But neither of them can afford to replace the cup. Attempting to do so would spoil those plans completely. Ole mentions that a ship to New York City would be leaving from Bergen on Wednesday of the following week. What if they were on it? [1]

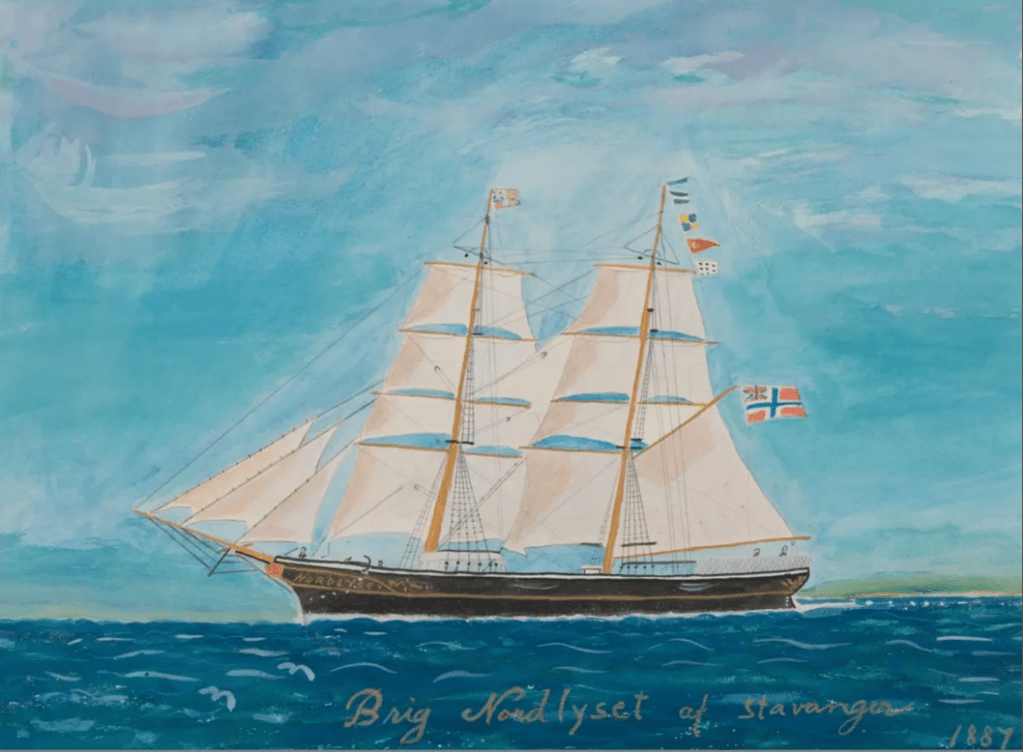

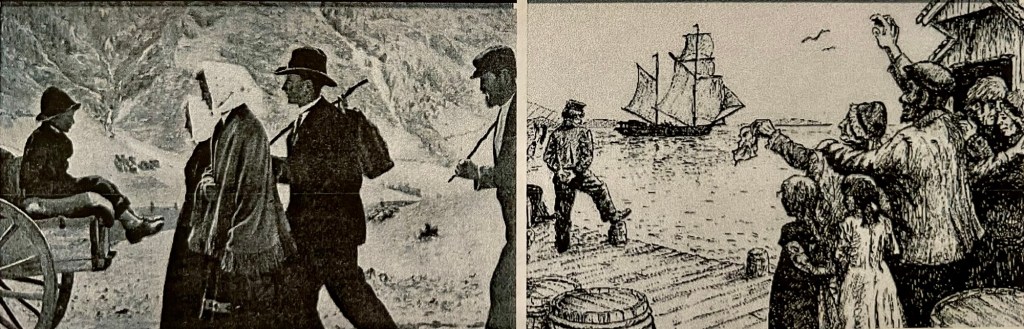

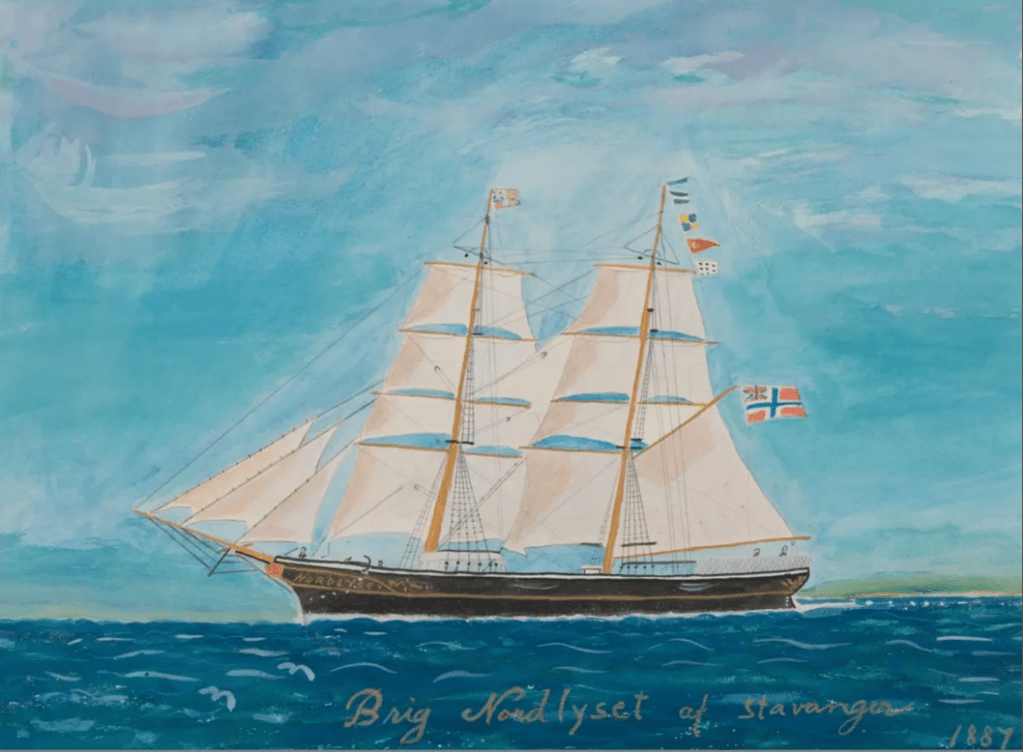

Artwork by Robert Strati: https://sites.google.com/echobig.com/robert-strati/home We don’t know if the story about the broken cup is true — and we certainly don’t know if my imaginings above are accurate — but according to the church records for Førde, Malene Olsdatter Bruland was the parish’s first emigrant to America. She left on May 2nd, 1850. Six days later, she and Ole Jensen Hauge boarded the Nordlyset in Bergen and arrived into New York harbor on July 11th.

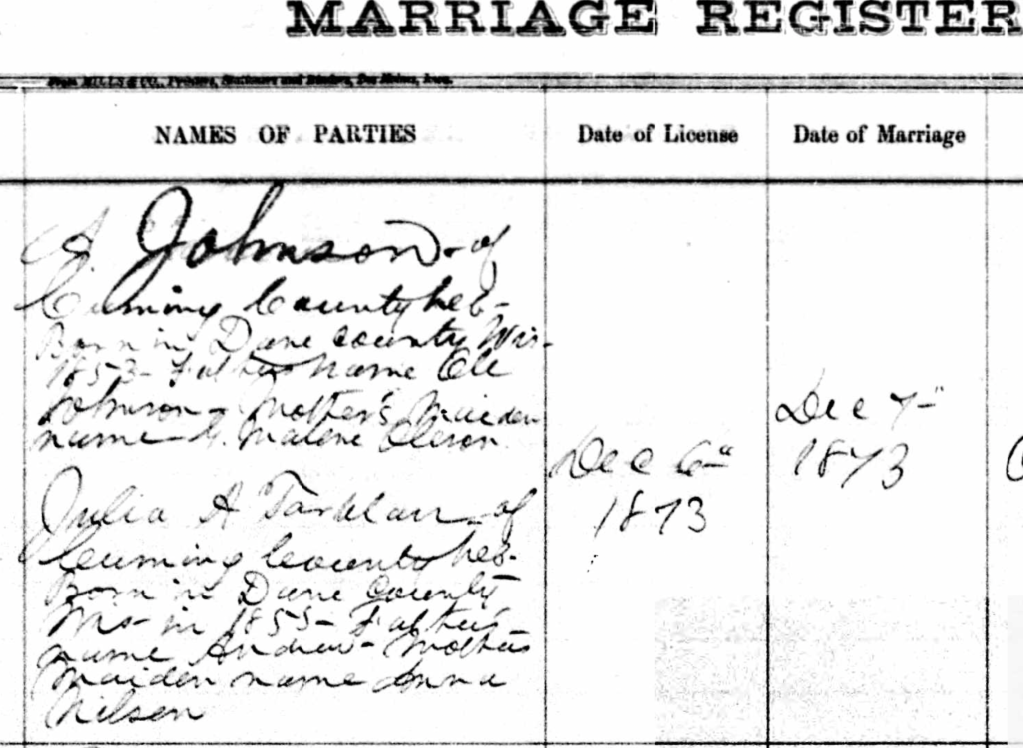

Malene and Ole were my great-great-great grandparents (paternal grandparents of my great-grandma Jessie Johnson Reiner).

The Brig Nordlyset (Stavanger Maritime Museum)

Excerpt from Historia om Førde – Bind 2 (published 2023) Local historian Stig Årdal discovered Malene’s out-migration entry in the church records and traced Malene and Ole’s journey to Wisconsin. In an article (see photo above), Årdal noted that Ole married a woman by the name of Susanna Strand in 1867, and he hypothesized that Malene had died prior to this.

Mr. Årdal was correct. We know that Malene, who went by Malinda in the U.S., passed away in 1865 at only 41 years of age, leaving behind a grieving husband and four children. Her grave lies next to that of Ole and Ole’s second wife at Hauge Cemetery near Deerfield, Wisconsin.

Hauge Cemetery near Deerfield, Wisconsin, where Ole and Malene (Malinda) and Susanna are buried Because she died at a young age and Ole remarried, little information about Malene was passed down in the family. We’re left only with the story about the broken cup — and with bits and pieces from the historical record. But even these scraps were hard won.[2]

* * *

I’ve traveled to Førde to see the place that Malene left behind so quickly, and to try to understand what her life was like in this place many years ago.

Prior to coming here, I reached out to an online group of local history enthusiasts, and I was extremely grateful to receive some excellent help. A local author, Mr. Vidar Fossen, helped me confirm some of the research I had done using the church books and the Førde bygdebok. But Mr. Fossen went further and pointed out some interesting quandaries in the historical record.

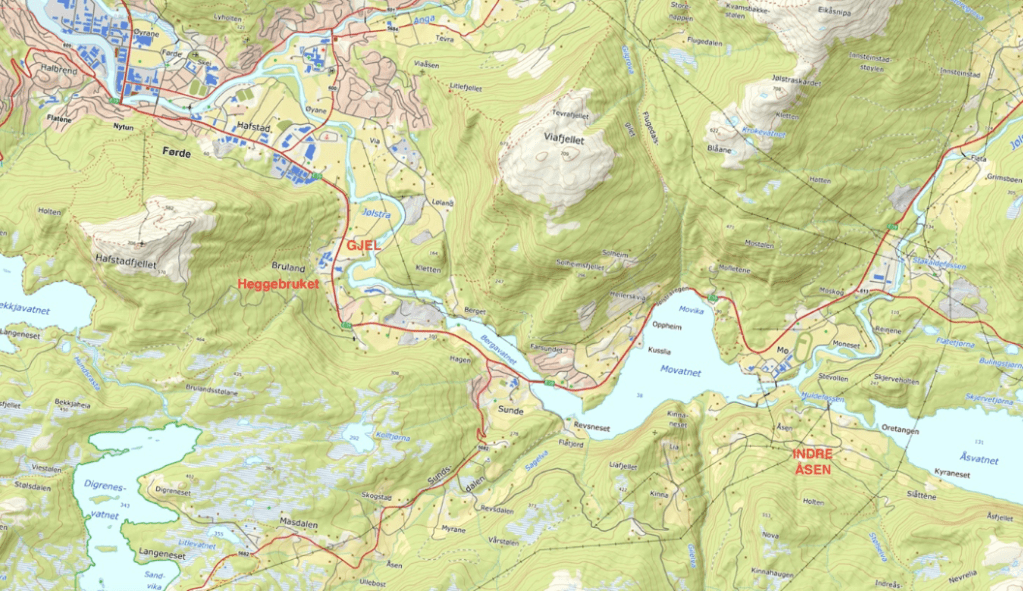

For instance, the bygdebok states that Malene was the only child born to Ole Gundersen Bruland (1771-1847) and Kirsti Andersdatter Åsane (1792-1851). But there is very little information about Malene’s father Ole Gundersen. In the 1824 marriage record for Kirsti and Ole, the church book states that Ole’s father’s name is Gunder Olsen. But Fossen believes that the priest may have written this in error. The bygdebok indicates that Malene’s family lived on a farmstead (bruk) within Bruland called Heggefjellet. In this same area there’s a farmstead Heggebruket run by Jakob Gundersen, who was a son of Gunder Rasmussen from Gjel. Fossen thinks Malene’s father Ole may have been another son of this man. Unfortunately, there is a gap in the church records from this era, and Ole’s 1771 birth falls into this gap, so we can’t know for sure. But another clue that ties Ole to the Gunder Rasmussen family is that one of Malene’s godmothers at her 1824 baptism was the daughter of Jakob Gundersen.

Mr. Fossen notes that Kirsti remarried in 1837 to a man named Matias Nilsen Åsane, but her first husband Ole Gundersen (Malene’s father) was still alive then — he died in 1847. Thus, it may be the case that Kirsti left Ole for Matias, unusual but not impossible for that time.

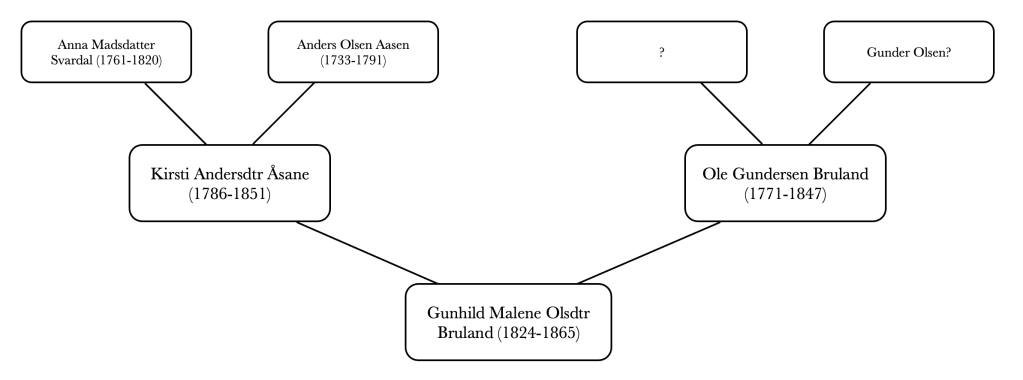

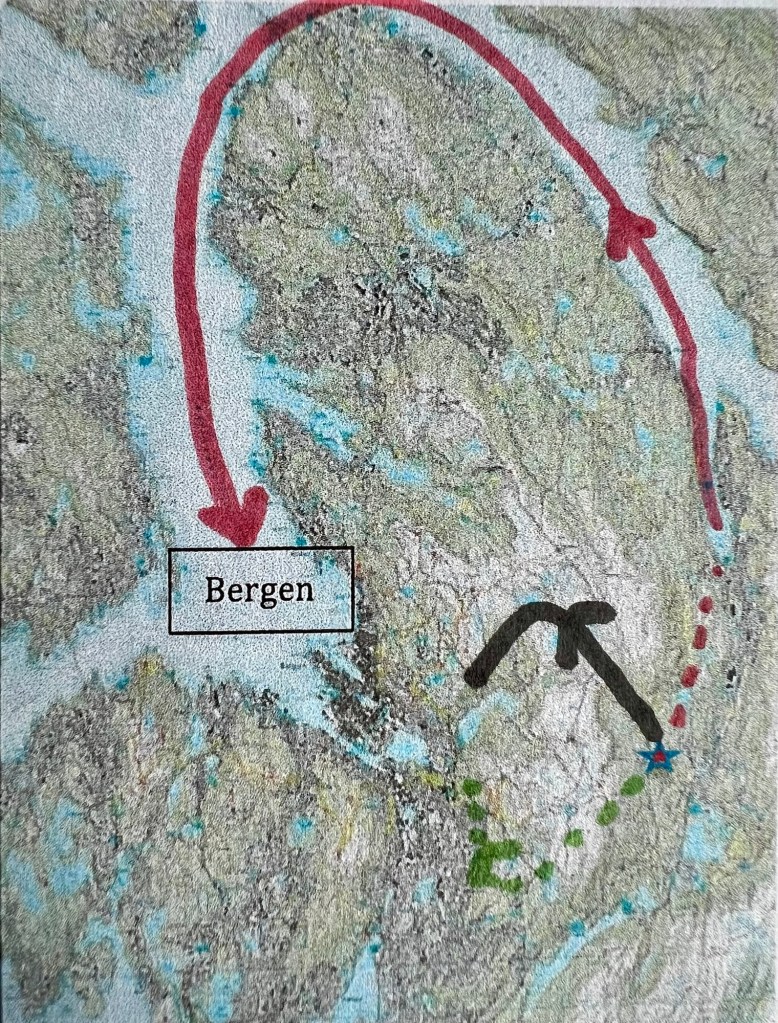

Map of the relevant farm locations, courtesy of Vidar Fossen Fortunately, Kirsti’s origins are easier to trace than her husband’s. Kirsti was born to Anna Madsdatter Svardal (1761-1820) and Anders Olsen Aasen (1733-1791). As that large age gap between her parents suggests, Kirsti was born from her father Anders’s second marriage. She had six older half siblings, in addition to two full brothers.

Kirsti grew up on the Åsane farm — Bruk 5, Indre Åsane, to be precise. Fossen tells me that Indre Åsane was not farmed by my family members after 1847, but the descendants of Kirsti’s siblings and half-siblings are likely to live in the area.

Pedigree of Malene Olsdatter Bruland

(To understand where this fits in my family tree, see Chart B on this page)I was unable to meet Mr. Fossen in person and thank him for all of the excellent research he kindly conducted on my behalf, but he put me in touch with three warm-hearted locals, who generously gave up their time today to give me a guided tour of the area. This was no ordinary tour — it was a tour they especially created for me to walk in my great-great-great grandmother’s footsteps. I am overwhelmed by their generosity.

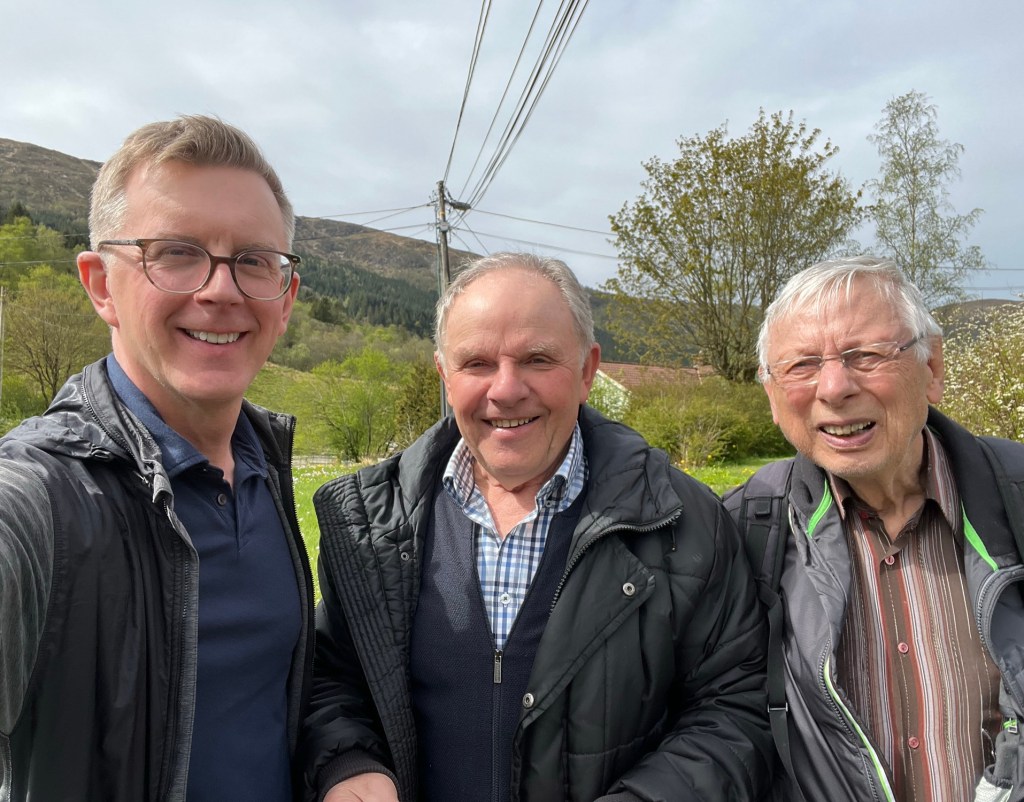

I would like to introduce you to these dear people. They are (from left to right in the photo below): Ove Farsund, Judith Hegrenes, and Erik Olav Hagen. Each one of them has a wealth of local knowledge, but combined, the three of them have an encyclopedic understanding of their community. I felt like they brought me up to speed on what my family has missed here these past 175 years.

We are standing in front of the Førde Church, which was rebuilt in 1885 (after the time my ancestor immigrated) to make space for a larger congregation.

Our first stop was the Førde Church. The church’s magnificent altarpiece dates from 1643. Speaking of 175 years, it was 175 years ago today (May 8th) that my ancestor Malene Olsdatter Bruland sailed from Bergen for America. I had not planned my trip with this date in mind, so when I discovered this fact, I felt like Malene was winking at me from the beyond.

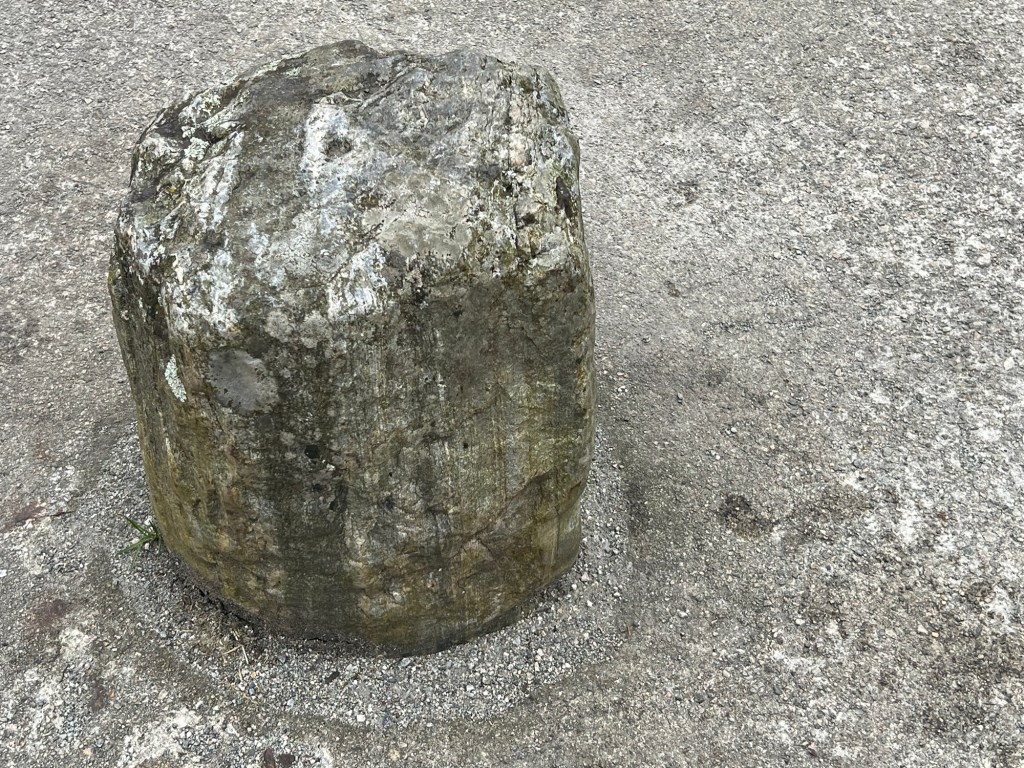

It was actually from the spot below that Malene left Førde. This was the port and the most important transportation hub in Førde in the days before trains, cars and buses.

Førde fjord

An old mooring post

The dock at Steinavegen As I mention above, Malene grew up on one of the many bruk that comprised the Bruland farms. My guides took me to the exact spot where Malene once lived:

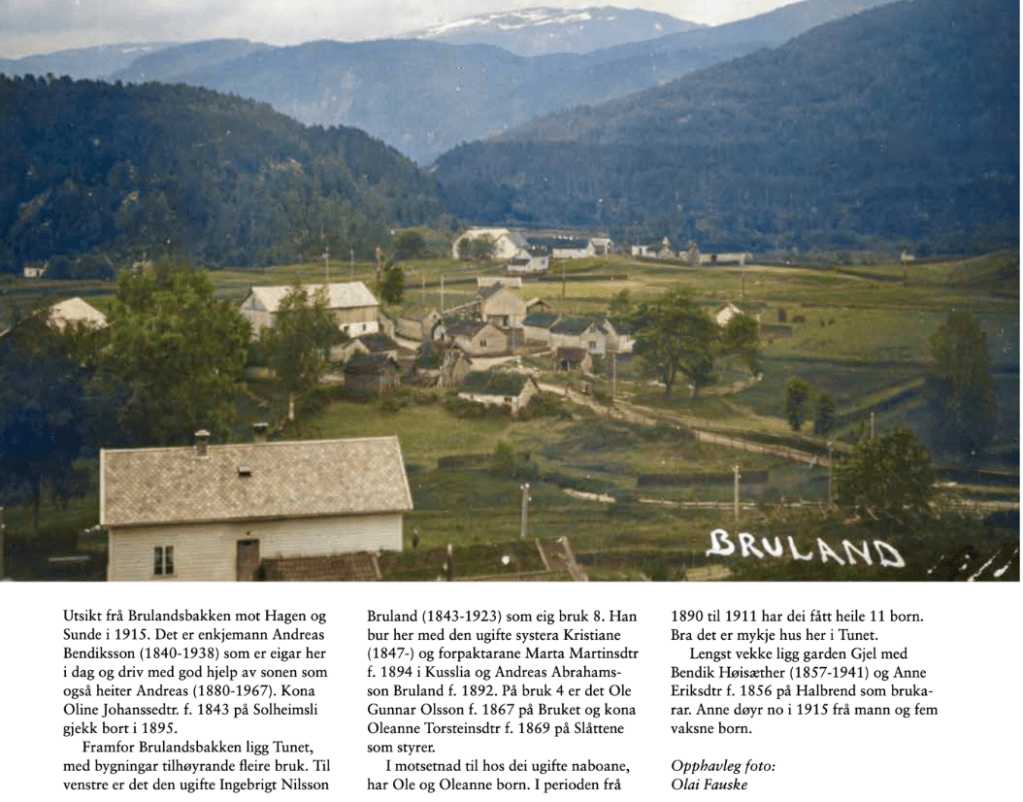

Heggefjellet on Bruland or what today is referred to as Per Tunet

A 1915 photo of Bruland (Tunet and Gjel farm buildings), reproduced courtesy of Vidar Fossen from one of the books he wrote, “Gamle Førde i Fargar” Most of the buildings on this site today were built after Malene left, but they are built in a traditional style that pays respect to the area’s history. The property is now owned by Siv Bruland and Alv Avedal.

This building, now used as a garage, probably looked very similar in Malene’s time. Interestingly, the house that once stood at Heggefjellet was moved to a property across the road, owned by Siv’s mother Signe Bruland. Years ago, the family used the house as a rental property for fishermen who came seeking the giant salmon and trout that thrived in the Jølstra River. Today, Signe has transformed this place into a magical spot — a delightfully furnished guest home surrounded by immaculate gardens. Stepping into this home, I knew I was literally walking in my 3x great-grandmother’s footsteps — she may have personally lived here. And even if not, she would have known this house well.

From left: Judith Hegrenes, Signe Bruland, Jesse Rude, Siv Bruland, and Erik Olav Hagen (photo taken by Ove Farsund)

Traditional implements used to make rømaske (a pudding made from the first milk of a cow that has just given birth)

Signe and her daughter Siv Bruland From here our group traveled to Åsane, to see the farm where Malene’s mother Kirsti Andersdatter grew up. Today the farm is owned and operated by Ole Johan Åsane, who took time out of his busy schedule — it’s currently lambing season — to show us around the property. Åsane is tucked away in the uplands beyond the Huldafossen Waterfall. The farms up here have breathtaking views of the mountains.

The view from Åsane

Some photos to give you the flavor of the countryside here — near the Kinnaneset, Kinna and Lia farms

Our group in front of the Huldafossen. The waterfall is named after a kind of mythical being, the huldra. According Scandinavian folklore, huldre inhabited the forests and could help or harm humans. One of our final stops of the day was at the bruk called Gjel at Bruland. As I write above, Mr. Fossen believes (and I’m inclined to agree!) that Malene’s father Ole Gundersen Bruland came from this farm. Gjel lies on a serene bend in the Jølstra River. Here the current owner, Mr. Høgseth, has been working hard to revive and conserve the native salmon population.

The farm as it used to look

Outbuildings at Gjel

The stabbur (store house), raised to protect from mice

Along the Jølstra

Mr. Høgseth and I I could probably make this post 10 times longer without trying too hard — my generous hosts packed so much into this amazing day for me.

I will simply conclude by saying that my ancestor Malene Olsdatter left this area 175 years ago with a mixture of emotions that I can only imagine — sadness over saying goodbye to loved ones, excitement for a new life with her fiancé, and probably a healthy dose of fear about what was in store for her in America. Tomorrow morning I’ll be leaving Førde with a different set of mixed emotions: joy over making new friends, gratitude for all of the kindness that was shown to me here, and a pang of regret for the shortness of my visit. I hope I can make it back here one day.

A fjordhest and her foal

The view from Solheim over Movatnet and the Jølstra River Valley

[1] I took a great deal of artistic liberty with the italicized introduction to this post. This “dramatization” is based on fragments of a story passed down in our family. We have no evidence that Ole was actually in Førde, but the family story that was passed down (see this post) suggests he was there. Church records show that Ole migrated out of the parish on April 16th, 1849 — “to Bergen”. We might assume he left Bergen for Førde sometime later that year or in early 1850.

[2] Not everyone wants to read how the genealogical sausage gets made, so I’ll footnote this: Locating the correct Malene Olsdatter Bruland was a long process. In 1975, my great-aunt Helen wrote to the renowned Norwegian-American genealogist Gerhard Naeseth asking for help. Mr. Naeseth managed to find Ole and Malene’s names on the ship manifest of the brig Nordlyset, but when it came to their families of origin, even he was at a loss. He suggested Helen solicit the help of a scholar in Bergen by the name of Lars Oyane, and Helen wrote him immediately.

Mr. Oyane did some research and could not discover any trace of Ole Jensen Hauge. This was because he was looking for Ole in the area near Førde — a logical but false assumption. (We now know that Ole was from Arna, near Bergen. I wrote about his origins in this post.) And regarding Malene, Mr. Oyane concluded that she was born Louise Malene Olsdatter on the Bruland farm in Førde in 1824. But what Oyane had overlooked was that there was another Malene Olsdatter born on the Bruland farm in 1824. Last year I discovered this Malene in the Førde bygdebok with the note: “Gunhild Malene. f. 1824, det var truleg ho som kalla seg Malene Olsdatter og emigrerte til Amerika den 2. mai 1850, den første registrerte Amerika-farar frå Førde” (Gunhild Malene b. 1824, it is believed she called herself Malene Olsdatter and emigrated to America on the 2nd of May, 1850, the first registered emigrant to America from Førde).

Could that be right? Bygdebøker are secondary sources and not as reliable as the primary sources they are based on. For several months I tried to find some kind of evidence — documentary or DNA — that would establish which Malene was ours. Eventually I gave up and asked for help from the local archivists at Vestland fylkeskommune. To my surprise and delight, Ms. Anett Ytre-Eide at the archives got back to me with conclusive evidence that Louise Malene had stayed in Norway until the end of her life, while Gunhild Malene disappeared from Norway’s records in 1850. Neither first name (Louise nor Gunhild) are used in any American documents I can find, but if you look carefully at the Nebraska marriage record for my great-great grandparents, Albert and Julia Johnson, it does appear to list Albert’s mother’s maiden name as “G. Malene Oleson”. (Incidentally, Albert and Julia moved back to Wisconsin shortly after marrying in Nebraska.)

-

A history of the Hauge farms of the Arna Valley, by Ole Johan Hauge

When I was preparing for this trip to Norway, I posted on a Facebook page for the community of Arna that I was seeking some local history expertise. I had discovered that my great-great-great grandfather, Ole Jensen Hauge, emigrated from Arna, but I didn’t know anything about the area. Local volunteers kindly came to my aid and put me in touch with two people: Arne Storlid, a distant relation of mine, and Ole Johan Hauge, a local history expert. I had the great pleasure of meeting Ole Johan Hauge this morning, and then we went together to meet Arne Storlid. (I write about that meeting here.)

Ole Johan Hauge and I — out on the Hauge Farm, Arna, Norway These days Ole Johan is a volunteer teacher at the Espeland Prison Camp Museum, the only preserved prison from Norway’s occupation era. Formerly, Ole Johan was the chairman of the museum’s foundation. The facility at Espeland was set up by the Nazis to incarcerate political prisoners, and it stands as a testament to the horrors inflicted during the occupation. Before he retired, Ole Johan worked around the world for over 25 years for the International Red Cross. His last call of duty was in North Korea, but he also helped direct the rescue operation after the tsunami disaster in Indonesia in 2005. Additionally, he worked in Sri Lanka, Bosnia during the war, in China, Myanmar, Lebanon and Malaysia.

Ole Johan Hauge’s family hails from one of the several Hauge farms clustered in Arna’s Langedalen Valley — not the one where my immigrant ancestor grew up but one close by. Still, it’s likely that he and I are distantly related.

A few weeks before my visit, I had asked Ole Johan if he would be willing to meet me for a coffee and tell me a little about the local history, particularly about the conditions in those years when locals like my ancestor Ole Jensen sailed for America. Ole Johan agreed, and then he went the extra mile: he actually wrote a local history of the Hauge farms and sent it to me. This act of generosity completely floored me. I have done my best to translate Ole Johan’s excellent history, and I’ve pasted it below, along with the photos and drawings he included. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

A HISTORY OF THE HAUGE FARMS OF THE ARNA VALLEY, written by Ole Johan Hauge

The Hauge farms in the 1800s

The green valley of our childhood, Langedalen, is located within the lovely Arna Valley and about 20 kilometers from the center of Bergen. Beautifully situated in this valley in one of the side valleys popularly called Oladalen are several Hauge farms (“Haugegårder”).

The green valley of our childhood (Hauge Farm is circled) In the 19th century, Norway was a poor farming country with little contact with the rest of Europe. That was also the case in Arna. There were many small farms that could not feed many people. And there were many children in the families then, and only the eldest son (odelsgutt) could take over the farm. The rest of the children had to find work outside the village as there was little industry in the 1800s.

It was hard to do farm work in Vestland, steep slopes and and much heavy labor. Everyone on the farm had to pitch in, and from the time they were little the kids had to work too.

But when the children grew up, most of the children in a family had to make a choice. The oldest boy took over the farm, the girls were married off, and the rest of the sons had to find something to do outside the village. So they had to leave, and the closest place where many settled was Bergen. Or they went to other industrial towns in Vestland. And for some the dream was to come to America.

Dreaming of America

Early on, the youngest boys in the large families were dreaming of getting out and finding a place to live and work. For many, the dream of America, far away on the other side of the ocean, was just that — a dream. But some took the chance and set out.

It was tough to say farewell to home and everyone who lived there, but for many this was the only way out.

The voyage across the ocean was a long and tiring journey, and many were probably afraid of what awaited them in an unknown country.

Once in America it was a matter of finding a place they could settle down and work the land.

For many this was a tough existence, but most managed to build a life for themselves in that new land. They could never, however, forget those they left behind in Norway.

The community school (omgangsskolen)

At the beginning of the 19th century, there was no regular schooling for children who grew up in the countryside. Sometimes a “community teacher” (omgangslærer) would come to the village. He would live on one of the larger farms and the children would come to that farm. School was held in the main room on the farm, and the community teacher would be there for several weeks. Such community schools continued until the 1880s. Of course, they did not exist in the cities.

Here is a drawing depicting teaching in a so-called community school in the countryside of Norway at the beginning of the 19th century.

The photo shows children who were provided community schooling in the 19th century.

Borgaskaret, an important pathway

When the farmers of Hauge went to Bergen to sell or exchange their farm products, the trip over the mountain to Bergen was the shortest way. Then they had to go via the Borgaskaret Path over the mountain to the city.

Borgaskaret has been an important route to get from Langedalen and over Byfjellet to Bergen. This path was for hundreds of years the most common way to get to Bjørgvin town (the old name for Bergen) where the farmers of Langedalen could exchange important trade goods.

There was another path you could take if you wanted to go from Langedalen to Bergen, and that was the old postal road. It went over Natland and Kolstien, through Erdalen, over Bratland and then down through the slopes to Hauge. From there it went on over to Lone, Espeland and on to Arna and Garnes. But this road came much later when people started using carts and horses to transport goods. The trip via Borgeskaret was only for those who walked on foot and carried their goods on their backs.

Until the postal road was put into use, the path up Borgaskaret was the most commonly used. If there was something that needed to be traded, whether it was meat, potatoes or milk, you had to walk Borgaskaret with a load on your back, and it was an effort like no other. Those who have walked that path know that it is terribly steep up from Borge even without a huge load on your back. People from Fjellgården and Unneland also had to take this road when they were going to town. There is a place between Londalen and Hauge that is still called Odlandsskaret because the folks from Unneland used to come here walking over Neset and Lone via Odlandsskarert to Hauge and so on to Borgaskaret. Through the mountain pass, the path continued to the other side of the mountain and down to Tarlebø, past Svartediket and down to Kalfaret.

The star marks the Hauge farms, the black road is the Borgaskaret, the green is the postal road, and the red is the sea route. Borgaskaret was the shortest but the hardest for carrying heavy goods, the postal road was longer but easier. And the sea route was long but allowed you to bring many goods to barter with. Settlement on Hauge in the Viking Age

The farm Hauge is located up in Langedalen, beautifully situated in the shelter of “Hauafjellet”. People have lived on Hauge since the early Middle Ages, but the land was used as far back as the early Viking Age.

There is a written record of farms and ownership from 1519, and at that time it was Sigmund on Hauge who was the owner. He was born in the 1450s and is the first of our ancestors whose name we know. Already in the Viking Age there were people who farmed in Langedalen. It was usually noble families in Bjørgvin who owned the land around the town, and they usually hired slaves or others to farm for them. In the beginning, no one lived where the land was; that happened when the land began to yield a return. Only later did people settle in the valley, but they did not own the land. The valley was at that time divided in two: the southern part went from Borge southwards all the way to Unneland, and the northern part went from Borge northwards. This is how Langedalen was divided for hundreds of years.

The entire Langedalen was under “Skjold Skipreide”. A skipreide was an administrative division of Norway into geographically delimited areas where the inhabitants were collectively responsible for building, maintaining, equipping and manning a leidang ship. The skipreides were not only located on the coast.

Exactly how old the skipreide division is is not known, but the skipreides originated together with the leidang system, and according to Snorri Sturlason, the laws were developed/improved under Håkon the Good and Sigurd Jarl in the mid-900s.

Towards the end of the 13th century, the skipreides became used only for fiscal purposes, and they remained the basis for tax administration until the 1660s. Skjold Skipreide was one of eleven skipreides in Nordhordland, which included large parts of the current Bergen municipality.

The first settlement on what is today Hauge was sometime in the late Viking Age. Two families, probably from Fana in Skjold Skipreide, are said to have come and settled in the valley where the Hauge farm is located. They settled there and built a house together – two families with a common living room but each one with its own space on the short sides of the house. Then they began to cultivate the land just below what we today call Byfjellet Mountain. It was quite common during that time to use slaves for the heavy farm work.

The first farmer on Hauge that we know anything about is Sigmund on Hauge who was born around 1450. Most of the church books before that time have been burned, and it is impossible to find previous owners. So it is likely that there have been landowning farmers on Hauge long before 1450.

The conflict between the Baglers and the Birkebeiners

We know that there were farms on Hauge and Borge when the conflict between the Birkebeiners and the Baglers* was at its worst in the 13th century. Many legends from this time still survive. One of these is related to the Hauge farm. The Baglers who lived in Bjørgvin had learned that the Birkebeiners were heading west to subdue the town. Afraid of being caught with their trousers down, the Baglers sent some soldiers up to Byfjellet to see if they could discover the Birkebeiners before they came over the mountain. One night with a full moon, they saw to their horror that hundreds of soldiers were lined up down on the Borge and Hauge farms. They ran down to the town where all the church bells were rung to warn the townspeople of the danger that was lurking.

But nothing happened, and the next evening the soldiers went up again and then down to Langedalen. Great was the surprise when they discovered that the “soldiers” were corn stalks – not Birkebeiners. But later the real soldiers did come and they defeated the Baglers down in Bjørgvin. This story has been told for generation after generation.

The “skaffers” on Hauge

The old postal route between Bergen and Christiania (Oslo) went via the Hauge farm, and in the 18th century the farm became part of the so-called skyss-stasjon system of the Norwegian government. This meant that the farm had to provide rested and healthy horses when someone came on public business. There were many such “skyss stations” or “skaffer farms” on the long route between Bergen and the capital, and this system worked excellently. Eventually, the farmers on Hauge were nicknamed “Skaffer” Lars, “Skaffer” Ola and so on. It was an honor to become a skaffer farm, which also meant that everything had to be in order. The horses were well-groomed and in order, and pretty much as the public demanded.

Throughout history, many officials came by postal road over the mountain and down to Hauge. There they changed horses before continuing their journey east. This was a service that meant a lot to the farms that were part of the skyss-station service, and the arrangement lasted for several hundred years.

A new era

When the train came to Indre Arna in 1885, it was the start of a new era Up until 1880, there was almost no development in Arna. There were mostly small farms and large families with children. Therefore, most of the youngest boys in the families left the village to find work. It was either to Bergen or to other places in Western Norway. Many also went over the sea to America. Young people from most families in Vestland went to America in the 19th century.

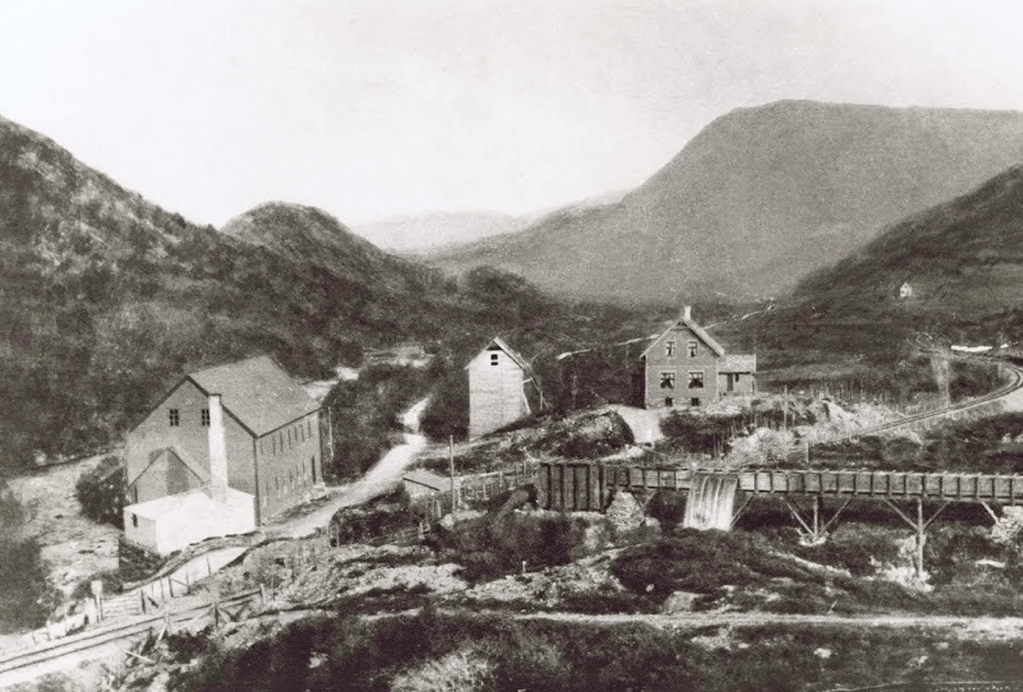

In 1885, something important happened for the development in the Arna Valley. The railway between Oslo and Voss was extended all the way to Bergen, and it was a great revolution for the development of Arna and Hauge. Thanks to the railway, several industrial leaders began to see the possibility of establishing industry in the village. There was plenty of electric power from the surrounding mountains, and in 1895 the Janus factory in Espeland was established.** This meant that the young people did not have to leave the village but could find a job near the farm.

Here the Janus factory set up its first building, and the venture was underway.

When the Janus factory was established, major changes occurred in the Arna Valley Around the Janus factory, many homes were built for those who worked at the factory. In addition, there were shops and schoolhouses. This meant that those children in the family who could not live on the farms could find work at Janus, which many did. With the arrival of the railway, the road into Bergen was not so long, and many could have jobs in the city while living in Arna. After 1900, so much happened in the Arna Valley and it developed rapidly.

* A note from your translator: The Birkebeiners (Birkebeinerne) and Baglers were two rival factions in the Norwegian civil war era (1130-1240). They supported different contenders for the throne of Norway and controlled different regions of the country until the reign of Haakon IV, the king who is generally credited with reunifying the country.

** Janus produces woolen knitwear and is one of the oldest knitwear factories in Europe.

-

Oh, those Johnsons

My grandmother’s Aunt Glenrose – my great-great aunt – was a beloved character, full of stories, jokes and poems. A spinster for life, she was always taking care of others in the family: nursing parents and siblings through sickness and old age, looking after one and then the next generation of children. My parents sometimes left me in Aunt Glenrose’s care when they were busy with work or school, and I can still picture my dear, white-haired auntie sitting in her chair, launching into a recitation of a poem she knew by heart.

Aunt Glenrose as I remember her in the mid-to-late 1970s Some of her favorite stories were about her own family. Glenrose Johnson was the last of 11 siblings, and before her mind clouded over with dementia, she could regale you for hours with funny episodes from her youth. She would giggle recalling when she introduced herself at school as yet another Johnson sibling. “Oh, those Johnsons,” a local gossip had remarked, “They are so prolific!”

Glenrose with her brothers George and Leslie (circa 1903) And it’s true. We are! When I was a child, I knew about Glenrose’s siblings and the large generations of Johnson descendants that followed. What I didn’t know was that Glenrose’s father Albert had four siblings and one half-sibling, and Albert’s father Ole – our immigrant ancestor – had at least seven siblings.

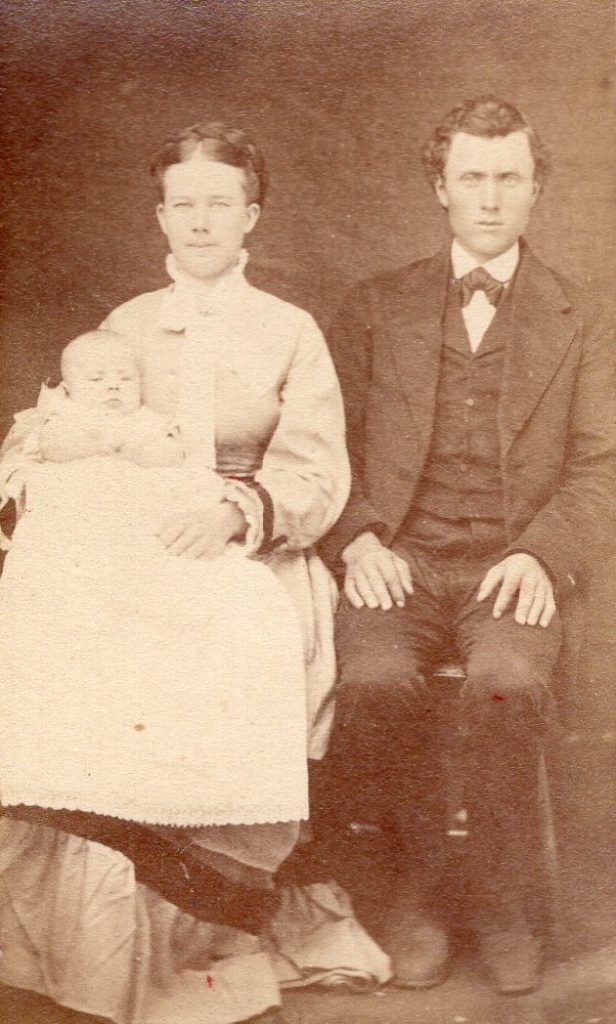

Albert and Julia Johnson with one of their first children, 1870s (Albert was the son of Ole Jensen Hauge and Malene Olsdatter) Ole’s origins had been a mystery for quite a long time. According to the family history that Glenrose wrote in the 1970s, Ole Jensen Hauge was born in Bergen, Norway in 1826, immigrated to Wisconsin in 1850 with Malene Olsdatter (his bride-to-be), and operated a farm in the area of Deerfield, Wisconsin. He changed the family’s name to Johnson at some point, probably to seem more American. Glenrose had listed Ole’s parents’ names in her book – Jens and Marie – but we knew nothing about them.

Right before my trip to Norway in 2022, I discovered the records I’d been looking for; I found Ole’s baptism record in the church book for Haus Parish (located just outside Bergen) and his parents’ names matched up. I rushed to locate the Hauge farm in Haus and made sure to drive by it when I arrived in Bergen (see this post). But a few months ago I discovered a problem: Haus had more than one Hauge farm, and I had gone to the wrong one.[1]

Today I corrected that error.

Hauge farm in Arna’s Langedalen marked above Today I had the pleasure of speaking with a local historian named Ole Johan Hauge, who met me for coffee and gave me tour of the Arna Valley — a beautiful valley that lies just east of Bergen and stretches from Arna in the north to Fana in south. Towards the middle of that valley is a kind of side valley called Langedalen. This is the area where my Hauge ancestors were living.

In an act of kindness I will never forget, Ole Johan took the time to write a detailed local history for me, and I’ve translated it (see this post).

The beautiful Langedalen — view from the Hauge farm After giving me a tour of the area, Ole Johan delivered me to the Hauge farm itself, where one of my relatives, Arne Storlid, was waiting for us. Arne is the great-great grandson of Marta Jensdatter Hauge, who was the sister of my great-great-great grandpa Ole Jensen.

Pedigree of Ole Jensen Hauge

(To understand how this fits with my family tree, see Chart B on this page.)After figuring out how we were related, Arne and I met up with a cousin of the local historian — also named Ole Hauge! — who currently lives on one of the Hauge farms.

To my right are Ole Hauge (cousin of the local historian, Ole Johan Hauge) and Arne Storlid, my distant cousin I say Hauge farms (plural) because like most farms in Norway, Hauge was broken into several smaller landholdings (bruk). The one that my ancestor grew up on was called Det Jensane, but there was also Det Framme, Det Kauppane, Det Borte and Det Nære. Before about 1900, all of the houses were clustered together in what was called a klingetunet, with their respective farmland surrounding the homes.

This is what the klingetunet looked like before the houses were moved onto their own properties. This is a copy of a painting of the Hauge farms from the 1890s, courtesy of current resident, Ole Hauge.

Jensane — the bruk where my ancestor farmed

Property marker which stands at the place where three of the bruk come together Over coffee and cinnamon rolls, these gentlemen engaged me in a fascinating discussion of what life was like in the days of our common ancestors. I only wished my poor Norwegian comprehension didn’t get in the way!

But I am left with the overall impression that life in Langedalen hasn’t always been easy. While the land in the valley is relatively fertile, the fields are fairly small by American standards, and very few owed their own land in the 1800s — they were tenant farmers (husmenn). The prospect of large and mostly flat farmland that one could own outright must have been enticing enough to risk that journey across the Atlantic.

According to the bygdebok for Arna, my ancestor Ole had two other brothers — Mons and Johannes — who made that journey as well. But what became of them, I have yet to discover. Curiously, my own ancestor didn’t go directly to the U.S. The church records indicate that he left for Bergen in 1849. From there, we think he must have gone north to Førde (in Sunnfjord), perhaps looking for work. And I am grateful for that! If he hadn’t, he would never have met his future wife, my great-great-great grandma, Malene Olsdatter Bruland. It’s her story that I’ll turn to next.

Arne Storlid and I on the Hauge farm

[1] More precisely, Haus Clerical District (prestegjeld) had been divided into three parishes (sokn): Ådna, Haus, and Gjerstad. Our family was actually from Ådna sokn and lived on the Hauge farm located there – not the Hauge farm in Haus sokn. The relevant source is Lars Martinusson Ådna’s (1964) bygdebok — Haus i soga og segn. 17 3 : Ætt og æle : (ættarbok) Ådna sokn.

Hope you enjoyed this blog post. Feel free to subscribe!

-

O Christmas Tree

Christmas trees look even more out of place in Costa Rica than I do. Michael and I don’t have one at the AirBnB that we’ve rented, and it’s probably for the best. Christmas itself seems slightly out of place here.

Plastic tree with medium rare gringo Back in our Minnesota living room, our own Christmas tree is undoubtedly bone dry by now. I can already picture the trail of pine needles I’m going to make as I drag it to the curb. Even though I knew we’d be away for the holidays, I could hardly wait to get a tree. I bought one as soon as they popped up in front of the grocery store — with Mame’s “We Need a Little Christmas” playing on repeat in my head.

Our first stop on this trip was a small resort in Drake Bay perched high on a hill overlooking the Pacific. The resort is slightly worn around the edges, but the fact that it’s run by two gay Frenchmen ensures a certain level of fabulousness. Besides us, there were only two other groups in residence: a quiet couple from the U.S., and a trio from London consisting of a middle-aged woman and a rather elderly husband and wife.

The little airstrip at Drake Bay, Costa Rica The Frenchmen had arranged our daytrip into the wilds of Corcovado National Park. “Are you sure you don’t want a private tour?” one of our hosts had asked me. “No, we’re happy to share a guide,” I replied. And thus it came to pass that Michael and I would be trekking into the jungle with the three Londoners.

Our guide Jairo peppered us with jungle trivia throughout the day, some of which turned out to be slightly off-base (according to later Google searches). But what he may have lacked in precision, Jairo made up for in patience. The five tourists in his care turned out to be quite a handful. First, there were the two Minnesotans (that’s us!) who kept wandering off trail to take photos of every damned flower, toadstool, leaf and twig.

Fungus which caught my attention Then there was the elderly couple, Monika and Peter, who were quite fit for their age, but nonetheless struggled through the mucky jungle terrain. Peter was still attempting to regain his strength after a near-fatal bout of COVID and pneumonia this past year. Monika, a retired herbalist and acupuncturist, looked to be a touch older than her husband, and she flagged in the midday heat. But when engaged on a topic she enjoyed (e.g., the evils of processed foods), Monika would suddenly spring to life. Michael made the mistake of giving her his undivided attention, resulting in her chatting him up for the duration of the tour.

A discussion between Monika and Jairo about ficus leaves’ medicinal properties And then there was Louisa — Monika’s friend and former acupuncture client — who, as the day wore on, seemed increasingly likely to become some creature’s supper.

“You probably don’t want to go any closer than that,” Jairo would warn, and then Louisa would advance a couple yards towards the animal in question. If this were Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, I thought, Louisa was our Veruca Salt. “But I want a closeup of the viper!!”

We had been warned At the edge of a lagoon full of crocs, Louisa lobbed a stone into the water. “I just wanted to see if one would move!” she sputtered, as an irritated ranger escorted us out of that section of the park. Louisa protested that Jairo had done the same thing a moment earlier. The rest of us hadn’t seen Jairo do that, but then again Jairo’s capacity for discretion probably surpassed Louisa’s. Either way, the park ranger wasn’t having it.

The episode made me think of my mom’s older brother, Glenn. On a hike some 40 years ago, Uncle Glenn had scolded me for picking up a daddy long-legs spider by one of its spindly appendages. I was copying an older cousin who had done the same thing not five seconds before. “That’s no excuse,” Uncle Glenn told me. “How would you feel if someone did that to you?” How would I indeed. The lesson stuck, especially since my uncle had never spoken sharply to me before.

I met up with Uncle Glenn this past June in Madison, Wisconsin, right after he’d finished a workout at his CrossFit gym on Williamson Street. Frankly, I don’t think I’d survive more than 10 minutes of CrossFit, but my uncle barely looked winded. The gym is located right over the spot where my great-great-great grandparents, Johann Jacob and Elsbeth Reiner, built their home and blacksmith shop in the 1840s.

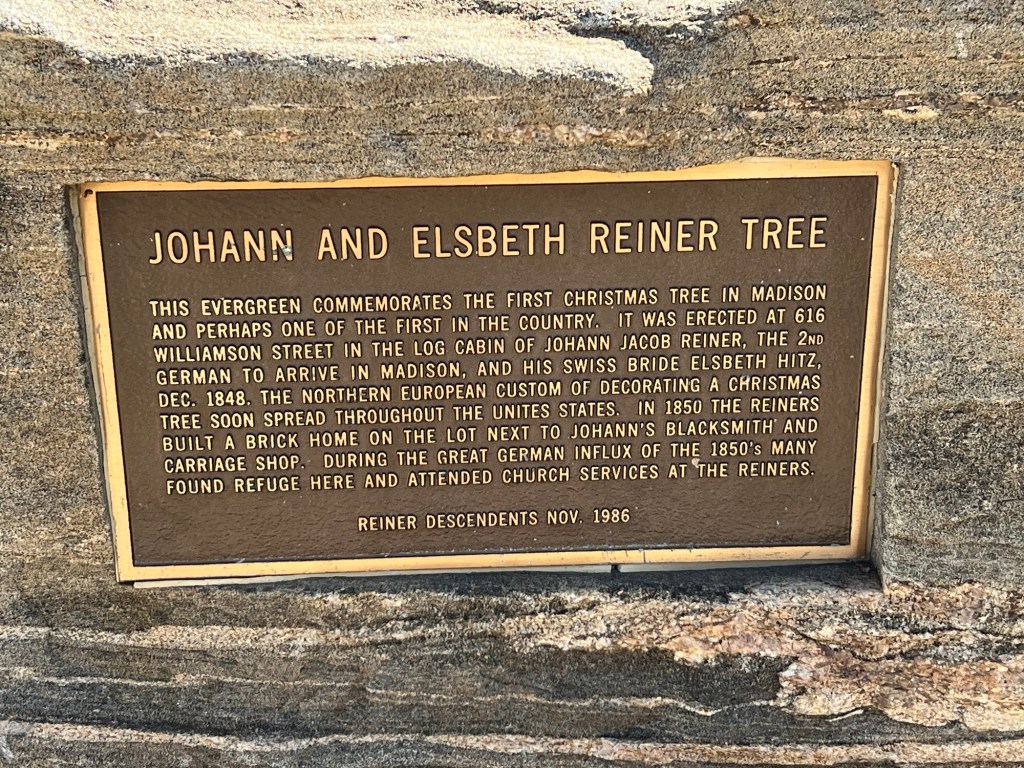

Glenn and I chatted as we walked my dog Spence around the neighborhood, stopping of course to visit the Reiner Tree. This is the evergreen that was planted to commemorate the Reiners’ footnote in Madison history. A plaque beside the tree describes J.J. and Elsbeth’s funny German custom of bringing a conifer indoors and decorating it for Christmas — a sight their Madison neighbors had never seen before.

Glenn & I at the Reiner Tree

The plaque at the Reiner Tree

In the Capitol rotunda, shortly before Capitol police asked us to take Spence outside

Former location of the Reiner home and blacksmith shop, now a CrossFit

A photo of the Reiner residence (courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society); the brick home (built in 1851) replaced an earlier log cabin It’s hard to imagine Christmas without Christmas trees, but they were virtually unheard of in America before 1850. It wasn’t until Queen Victoria and Prince Albert put one up in Windsor Castle in 1848 that the tradition started to take off in the English-speaking world. But the practice of bringing evergreens inside in December is much older, dating back to pagan celebrations of the winter solstice and its promise for rebirth.

Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children, gathered around the Christmas tree (source: this link) Intuitively, it makes sense to me that piney branches should hold promise for people in northern latitudes. While everything else looks dead, the boreal forest persists. Its roots spread in a more or less continuous circle across the global north — from Scandinavia through the whole of Russia, from Alaska to the shores of Labrador. Having a piece of this greenery indoors during winter’s darkest days is a reminder that, despite all appearances to the contrary, life will return.

O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum, we learn from all your beauty

O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum, we learn from all your beauty

Your bright green leaves with festive cheer, give hope and strength throughout the year

O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum, we learn from all your beauty

— translation of the third verse from “O Tannenbaum”

Here in Costa Rica, however, the lines between birth, death, and rebirth are not so stark. Everything is in constant flux, and the seasons are governed more by the coming and going of the monsoon rains. An evergreen doesn’t hold the same value in a place where things stay more or less green year round.

Jairo led our eccentric little group through a part of the jungle thick with towering ficus trees. Normally chatty, the five gringos grew quiet at the feet of these giants. “The roots of the ficus,” Jairo explained, “stretch out in every direction so that they touch all of the other ficus in the area. If one of the trees needs more nutrients, they pass those nutrients along to the one in need. If one is in trouble, the others come to its aid.”

Here was a different tree with a different lesson — one that I think each of us realized we needed to hear.

The roots of the ficus -

A tip of the hat to Britanno-American friendship

Everywhere I travelled over the past 10 days, I was reminded of the close and abiding ties between Great Britain and my home country. What might have started as a begrudging alliance between mother Britannia and her uncouth, rebellious child blossomed over time into a deep friendship. The progression of this relationship was laid out for me at various points in my journey.

In Worcester, for example, I learned that in 1786 the men who would become the second and third presidents of the United States paid a visit to Fort Royal Hill. The site had played a vital role in the English Civil War over a century earlier (1642-1651), and John Adams declared it “holy ground”, which all the English should visit in pilgrimage annually. Adams successfully negotiated the peace between Britain and her rebellious former colonies.

Flag from the Presidents’ Rooms at the Commandery in Worcester Adams’ travel companion — political rival and presidential successor, Thomas Jefferson — was similarly excited about visiting Worcester. A decade earlier he had penned those famous words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”, words which had been partly inspired by England’s Bill of Rights, authored by Worcester MP John Somers.

For a variety of cultural, linguistic, political and economic reasons, too numerous or obvious to mention here, this relationship strengthened over the decades (aside from a brief hiccup at the Canadian border during the War of 1812). One of the drivers of this bond has been the migration of British citizens to the United States.

Some of the earliest and most famous emigrants had their start from these steps, located in Plymouth According to one source, over 4.5 million people emigrated from Great Britain to the U.S. between 1820 and 1957, and I’d wager that well over half of all Americans have some British ancestry. I am aware of at least six of my direct ancestors who emigrated from England between 1845 and 1855, and I had the privilege of retracing some of their footsteps on this trip (for example, see this post and this post).

People, goods, and culture have flowed the other way, too, of course. And on multiple occasions in my travels, I was reminded of how ex-pat Americans have made their mark on Britain, from T.S. Elliot to Madonna. One of the first Americans to travel east across the Atlantic was the daughter of a Powhatan chief in Virginia. She made landfall close to the Mayflower Steps (pictured above) in the year 1616. She was called Amonute in her youth and later Rebecca Rolfe after her captors “encouraged” her to convert to Christianity. We know her as Pocahontas. She died just a year after arriving in England.

Two of America’s major humorists of the 19th century, Mark Twain and Charles F. Browne (aka Artemus Ward), spent time in Britain. Browne was so inspired by an 1866 visit to the Tower of London that he included it in one of his stories. Sadly, Browne fell ill and never made it home. Twain made several extended visits to England and became a beloved figure in London.

An easily overlooked panel about Browne at the Tower of London

Twain after receiving an honorary doctorate from Oxford It’s hard to separate the friendship of nations from the friendships of their leaders. This point was brought home to me during a visit to the Churchill War Rooms in London. The Allies’ success in the Second World War was due in part to the strong, personal relationship between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Churchill and Roosevelt meeting for the first time during the War (August 1941). In Newfoundland they signed the Atlantic Charter, a declaration of common principles between Britain and the United States. Three days later, Churchill telegraphed the Lord Privy Seal, Clement Attlee, “I am sure I have established warm and deep personal relations with our great friend.” (Photo displayed at the Churchill War Rooms) World War II was a bonding experience for ordinary Americans and Brits too, as over 2 million Americans passed through or were stationed in Britain during the final four years of the war. As I have written elsewhere (see this post), my maternal grandpa was one of those 2+ million. Visiting some of the spots where he was posted in England made me feel more connected both to him and to the country where he lived in the first half of 1944.

Stepping into St. Paul’s Cathedral yesterday, I was deeply moved to discover that there’s a chapel in one of the most prominent places in the sanctuary — directly behind the high altar — which “commemorates the common sacrifices of the British and American peoples during the Second World War and especially those American service men whose names are recorded in its roll of honour.”

The American Memorial Chapel, located in the apse of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Above the inscription is the book of Americans who lost their lives in Great Britain during the War, most of whom were airmen. One of the most endearing transatlantic friendships is captured in the letters between New York bibliophile Helene Hanff and London bookseller Frank Doel. Twenty years ago, my partner’s parents gifted me a copy of those letters, collected in Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road, and it quickly became a favorite of mine. I made a pilgrimage to the address from which Hanff was procuring her out-of-print books, only to find that a McDonald’s now stands in place of Marks & Co. bookshop. Ugh! The existence of a commemorative plaque takes away some of the sting.

And on a personal note, one of the best things to come of this journey was the opportunity to rekindle friendships with two of my old classmates from Kanazawa University, David and Sim. They opened their home to me, allowed me to make it a base for my adventures, and gave me personal tours of their beautiful city. They also spoiled me rotten with fantastic homemade meals, bottomless cups of coffee and tea, and my first taste of sticky toffee pudding. I hope that one day I can give them the same royal treatment on the other side of the pond.

My hosts – Sim, David and Harry – standing on the bridge over the River Thames that leads to Hampton Court Palace -

The Wells family of Worcester

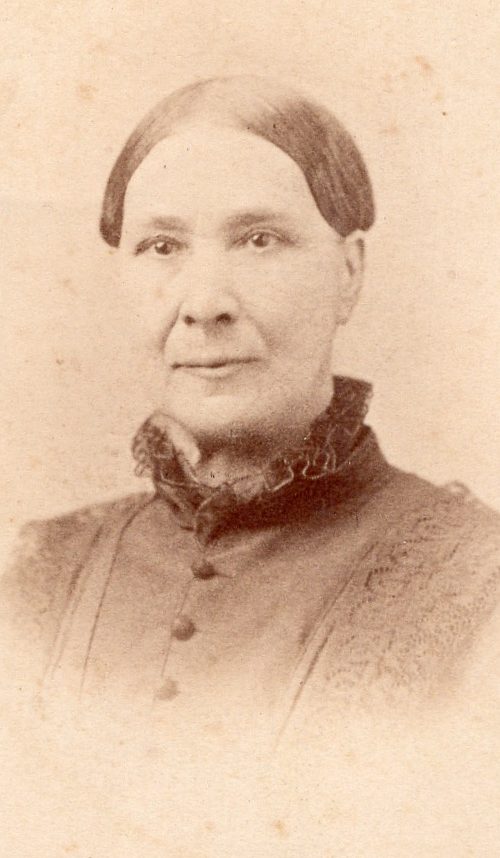

My grandmother’s grandmother Fannie Wells was born just north of Madison, Wisconsin in 1854, a few years after her parents Maria and William Wells had emigrated from Worcester, England. Fannie died in 1931, but she is remembered in my great-aunt Helen’s genealogy as a deeply spiritual person and “an immaculate housekeeper, [who] always placed a newspaper under the dinner plates of children.” She dressed well and “always looked quite prim without so much as a hair out of place.”[1] Fannie was the second of five known children born to Maria and William, and she would have been 10 years old when her father enlisted in the Union Army and never returned.

Fannie (Wells) Reiner, reprinted from p. 85 of Aunt Helen’s genealogy I attempt to retrace William Wells’ Civil War experiences in a separate blog post. Today, I’m in Worcester, wandering the streets where William and Maria once trod. I’m not the first descendant to do so. My great-aunt Helen Reed, my mother Beverly Rude, and a relative named JoAnn Hopper (a descendant of Maria and William’s son Albert) have all made separate pilgrimages to Worcester over the years.

Friar Street in Worcester Worcester is steeped in history, and coming here helps me imagine what Maria and William’s lives may have been like before they left in the 1840s. According to their 1845 marriage record, William’s occupation was a skinner.[2] And an entry on a ship manifest from the same year, which I believe belongs to the couple, lists both of their occupations as “leather dressers.” In other words, Maria and William, like thousands of their neighbours in Worcester, made their living from the manufacture of leather.

Dents built the first glove factory in Worcester. While this photo of their operations is from 1895, it is possible that William and Maria worked in one of the older buildings pictured. (Photo courtesy of Museums Worcester)

The Dents factory no longer stands in Worcester, but the building that housed Fownes Gloves (built in the 1880s) remains. The leather industry, particularly glove-making, was central to Worcester’s economy for centuries. According to this blog post by Museums Worcestershire manager Philippa Tinsley, the industry peaked between 1790 and 1820, “when half of all British gloves were made in Worcester. In the 1820s there were 150 manufacturers of leather gloves in Worcester and 30-40,000 people were estimated to be employed in the glove industry in Worcestershire and Herefordshire.”

Fownes Factory leather cutters (1890s), photo courtesy of Museums Worcestershire However, the English tax on imported gloves was lifted in 1826, resulting in an influx of cheaper imports. The effect was that “in Worcester, thirty thousand full-time jobs in 1825 [were] reduced to sixteen thousand in 1832, of which only just over three thousand were full-time.”[3] According to research by Museums Worcestershire, “following the disastrous 1820s, the two decades prior to mid-century were a period of uncertainty. Many manufacturers were bankrupted or voluntarily moved out of the glove trade.” And in the 15 years prior to the Wellses’ emigration, the number of glove manufacturers fell by about 50%. Believing that the leather industry was in freefall, Maria and William Wells may have felt they needed to seek a livelihood elsewhere.

But what was their work in Worcester like? When William and Maria Wells labored as leather dressers, the converting of animal hides into the fine leather used for gloves and other items was no small task. Prior to modern chemical processing and mechanization, glove-making required a great amount of time, resources, and skilled labor. David Nash, social history curator with Museums Worcestershire, explains (in this blog post):

“[The skins] are first cleaned and soaked in lime to remove hair and break down fats before being soaked in bark pits to tan the leather. This tanning process is essential to stop the skins from decaying. It also makes the flesh much more durable and gives the leather the traditional brown colouring that we are familiar with.”

Photo courtesy of Museums Worcestershire “For good gloves, the leather would need to be softened. Leather can be ‘misted’ and then ‘dressed’ with egg yolks which will permanently soften it without making it greasy. Leather for gloves might also be stained, and the colour fixed by boiling it with dye. After these processes, the skins are slowly dried out and stretched to achieve a finished state. Any remaining toughness is removed by drawing the leather firmly over a curved blade and the side that will sit against the wearer’s hand is then shaved with a paring knife in order to remove any roughness.”

Stretching of the leather; photo courtesy of Museums Worcestershire I reached out to Mr. Nash to better understand the industry and he generously offered to meet me at his museum’s off-site storage facility, where he is busy preparing a new exhibit on Worcester’s glove-making industry.

David Nash, demonstrating the kind of work that William Wells may have done Nash has an encyclopedic knowledge of the people and processes behind Worcester’s glove-making tradition. He explained that there were as many as 50 processes and individuals involved in the making of a glove from the animal being slaughtered to the glove being ready for sale. Processes ranged from the tanning, dressing, and cutting of the leather (see photos above) to the assembly, ironing, lining, and packaging of the gloves.

Here I am, trying to look like I know what I’m doing with this press. This is the type of press that would have been in use when Maria and William were working in the industry. Women and men each had roles to play, and, according to Nash, women were employed in the industry at a rate of 16 women to each man (although they made less money than the men).

Gendered occupations in the trade (photos courtesy of Museums Worcestershire) The end product was an exquisitely engineered article of clothing that every person would have owned — from farmhands to royalty — albeit in different quantities and levels of craftsmanship. To this day, in fact, the British royal family have worn gloves made in Worcester.

The team behind Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation gloves; photo courtesy of Museums Worcestershire While the final product may be glamorous, the making of gloves was traditionally a malodorous process. In fact, the stench of the tanneries in central Worcester led to their being moved to the west side of the River Severn in the 15th century (see this post). This was the area of town where the Wells family lived and attended church at St. Clement’s.

St. Clement’s Church on Henwick Road; the Welles lived just down the street at 89 Henwick According to Nash, many émigrés from Worcester continued the glove-making trade in the United States. Towns such as Gloversville, New York became home to skilled tradespeople from Worcester and other glove-making centers around the world.

To my knowledge, my ancestors left this craft behind when they emigrated. Maria and William bought a farm, raised dairy cattle, and pursued a life on what was then the American frontier. We have evidence, however, that William’s brother Josiah stayed in Worcester and continued working in the glove-making industry – an industry that persisted here until the 1970s.

The Wellses’ association with this highly skilled occupation is something that their descendants should be proud of. And as one of their descendants, I am also humbled by the sacrifices they made to secure a future for successive generations by leaving behind both the industry and the country they knew so well.

Maria Butler Wells Hastie with grandson George Gilbertson (reprinted from p. 90 of Aunt Helen’s genealogy) * * *

I want to thank Museums Worcestershire, particularly social history curator David Nash, for providing most of the information about glove-making in this post. Mr. Nash’s enthusiasm for this subject is infectious, and he has helped me appreciate my ancestors’ lives in a new way.

I also wish to thank my great-aunt Helen Reiner Reed, who originally kindled my love of family history and who continues to encourage my research.

From left: Aunt Hazel, Aunt Helen, Uncle Fran, my grandma Phyllis, and Aunt Alice — children of Albert and Jessie Reiner, grandchildren of Henry and Fannie (Wells) Reiner, and great-grandchildren of Maria and William Wells

[1] Reed, Helen A. Reiner. 1984. Ancestors and Descendants of Johann Jacob Reiner and Elsbeth Hitz and Allied Lines. The Anundsen Publishing Co.: Decorah, IA, p. 96.

[2] Ibid, p. 91.

[3] Redwood, Mike. 2016. Gloves and Glove-Making. Shire Publications: Oxford, UK, pp. 36-37.

-

How William Wells of Worcester ended up in Virginia’s bloody soil

My family left the Midwest and moved to Virginia when I was 13. At the time, I remember feeling like Virginia was another country. Its mountains, its speech patterns, its ties to a Confederate past – we were strangers in a strange land. But as we drove into the state after a stop in Washington D.C., my maternal grandma – wedged between my brother and me in the back of the car – reminded us that her side of the family had longstanding connections to the state. Her father’s maternal grandfather, William Wells, had died in Virginia serving the Union in the Civil War and was buried here.

In her sweet but persistent way, Grandma Phyllis suggested a field trip to find his grave. Maps were consulted (as this was in the days before GPS) and we made our way to Poplar Grove National Cemetery outside of Petersburg.

Five years later, I would be an undergraduate at the College of William and Mary, and I would pass this cemetery and its surrounding battlefields many times going back and forth between home and school. But I never stopped there again. The Civil War seemed so long ago, and as a young man I was more interested in a shiny future than a dusty past. My college, located beside the open-air museum of Colonial Williamsburg, felt all too rooted in yesteryear. I often rolled my eyes at Colonial Williamsburg’s employees, the “reenactors” who wandered Duke of Gloucester Street in their 18th century costumes, trying to engage passersby about the high price of candlesticks or whatnot.

But time and age have a way of changing us. As I approach my own half-century mark, I’ve begun to realize that “objects in mirror are closer than they appear”.

The distance between the end of the Civil War and the end of the Second World War is just 80 short years. Likewise, there’s a little less than 80 years between the end of WWII and today. In the span of a few generations, the United States has transformed from a backwards and largely agrarian post-colonial experiment – one at the brink of tearing itself apart over slavery – to a mighty postindustrial superpower (albeit still in danger of tearing itself apart). We can only imagine what the next 160 years will bring.

All of this is just to say that, as I’ve aged, I’ve gotten more curious about how Grandpa Wells ended up in that Civil War cemetery.

Fortunately, as I’ve mentioned in a prior post, I stand on the shoulders of others. In the 1980s, my grandma’s sister Helen conducted careful research into William Wells’s origins in England and his enlistment in the Union Army. The summary below is based on her work as well as some digging of my own:

In the early 1840s, William Wells and his bride Maria Butler were leatherworkers from Worcester in the West Midlands of England. They married in March of 1845 and, as far as I can tell, they almost immediately hopped a ship from Liverpool to New York. At the time of the 1850 U.S. Census, we find the couple – still without property or children – living with a farming family by the name of Stephenson in Dane County, Wisconsin. Had they headed straight for Wisconsin or did they live elsewhere for a while? Why Wisconsin? Did the Stephensons sponsor them? We have almost no information on the young Wellses, but it would appear that at this point, as Aunt Helen summarized in her genealogy, they “were not yet established in America”.1

The next decennial census and the 1860 county agricultural report paint a dramatically different picture: William and Maria now have four young children, 120 acres of land (12 of which is being actively farmed), and a good amount of wheat, corn, oats, potatoes and livestock. Their seven milk cows are producing $500 worth of butter per year. It would appear they were living the American Dream.

Aunt Helen again poses the pertinent commentary:

“We can only guess why on the 23rd of May 1864, 43 year old William Wells enlisted as a private in the 37th regiment of Wisconsin Volunteers leaving behind a farm, wife and five young children, the youngest only three and five years old. It is probable it was patriotism towards his new country or either the possibility of a draft of men under the age of 45 years or the enticement of the city of Madison offering an extra bounty over and above that of the federal government to men who enlisted in the Civil War.22

Whatever reasons William may have had for joining the Union Army, we can be sure of one thing: he could not have fully grasped what horrors awaited him.

Before I describe William’s brief and hellish military career, I need to set the scene. Throughout the 1850s, northern and southern states argued over the power of federal authority (especially the authority to regulate slavery) and the terms under which new states in the West would be admitted to the Union (e.g., as slave-holding or free states). Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 – with exactly zero Electoral College votes from the southern states – signaled to the South that they could no longer win this contest politically. Thus, seven states seceded and formed a new government in early 1861. Four other states later joined them. Neither side wanted war and neither could foresee the scale of the destruction to come. But what ensued was a series of the bloodiest battles that the world had experienced up to that point – battles whose names many of us know, even if we’ve forgotten the details from our high school history classes: Gettysburg, Chickamauga, Antietam, Shiloh…

One reason the Civil War was so deadly – and why it is sometimes called the first modern war – is the development of military technology in the form of long-range and quick loading rifles. Weaponry and tactics that we often associate with the First World War (e.g., repeater rifles, hand grenades, trench warfare) had their debut in the Civil War.4