-

The Burgess and Weeks families of Bristol and Somerset

My husband’s paternal line hails from Bristol, a major port city on the west side of England. Theodore Burgess (my husband’s great-great-grandfather) and Theodore’s father William Burgess said goodbye to Bristol on March 29th, 1852, climbing aboard a ship called Scurry with 127 other passengers. Scurry was bound for Port Phillip (Melbourne) and Sydney, Australia, and Theodore (19) and father William (57) are the final names listed on her manifest. Despite her name, Scurry didn’t drop anchor in Sydney Harbour until September 10th — after over five months at sea.

A world away from England, Theodore would go on to marry Clara Fanny Weeks, a young lady who grew up in the Somerset countryside. In Sydney, Theodore and Clara Fanny would have at least 10 children together (7 reaching adulthood), and Theodore would provide for the family as an omnibus driver. The family resided southwest of the city centre, in Darlington. Theodore and Clara Fanny’s eldest surviving son, Frederick Edwin (1858-1906), was my husband’s great-grandfather.

Horse-drawn omnibus at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, Australia (source: https://collection.powerhouse.com.au/object/207261) What prompted Theodore and William Burgess to sail for Australia is unknown, but it may have been a combination of economic and personal factors. Bristol’s population quintupled in the 19th century, and there was a shift away from certain traditional trades. Both Theodore and William were listed on Scurry‘s manifest as “moulders” (i.e., metalworkers), and Bristol’s copper and brass manufacture had been on the decline. In addition, William’s wife Ann had died in 1850 — only 54 years old. We can speculate that such a shake-up in the life of the family could have inspired thoughts of going abroad.

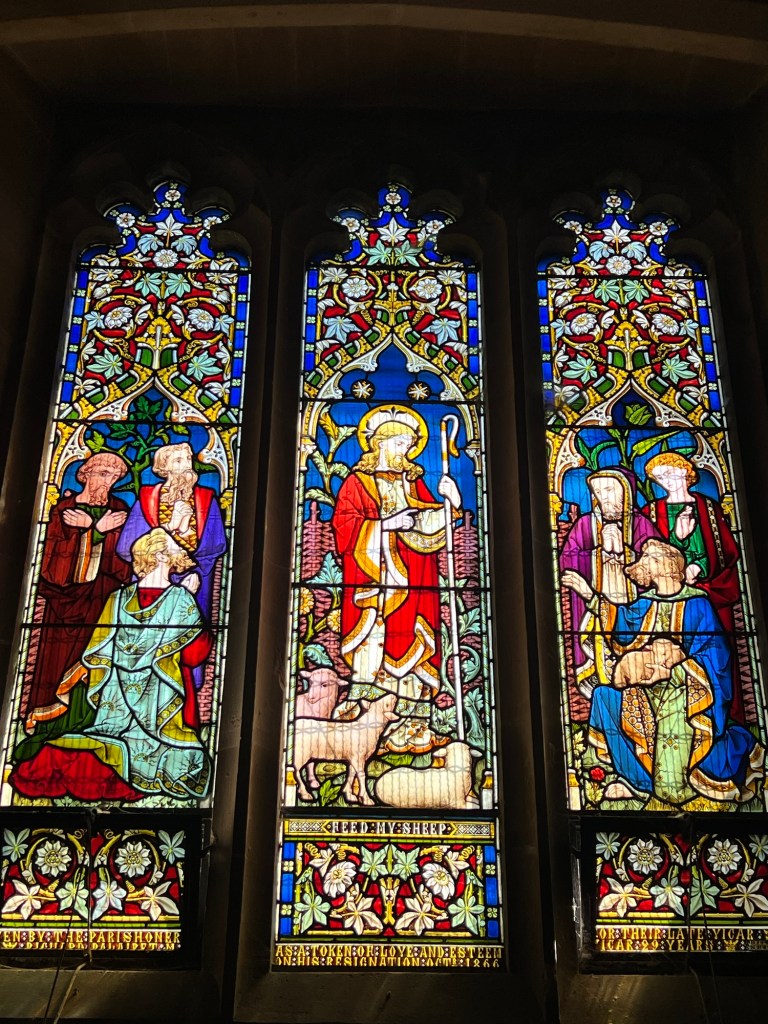

The church in Bristol where the Burgesses were members still stands. Affectionately called Pip ‘n’ Jay by the locals, the Church of St. Philip and St. Jacob claims to be the oldest place of Christian worship in Bristol. It is now home to an evangelical congregation, which has renamed the church Central.

After a lengthy negotiation, I convinced a cleaning lady at Central to allow me to take a look around the inside of the church. Sadly, the evangelical denomination is modernising some of the interior, but many of the original elements shine through.

St. Philip & St. Jacob (aka Pip ‘n’ Jay aka Central) According to the 1841 Census in England, the Burgesses lived on Jacob Street, which runs along the north side of the church and reappears on the other side of Temple Way (what is now the A4044). In the Census, William (then 45) is listed as a labourer, and the family’s oldest sons — twins George and Joseph (15) — are also employed. Joseph, like his father, is described as a labourer, and George is a “turner’s apprentice”. A “turner” describes someone who operates a lathe machine, suggesting again that the Burgesses were working in industry. Theodore was only five years old at the time of the Census.

The neighborhood where the Burgesses lived, like Bristol as a whole, is a hodgepodge of old and modern, grand and gritty Meanwhile, Theodore’s future wife Clara Fanny Weeks and her family had been living just 15 miles away in the little village of Hinton Charterhouse in Somerset. The family doesn’t appear in the 1841 Census because they were on board the Victoria, headed for Sydney Harbour. Alexander and Harriet Weeks, plus their four young girls Mary Ann, Clara Fanny, Emma Harriet and baby Annie, arrived into Sydney on October 24th of that year. The Weeks family took up residence not far from the Burgesses in the area we would now call Sydney’s “Inner West” (specifically Petersham and later Newtown).

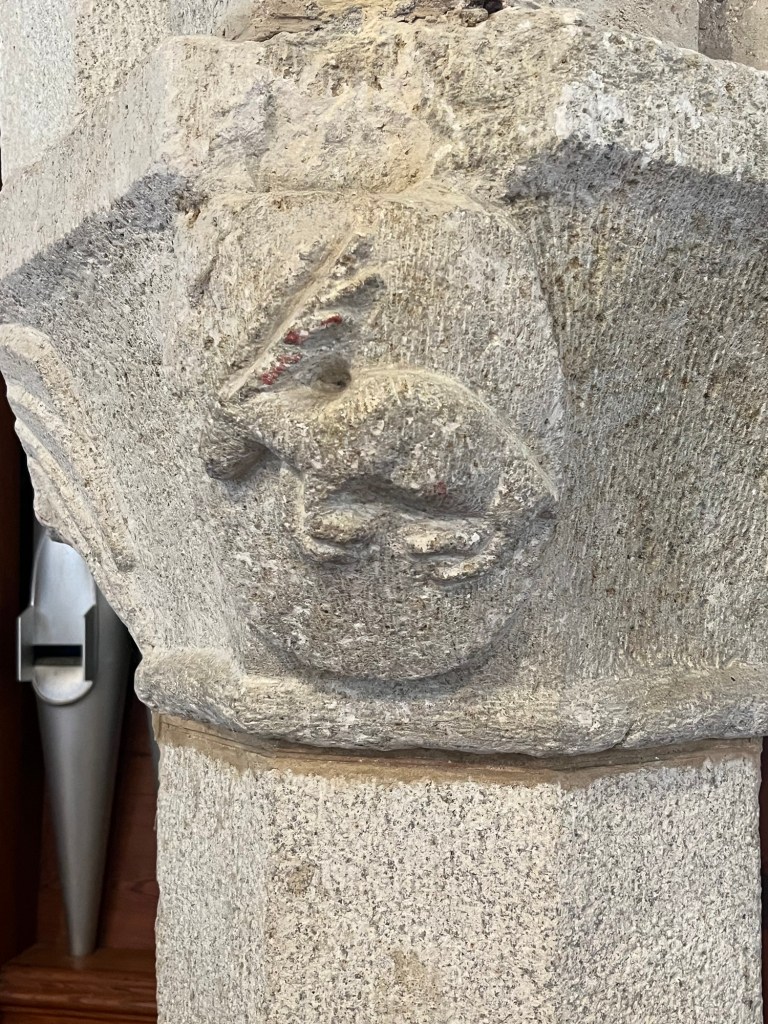

Hinton Charterhouse is located just five miles south of Bath. The church where Clara Fanny and her sisters were baptised, St. John the Baptist, dates from the 12th century. When I visited on Wednesday, I was pleasantly surprised to find the door unlocked, and I was able to wander around.

Church of St. John the Baptist in Hinton Charterhouse

Baptismal font at St. John the Baptist

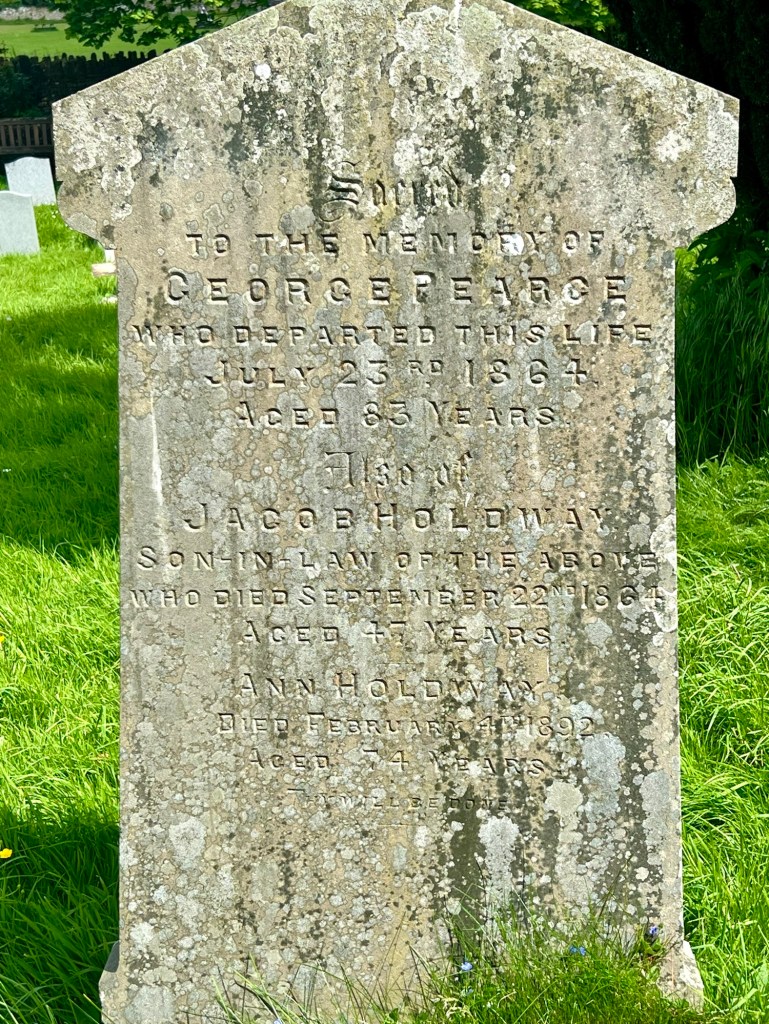

Facing the chancel from the nave in St. John the Baptist Walking around the churchyard, I didn’t see any graves with the surname Weeks, but I did see several graves with the surname Pearce, which was Harriet Weeks’ maiden name. A church volunteer in his 80s who was tending to some of the graves told me that people with the name Weeks live two villages to the south, in the community of Laverton.

Just one village south of Hinton Charterhouse is the extremely charming Norton Saint Philip. This is the village where Harriet Pearce was born and where she and Alexander Weeks wed in 1828. The church there, the Church of St. Philip and St. James, dates from the 14th century and still includes a number of ancient features.

The Church of St. Philip and St. James in Norton Saint Philip, Somerset

Scenes from Norton Saint Philip, Somerset I ended my genealogical adventure on Wednesday with a Bristol-made non-alcoholic beer at the George Inn in Norton Saint Philip. The George Inn claims to be the only tavern in England to continuously serve beer for over 700 years. Whether or not we can verify that claim, I’d like to think the Burgess-Weeks ancestors would approve.

-

Gene Smith’s Signal Corps service: Part 2 – England (February – July 1944)

On the morning February 28th, 1944, Cpl. Eugene Smith woke aboard the RMS Aquitania. He had heard the ship’s anti-aircraft guns fire a couple of times during the night but the word that morning was that it had just been a test. He and the rest of Company C took their turn in one of the aging ship’s grand diningrooms for the first of their two daily meals: watery oatmeal (again). After chow, Gene and a few of the guys headed up to deck for a smoke break, just in time to catch a glimpse of the northern coast of Ireland. A year ago he had been just a farm kid who had scarcely left the state of Wisconsin. Now he was Cpl. Smith and on his way to the European theater of the War.

After navigating the Firth of Clyde, the Aquitania docked at Greenock, Scotland. “I can still close my eyes and see the wonderful sight,” wrote Gene to his wife Phyllis back home. “The harbor was full of boats of all sizes, descriptions, colors and nations. It gave a fellow a sense of security with the battleships. And too there were planes flying overhead almost all the time. They were English ‘Spitfires’.”[1] Gene and his company stayed on board until the evening of the next day, disembarking shortly after dinner. “What a funny sensation,” wrote Gene in that same letter, “to put your feet on solid ground again!” Ironically, he felt seasick only after putting ashore. The men were directed to an overnight train which took them south to the town of Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk (East Anglia). The train was so crowded the men had little choice but to stay awake all night. They played cards to pass the time as the train rumbled south past Glasgow and the Scottish countryside.

At about nine or ten the next morning, the troops arrived into Bury St. Edmunds. From the station, the men were marched for about a mile towards the camp, each carrying roughly his own body weight in packs on their backs.

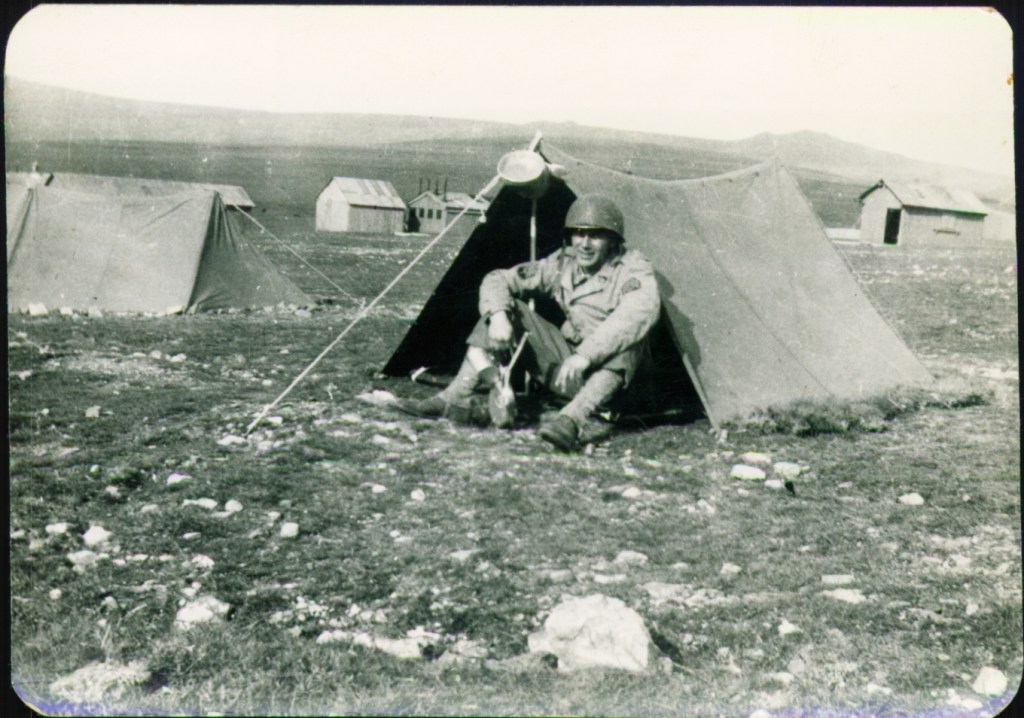

“It was all uphill but the thought of a bed and some comfort ahead kept us going. What a disappointment! It was in the middle of the winter and there were a bunch of tents staring us in the face. No heat, no light, muddy floors, no nothing but a tent and a bare Army cot. We had only one blanket – no two, but it still wasn’t nearly enough. We slept with our clothes on and shivered.”[2]

Some of Gene’s comrades in arms (Bury St. Edmunds, England, 1944) Conditions at the makeshift camp eventually improved after a few weeks, but Gene’s letter described great stretches of doing nothing interspersed with marching, training, and “detail” (i.e., grunt work). And amid what Gene felt was a “pointless, disgusting life”, there were also episodes of terror. The camp at Bury St. Edmunds was situated near a British airfield, and the men were often awakened by air raid sirens when the Germans bombed the area.

Gene described what that was like: “First a screeching siren went off that was enough alone to shatter a person’s nerves. Then all would be deathly quiet, and then another siren, and then you’d hear planes coming closer and the anti-aircraft getting louder and louder […]. Finally the planes [would be] going over with me lying on my cot shivering and praying for all I was worth.” No bombs fell on Gene’s camp, but he reported hearing many explode in the vicinity, and he “learned to identify German planes by ear as easy as an Englishman.”

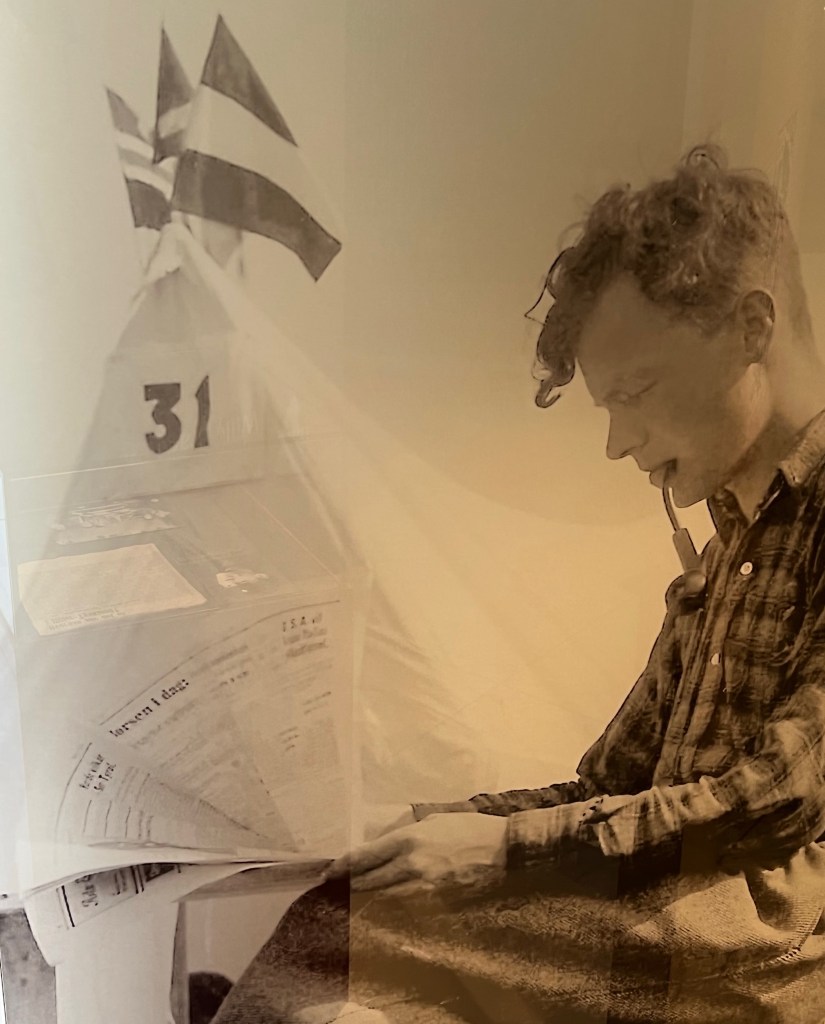

Gene trying to make the best of tent living (Bury St. Edmunds, England, 1944) After about two months in Bury St. Edmunds, the men were sent south to Burton Bradstock on the Dorset coast. Gene’s team camped out on a hill overlooking the valley and the little town. They were only there about a week, awaiting orders for their next assignment, but they welcomed the warmer coastal weather. Those orders came around April 15th, and they were moved to Bampton in Devon, which Gene described as “a one horse town back in the middle of nowheres”. In Bampton, the men were billeted on the second floor of a Methodist church, which turned out to be a less than ideal arrangement:

“Well I do remember the Sunday the minister came up and gave us hell because there was so much noise and cussing going on that it disturbed his ceremony. Another time one of the fellows saw a switch by the window and threw it to see what would happen; nothing did but in a short time someone came up and complained of not being able to use the pipe organ, and sure enough, throwing the switch fixed it.”

The old Methodist chapel in Bampton is now a private residence. Photo from my visit to Bampton on May 14, 2024. After only a week or so at Bampton, the men were reassigned to different work teams and sent out in small detachments. Gene and four or five other men were assigned to run a public address system for a network of American camps in the area, including in Plymouth, which was a port of embarkation on D-Day. As Gene explained in his letter, “It sure looked like a ringside seat to the invasion and we were pretty happy about it. We studied the equipment, set it up and took it down and experimented with it. Evenings we would take it around to different camps and play records over it or connect it up to a radio in our own camp.”

Gene (at left) and his fellow solders, location unknown The men were stationed in a park about three or four miles from Plymouth. They stayed in tents without modern conveniences, but Gene was warm and didn’t mind the rough living. And fortunately, they had a fairly permissive commanding officer who would give them passes to town when asked.

“As a result, I spent quite a bit of time in Plymouth. It might have been a nice place before the war but there were places ten blocks square that were bombed flat to the ground. There was hardly a single block that didn’t show evidence of bombing. One of my favorite spots to hang out was the ‘Hoe’. It is a park built on a cliff overlooking the harbor which leads into the channel. It was a beautiful sight to look out on the water and see ships as far as the horizon, thousands of them.”

A photo from my visit to the Hoe on May 11, 2024. Smeaton’s Tower is flanked by a row of flags of nations with relationships with the city

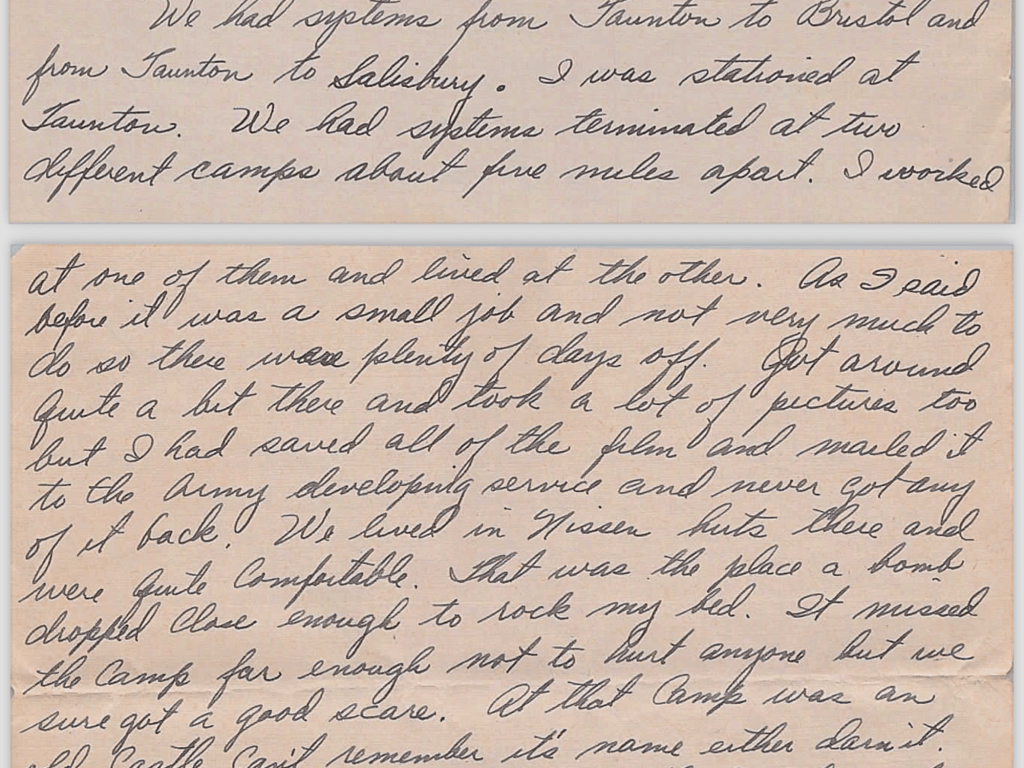

The Tinside Lido (outdoor pool), located just below Smeaton’s Tower on the Plymouth Hoe. My grandpa referred to this iconic pool in his letter. From late April until late June of 1944, Gene and his team were stationed near Taunton, where they set up communications systems between that town, Bristol, and Salisbury. They had systems terminating at two different camps about five miles apart; Gene worked at one of the camps and slept in a Nissen hut at the other. One night while he was there, a bomb fell close enough to the camp to rock Gene’s bed. But generally, those days in Taunton were easy going.

Excerpt from Gene’s May 21st, 1945 letter to Phyllis where he describes his time in Taunton

I believe that one of the Taunton camps my grandpa refers to in his letter was this one, on the grounds of the Hestercombe Gardens. His letter said the camp was near a castle, and Hestercombe House could certainly be mistaken for one. Only the ruins of one army building remain today, but this camp once served as a headquarters for US Army operations in the UK during the War. Big thanks to the staff at the Somerset Heritage Centre for pointing me to Hestercombe. And thanks to the staff at Hestercombe for allowing me to walk the grounds!

I believe this may be the other of the two camps my grandpa referred to. These Nissen huts are located a few miles from Hestercombe, across from the Cross Keys pub in Norton Fitzwarren. (Thanks to staff member Annie at Hestercombe Gardens for pointing the way!) According to the barman at Cross Keys, the huts were used as recently as the Iraq War. He said that tanks went in green and came out desert tan. After this point, “things happened faster,” according to Gene. Around June 25th, Gene and his team were sent to a camp at Bridestowe, just north of Plymouth, where units were brought in for processing before shipping across the Channel. After a couple monotonous days of drilling and classes, Gene and three other men were offered a temporary job running carrier and repeater systems near London. They leapt at the opportunity to get away from Bridestowe and headed to the job site – an airfield at Windsor.[3] Gene and his three companions ran a repeater station from a tent in the woods near the base. This set-up enabled communications between London and the airfield, and then to France via radio. The guys were there about a week before heading back to Bridestowe, but before they left Gene and one of his friends had an unfortunate encounter.

“Newk” and Gene (on right) The men had been taking it in turns at the repeater station; one or two worked the station while the others could go into town for food, etc. One evening when Gene and his buddy “Newk” (Arvon Newkirk) were in town, they had a few beers at a pub and were making their way back to their truck when they passed a dance hall that was letting out for the night. Twenty or so African American soldiers were coming out of the hall; they saw Gene and Newk and, according to Gene, demanded to know why they were there. In Gene’s recollection, the men were drunk and angry that two white soldiers dared to be in town that night. Just as U.S. Army regiments were strictly segregated in those days, American commanders had designated particular evenings in town as “for whites only” or “for coloreds only”. Gene and Newk were in town on the wrong night.

The situation escalated quickly. More African American soldiers arrived until there were over a hundred men in the street, according to Gene.

“So, Honey, right then for the first time in my life I found out what ‘mob spirit’ meant and I was on the short end of it. Newk and I did what little we could to defend ourselves but we didn’t have a chance. If we turned our faces one way we were hit on the other. In practically nothing flat we were in the gutter with about three inches of water (it had just stopped raining). God or a guardian angel or something must surely have been watching over us right then because just as I got to my feet all hostilities ceased. Newk was still down. A couple of colored officers, bless their souls, had gotten in the center with us somehow and their bars [jacket insignia] did the trick. They walked with us the remaining block to our truck and we took off.”[4]

In his letter to Phyllis, Gene used this incident to explain his negative attitude towards African Americans. But I have to wonder what attitudes my grandpa brought with him that evening and whether the incident may have confirmed beliefs he already held. My grandpa was a product of his times (as we all are), and the decades leading up to and including the Second World War were an especially fraught period in American race relations. We only have my grandpa’s version of events that evening; there might be more to this story.*

Gene’s detachment returned to Bridestowe around July 5th and stayed there for the next two weeks. The company was then sent to a marshaling area near Southampton where they awaited transport to Normandy. They didn’t have to wait long. The Allies had managed to secure a toehold in France but needed Signal Corps teams to coordinate their actions. The time had come for the 3110th Signal Service Battalion to do their duty on the other side of the Channel.

***

This story will continue in another post that has not yet been drafted. Please stay tuned.

To revisit the first part of Gene’s military career, see this post.

***

A memorial in Bath Abbey to the British-U.S. alliance during the War

[1] Letter to Phyllis dated May 21, 1945.

[2] Ibid.

[3] According to Leonard Cizewski’s website, a detachment of men were sent to an airbase in Middle Wallop. This might be the location Gene meant (instead of Windsor) because he describes the town of Winchester as being roughly 15 miles away.

[4] Letter to Phyllis dated May 29, 1945 (a continuation of a summary of his time overseas that Gene started in a letter the prior week).

* It’s tempting to gloss over episodes like this because they complicate or contradict a picture we have in our heads about our loved ones. Family histories are as susceptible (if not more susceptible) to selective memory as national histories are. Certainly, America’s “Greatest Generation” was self-sacrificing, a generation of men and women more capable of keeping the country’s individualistic impulses in check — at least compared to the generations that followed. But they were also raised in an environment where essentialist and supremacist notions of race, class, gender, and sexuality often went unquestioned. It’s easy to lionize or demonize this generation, depending on one’s agenda. But an honest attempt to understand history on history’s terms requires us to hold multiple (and sometimes contradictory) perspectives at the same time.

-

Gene Smith’s Signal Corps service: Part 1 – Camp Crowder and Camp Wood (March 1943 – February 1944)

My grandma Phyllis described in a letter the heartbreaking moment when she and the family dropped my grandpa Gene off at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. They wandered the premises for about two hours, watching some recruits do target practice and hoping they might catch a glimpse of Gene.

“When we got back to the car frozen stiff your mom said, ‘I don’t want to stay here any longer and I don’t want to go either.’ I guess that was the way we all felt, Darling.” About 60 miles away from the Smiths’ home in Fort Atkinson, the family picked up a hitchhiking solider from Ohio who was headed north. Gene’s dad Frank insisted on bringing the boy home and feeding him lunch. “It was an awfully funny feeling having him there, Darling, just after you had left. I don’t know whether it made things better or worse.” That evening Frank drove the soldier to a local diner and made sure he got a ride heading in the right direction.[1]

Meanwhile, Private Smith was trying to adjust to Army life. His first few days were packed with a series of physical and mental exams, filling out forms, getting a uniform and his first regulation “high and tight” haircut, receiving inoculations, and shipping home any last vestiges of his civilian life. On Day 2, the recruits had a compulsory meeting called “The Articles of War” where they learned how the chain of command works in a wartime military. Gene described this meeting to Phyllis as the one where “the law is laid down.” Mornings started at 5:45, and by 6 am the recruits were expected to have gotten out of bed, dressed, washed, shaved, brushed their teeth, made their bunk, and reported to roll call. But as Gene explained to Phyllis in one of his letters, “Don’t take it too serious tho Darling because none of us new fellows have been able to do it yet. Lucky me, I can shave in the evening and it looks just as good in the morning.”[2]

Fort Sheridan, Illinois (photo source) At the end of the week at Fort Sheridan, Gene and 102 other fresh recruits donned their new uniforms, packed their bags, and were marched to the station to board a southbound train. After connections in Chicago and St. Louis and a sleepless night (there were no sleeping compartments), the boys found themselves staring out the train windows at a bleak Missouri landscape. “The hardest part of the trip was that I couldn’t keep my mind off you for even five minutes. Lonesomeness for you is something I just can’t knock down, Darling.”[3]

Arriving at Camp Crowder in Neosho, Missouri, Gene and his fellow recruits began the four-week basic training program (“boot camp”). It took him a while to acclimate to the Army rhythms and terminology. As he explained to Phyllis,

“If you get a chance to study up on anything pertaining to Army organization it probably will make my letters much more understandable because I haven’t the time to explain everything. And it’s impossible to be here and write to you without using Army terms. ‘Army’ is the only thing I’ve seen, heard, felt or any other sense for over a week now. (Except my lonesomeness for you, and most of the time I’m so busy jumping to someone’s orders that I don’t even have time for that.) Darling, it’s impossible to put into words the difference between this and civilian life. I feel as if I’m a different person in a different world. And I’ll be glad when I can get back to the other one. You’re there, Darling.”[4]

One of the Army acronyms that Gene learned on day one was “KP” – kitchen patrol. He and a few other recruits were singled out to work in the kitchens that first night. On another day his first week he got in trouble for not having his shoes lined up precisely 3 inches from his bunk at morning inspection. More KP. And the training was physically grueling. The men were run through obstacle courses, sent on long hikes in the surrounding countryside with heavy packs, and marched around camp in formation. Then there were the various instructional periods in classrooms or outside with rifles. The days felt endless, and on top of this Gene had caught what the recruits called the “Crowder croup” – a cough that wouldn’t let up.

“It seems that all the fellows have it. It’s a terrible deep cough and you’re spitting up slugs all the time. My nose has been running continually since yesterday morning. You should be in a large classroom or one of these instruction movies where there are three to five hundred fellows in a room. You can’t hear anything for the coughing on all sides of you.”[5]

Photo reprinted from p. 58 of Jeremy P. Amick’s (2019) Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC. But basic training wasn’t a completely terrible experience for Gene. He was starting to get a sense of who he was, what he was made of:

“Here men are men, Darling, in an undiluted form. They cuss and talk just exactly as they feel. Here you see fellows as they really are because many things are so darn trying and there’s no backing out, flinching or backtalk of any sort, and it sure shows up the guys in their natural color. In analyzing my own emotions and actions here and comparing them (to myself) with the other fellows I’m quite surprised. I’m an entirely different person than I thought I was. I didn’t realize I’m quiet and so darn conservative, Darling. That was the most surprising thing.”[6]

When Gene finished basic training on April 17th, he would have a choice: apply for Officer Candidate School or receive more technical training. He knew that the former would be the pathway to higher ranks as a commissioned officer, but Gene was thinking further ahead, particularly of a future career in communications. “Which would do me the most good?” he asked Phyllis in one of his letters. We don’t know how she replied to that question, but ultimately Gene decided to follow his heart and pursue advanced technical training.

Camp Crowder, it turns out, was an ideal place to do that. Although originally intended to be a joint training facility for the infantry and the Signal Corps, by 1942 Camp Crowder was exclusively a Signal Corps training replacement center[7]. Crowder offered a number of specialty courses and programs after boot camp. Gene sat the test for the radio corps and did well (40 of 50 questions right) but was assigned to the telephone corps. Initially, he was disappointed but then found out that only two in his squadron of 103 recruits got into the radio corps. Over 90 of the recruits did not get into either – they were classified as truck drivers, messengers, and other auxiliary staff.

July 4, 1943 at Camp Crowder. (Photo reprinted from p. 42 of Jeremy P. Amick’s (2019) Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.) Gene’s days were a combination of drilling and schooling, and by all accounts he excelled. He was promoted to corporal after only a few weeks at Crowder. Here is a typical day as described to his parents in a letter:

“Up out of bed at nine o’clock. Breakfast at 9:45. Infantry drill from 10:45 to 11:45. Then if we don’t have any extra duty we are free until 2:45 when we eat dinner. At 3:45 we go to school. In school we have classes for 50 minutes and then a 10 minute break for a smoke or anything we want to do. [This repeats] until 8:00 when we come back here for supper. At 9:00 we are back in school and we get out again at midnight. The lights in the barracks go out at one o’clock and here in the dayroom they are on until two so we can write. But usually a guy is so darn tired that he doesn’t care to write at all.”[8]

After a few weeks, Gene’s schedule would shift back to days (i.e., up at 5 am, stand in formation for reveille at 5:15, breakfast at 6, in class by 7…), and it would alternate every other pay period. In total, the instructional period for the telephone corps was supposed to be 26 weeks but Gene was able to skip the first four. Sometimes after classes were done for the day, Gene and his group were sent out on “night maneuvers”, simulating telephone carrier duties in the field. They learned how to set up and troubleshoot switchboards in all manner of terrain and weather conditions.

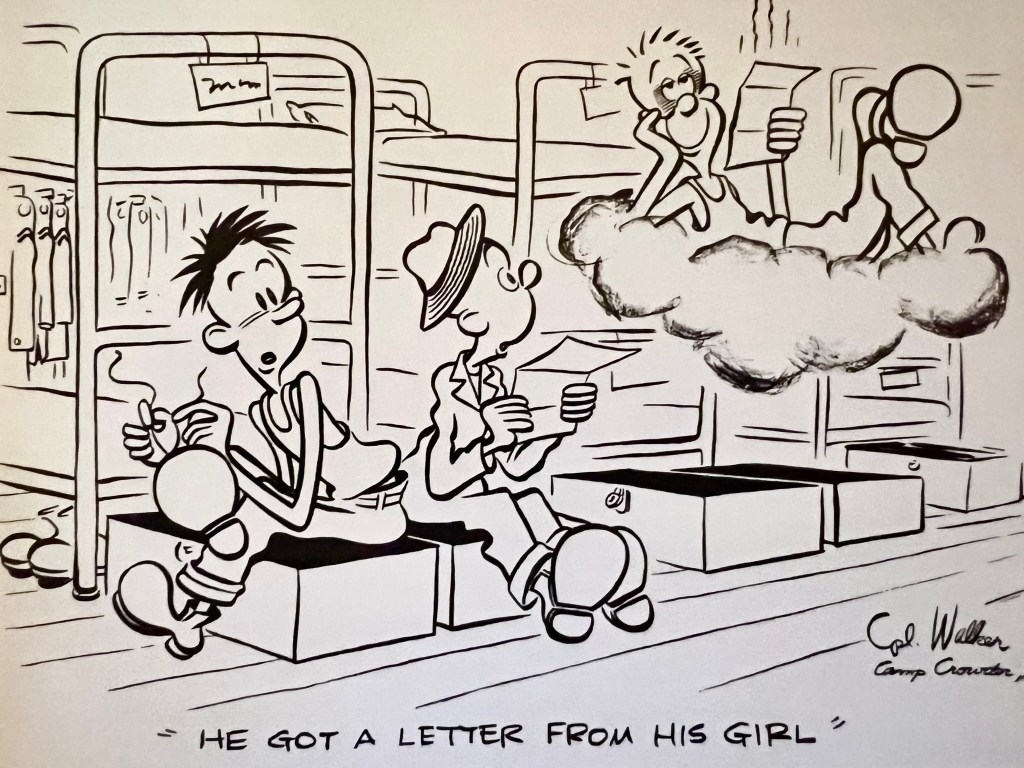

April and May of 1943 were particularly rainy. One of the barracks got flooded, and a young soldier by the name of Mort Walker made light of the dismal situation through a series of humorous drawings. Walker’s experiences at Crowder inspired “Camp Swampy”, the setting of a comic strip he published for decades – Beetle Bailey.[9]

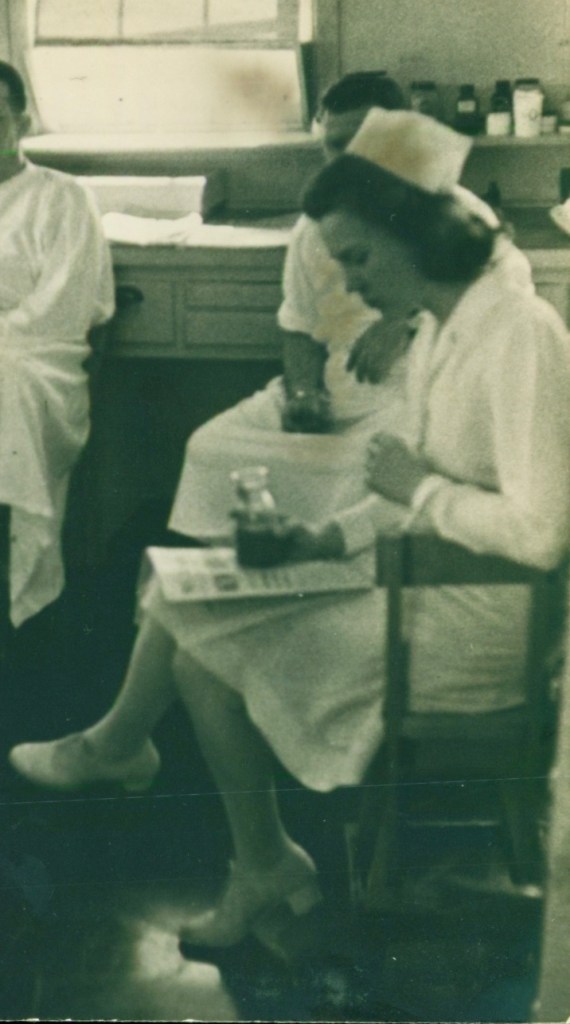

An early cartoon by Mort Walker, depicting life at Camp Crowder (reprinted from p. 53 of Jeremy P. Amick’s (2019) Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.) Gene’s major solace were the letters he received from the family back home and especially Phyllis. The two of them shared moment-by-moment accounts of their days and endlessly planned how they might be able to meet up in person. In May, Phyllis managed to secure a break from her duties at St. Mary’s Hospital and arranged a visit to Missouri, arriving by train on May 23rd. She stayed at a boardinghouse in Neosho and met up with Gene as much as his schedule would allow. They went out on dates and had a picnic one day, enjoying each other’s company and talking about how their future might unfold. Gene suggested that they get married right then and there, and Phyllis agreed. In a rush of excitement, they called Phyllis’s parents to get their permission. To their surprise, Al and Jessie Reiner did not like the idea. They told Phyllis to come home, and dutifully, on June 2nd she did.

Phyllis at St. Mary’s Back in Madison that summer, Phyllis came down with a serious respiratory illness. She worried that her tuberculosis had returned. She was attended by two different doctors at St. Mary’s who gave her conflicting opinions about what looked like a spot on her lung in an X-ray. Meanwhile, she was feeling conflicted about her future. In a letter dated July 16th, 1943, Phyllis wrote to Gene: “If I am perfectly alright, I don’t know whether I should continue nursing or whether I should go to Missouri and be my Darling’s wife. What is best to do, Darling?” After a couple of weeks in the hospital, Phyllis received the “all clear” from her doctors, and she decided she would quit school and join Gene in Missouri. When she went to turn in her books, one the sisters at St. Mary’s talked her out of it. She wrote Gene on July 21st, telling him she’d be going back to school on August 4th. And then, to everyone’s surprise, Phyllis showed up on Gene’s doorstep on July 23rd.

The couple arranged to get married at Camp Crowder’s chapel on Saturday, August 7th. But there was a hitch in that plan: when Phyllis went into town to apply for a marriage license on Thursday, August 5th, she was informed that a new law had gone into effect requiring the applicant to wait three days to receive the license. Three days meant Sunday, and the court offices would be closed, but the recorder of deeds told Phyllis to call his home on Sunday morning and he’d fetch the license for them from his office. He said he’d be home all day. So, they rearranged their plans to marry at the chapel on Sunday at 2:30 pm, and at 11 am that day, after getting herself dressed and ready, Phyllis phoned the recorder’s home. The person who answered said that the recorder had left to visit his son in the countryside, that he had waited until about 10 am but figured they weren’t coming. Phyllis was distraught. She called the recorder’s son’s home, but the recorder hadn’t arrived there yet. She tried to call Gene who was still at camp but was told there was no Eugene R. Smith there, only a Eugene F. Smith. In a frenzy, she hopped on a bus to camp, found Gene, and they tried to phone the recorder again at his son’s house. This time they got him. The recorder told them to go to the Justice of the Peace, who would be able to open the recorder’s office and get the license. They raced to the Justice’s office, but he had left five minutes earlier and couldn’t be found. They had to call off the 2:30 pm wedding. Gene and Phyllis didn’t catch up with the Justice until 7 o’clock that evening.

Gene and Phyl’s plans for a picture-perfect wedding were dashed, but after hours of scrambling they finally had the marriage license in hand. Their best man and bridesmaid had gamely stuck it out with them through a frantic afternoon, and the best man was due to ship out any day. So they thought, why wait? They asked the Justice to marry them on the spot, which he did. As Gene described it in a letter home, “It was the most exciting, most disgusting, most wonderful day I’ve ever lived.”

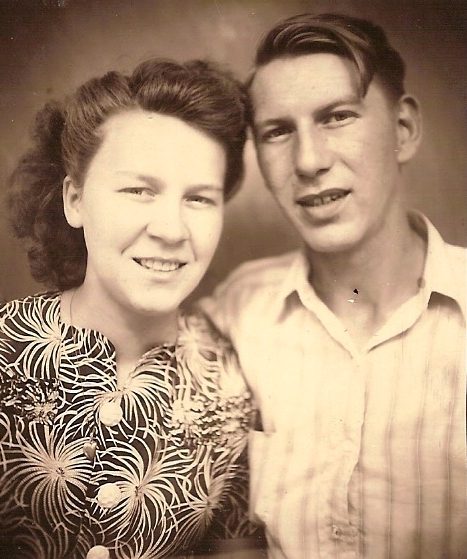

August 8th, 1943 – Phyllis and Gene get hitched

Gene and Phyllis (at left) with their patient bridesmaid and best man As a married couple, Gene and Phyllis were entitled to live off base. They moved into a simple little cabin a few blocks from the Camp Crowder gate, and Gene had to get up at 3:30 am to catch the bus into camp to be on time for reveille at 5 am. Phyllis got a part-time job as a waitress, and by the end of August she had found a position as a dental assistant at Crowder. The newlyweds spent as much time together as their schedules would allow. Typically, Gene would come back to the cabin by 8:30 pm, but on at least one occasion he was stationed “on bivouac” at his school building, operating a repeater terminal[10] and sleeping on the floor. He typed one of his letters home to his parents on a teletype machine while camped out at school.

On October 26th, Gene took his final exam and concluded his schooling at Crowder. He got his report card on the 29th and within minutes received his “shipping orders”: the next day he and three others from his group would join the 3110th Signal Service battalion, Company C. But what exactly that meant was not yet clear. In the short term, he was assigned to a detail at Crowder and would need to sleep on base except on nights he had express permission to leave. Gene suspected his group would be sent elsewhere for field training but when and where that would be he could only guess. He and Phyllis managed to obtain a two-day furlough in November, making a quick visit to the Smiths in Fort Atkinson. Then it was back to work in Missouri and back to waiting for news.

Gene on furlough That news finally came in mid-December – Gene was heading out, destination unknown. Within a few days, the couple packed up their little home in Neosho, Phyllis gave notice at the dental office, and they celebrated an early Christmas, knowing that they would likely not see each other on the day. Phyllis traveled home to Wisconsin, while Gene boarded a troop train. His train took an intentionally roundabout path, and the men were forbidden from sending messages en route, which could disclose information about the large troop movement. Once settled, Gene called Phyllis and told her his exact location: Camp Charles Wood in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The connection was poor and the two couldn’t hear each other, but Gene managed to communicate to Phyllis through the operator that he would have the New Year’s weekend off and that she should check the train schedules and come join him. She did just that, and on New Year’s Day the pair enjoyed sightseeing in New York City – about an hour and half away from Camp Wood by train. Gene reported to duty on Monday the 3rd and Phyllis took the long train trip home.

Two weeks later, Gene managed a brief visit to Wisconsin and back. He knew his team could be shipped out at any time, so he took this final opportunity to see Phyllis, his parents, and his sisters Shirley and Ruthie. I believe this photo may have been taken during that furlough:

Once Gene got back to New Jersey, his letters became more cryptic. He and his team were sent on assignments in the area, received tactical training using gas masks, and learned how to operate “Tommy” – the Thompson submachine gun. But Gene couldn’t disclose much, and starting on February 18th, his letters had to pass the censor before being mailed. He was at least able to tell Phyllis that he would be out of communication for a while, and not to worry about that.

February 8th, 1944, Camp Wood, New Jersey. Telephone Carrier and Repeater (GN) Team, Company C, 3110th Signal Service Battalion. Gene is the 2nd man from the right in the 3rd row from the bottom. It turns out that Gene and his team had left Camp Wood on February 14th, 1944 and stayed for six days at the point of embarkation, Camp Shanks, New York. Their unit and about 8,500 other soldiers[11] then took ferries to New York City and boarded the British vessel RMS Aquitania. On board, rumors circulated about where the ship was headed. As Gene later described in a letter, “We were pretty sure it was to Europe but you know how rumors are and there were very recent dates on the walls in pencil [listing] Pacific ports.” About two days before reaching their destination, the troops were told: they would be coming ashore in Britain.[12]

Cpl. Smith was about to get what he later called “a ringside seat” to the invasion of Europe.

* * *

To continue this story sequentially, you can read about Gene’s wartime service in England during the spring and early summer of 1944.

To go back and read about the events leading up to Gene’s enlistment, you can follow this link.

[1] Letter from Phyllis to Gene dated March 25, 1943.

[2] The details from Gene’s letters home closely match the Army’s own description of what new recruits could expect, as seen in this War Department training film from 1944: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85g4BKgrh0E.

[3] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated March 21, 1943.

[4] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated March 25, 1943.

[5] Letter from Gene to Phyllis dated April 2, 1943.

[6] Ibid

[7] Amick, Jeremy P. 2019. Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.

[8] Letter from Gene to Vina and Frank Smith dated April 23, 1943.

[9] See pp. 52-53 in Jeremy P. Amick’s (2019) Images of America: Camp Crowder. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, SC.

[10] In a letter to his mother-in-law Jessie Reiner dated October 26, 1943, Gene explained that “there are two general types of apparatus, carrier equipment and repeater equipment. The carrier is a sort of small radio transmitting station. Its purpose is to combine telephone conversations to high frequency electric currents and send a number of these combinations over one telephone line thereby reducing the cost of material, installation and maintenance of lines. They also have provisions for receiving and separating these frequencies and conversations. The repeaters are ‘step up’ stations, so to speak between the carrier terminals. They do much the same job as a pumping station in a city water system. It’s just a matter of increasing the pressure so it will carry to the place where it is to be used.”

For more insight into how these teams operated in the field, these Signal Corps training films are helpful: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kz-yytNbOyc and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LACLE6YTV28.

[11] Leonard Cizewski’s website chronicling his father’s wartime service reports that the number on board may have been closer to 12,000 (http://www.ibiblio.org/cizewski/felixa/deployment/unit.html).

[12] Gene was able to relay these details to Phyllis once the War had ended in Europe – specifically, in his letter dated May 21, 1945.

-

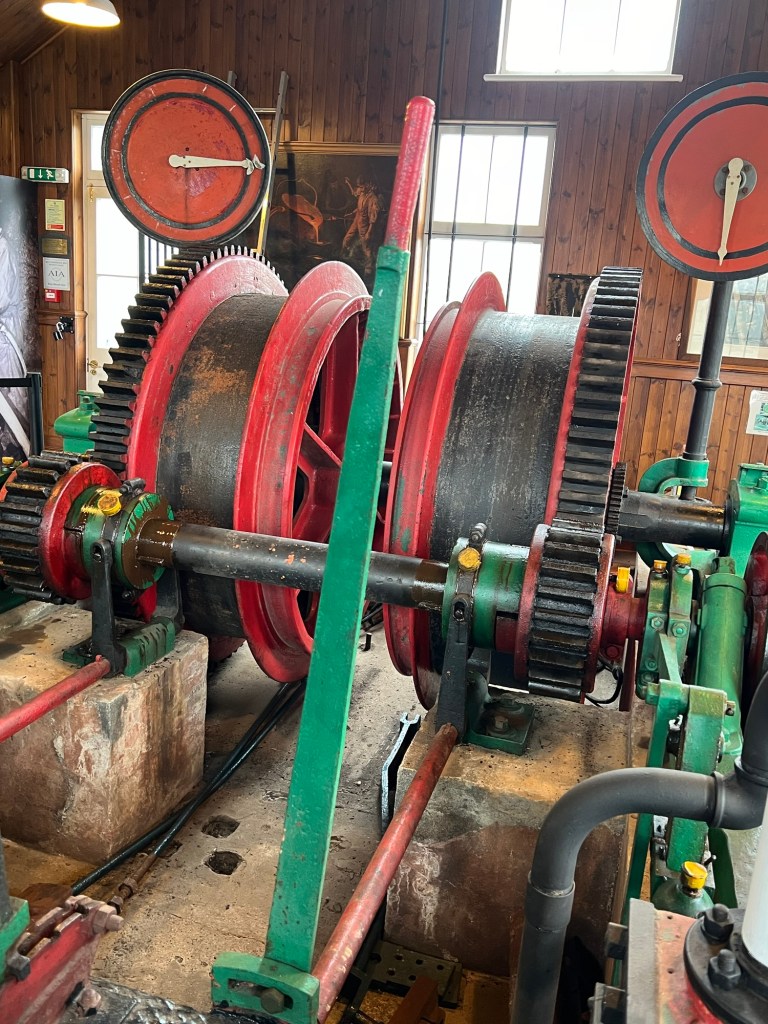

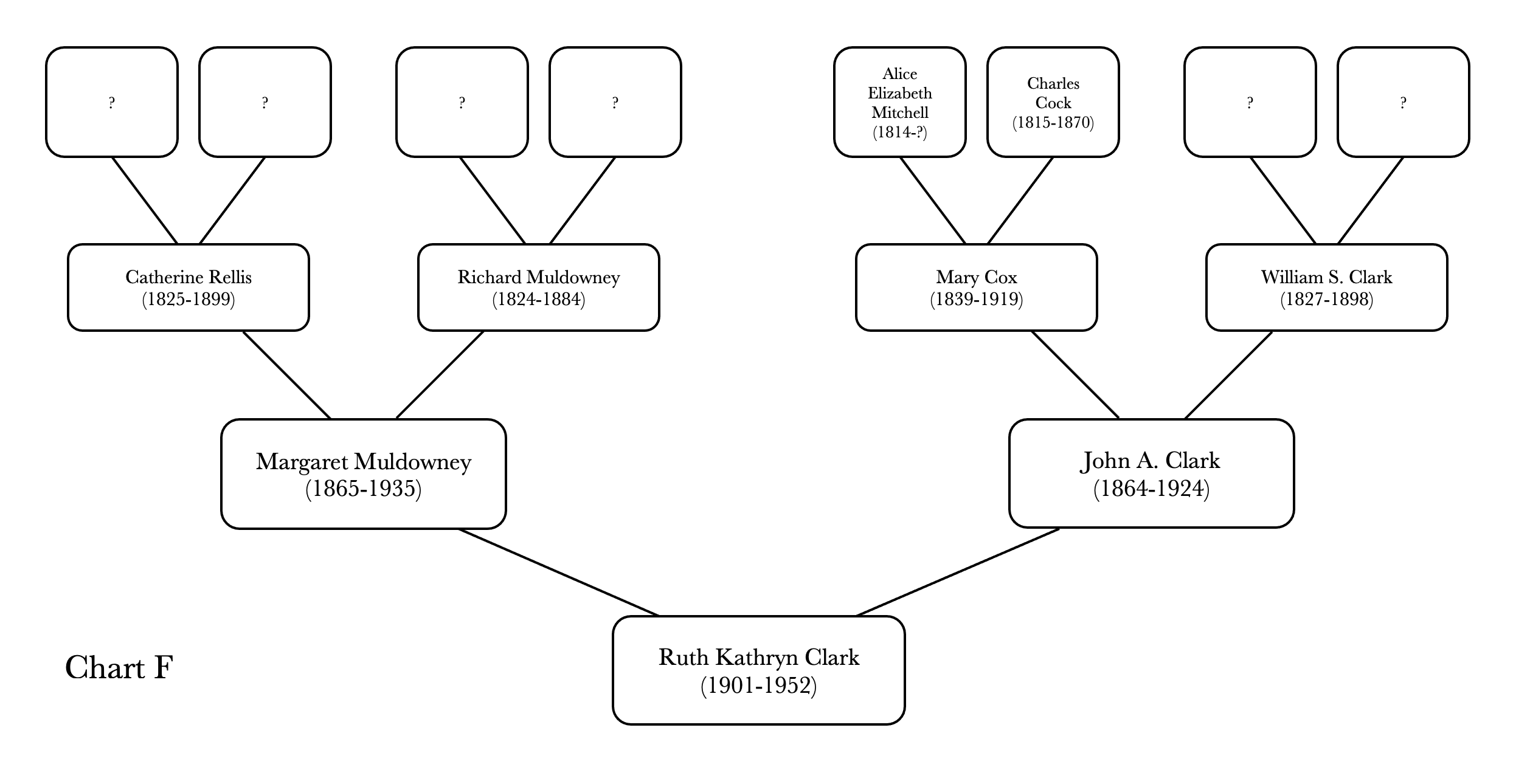

A journey down a genealogical mineshaft

A few years before my grandma Barbara Jean (Kaufman) Rude died, I started asking her questions about her childhood, her parents, and what she could remember of her grandparents. Although my grandma’s mind was sharp, the details were murky when she spoke about her mother’s parents, John and Margaret Clark.

There are a few good reasons for the murkiness. First, Grandma’s mother Ruth left home and when she was only 17 or 18 and moved a hundred miles away – from the town of Adell in Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, south to Edgerton in Rock County, Wisconsin. This was a considerable distance in the 1910s. Ruth’s father John died just a few years later, in 1924. This was two years before my grandma was born, so she never got to meet him. Finally, I got the impression that Ruth didn’t get along well with her mother Margaret. In point of fact, even though my grandma was nine years old when Grandma Margaret died, she couldn’t remember meeting her. She could only remember her mother Ruth saying that Grandma Margaret was “nuttier than a fruitcake”.

Margaret and John Clark (my paternal grandma’s maternal grandparents), Adell, Wisconsin, early 1920s It was little surprise then that when I asked my grandma about her great-grandparents – particularly her grandpa John Clark’s parents – she was at a complete loss.

I knew that John and Margaret Clark had moved to Adell from Highland, Wisconsin (in Iowa County), and that’s also where Margaret’s parents – the Muldowneys – had lived. But what about John’s family? Other than a few facts I could glean from John’s obituary, I had precious little to go on. Out of the blue, a distant relative on this side of the family sent me some details about John’s parents, information that had supposedly been provided to her by a genealogist. But the facts didn’t line up, and those red herrings threw me off the trail for quite some time.

Eventually, I reached out to the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, and a kind soul there helped me track down records that verified my great-great grandpa’s parentage: John Clark had been born to William and Mary Clark of Highland, Wisconsin.

But who were William and Mary Clark, and where did they come from?

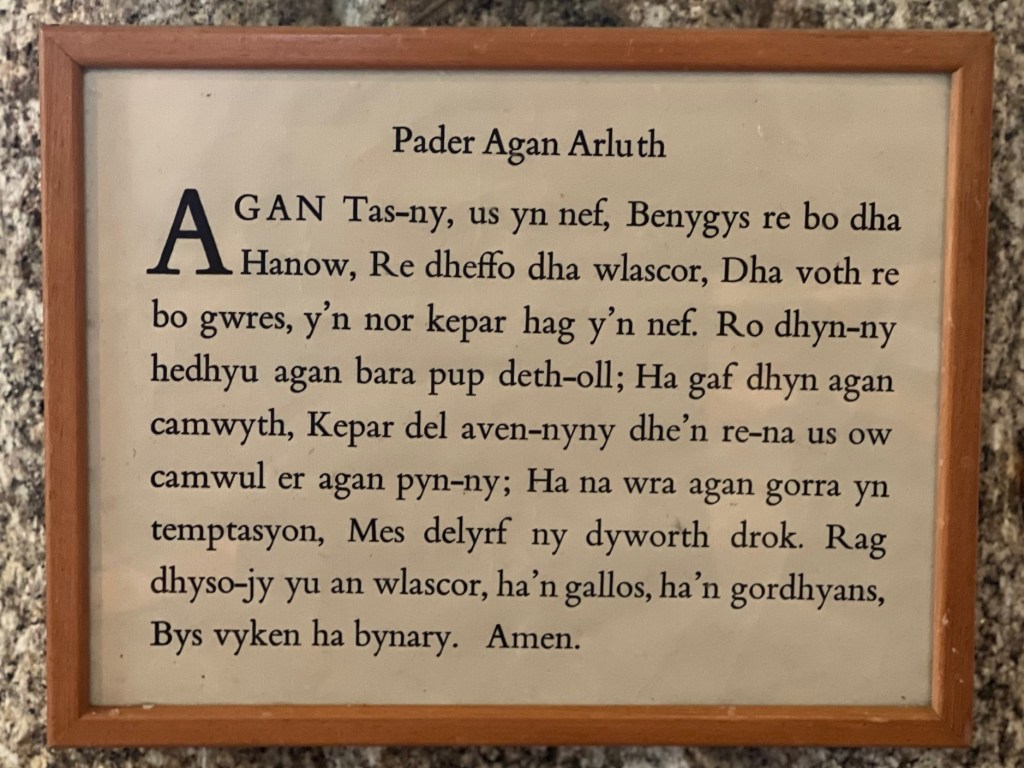

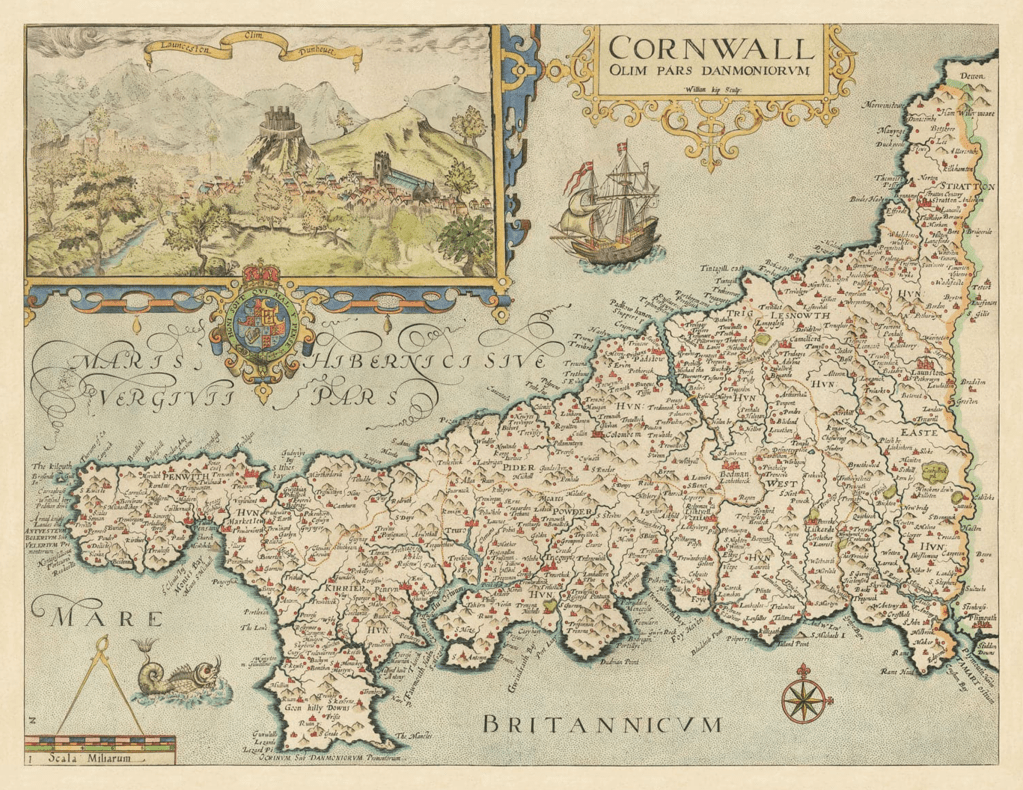

Over the years I’ve had little luck in solving the mystery of William Clark (sometimes spelled Clarke). Every source document I’ve found lists his origins simply as “England.” There were dozens of William Clarks born in England around the year of his birth (1827) and several who immigrated to the U.S. in the year he was believed to have come over (1852). But the story of his wife Mary has become clearer with time and additional research. The notes below are a summary of what we know about the family of my great-great-great grandma, Mary Clark (maiden name Cock, later Cox).

Direct ancestors of my paternal grandmother’s mother, Ruth Clark (Confused where this fits in? See this page.) * * *

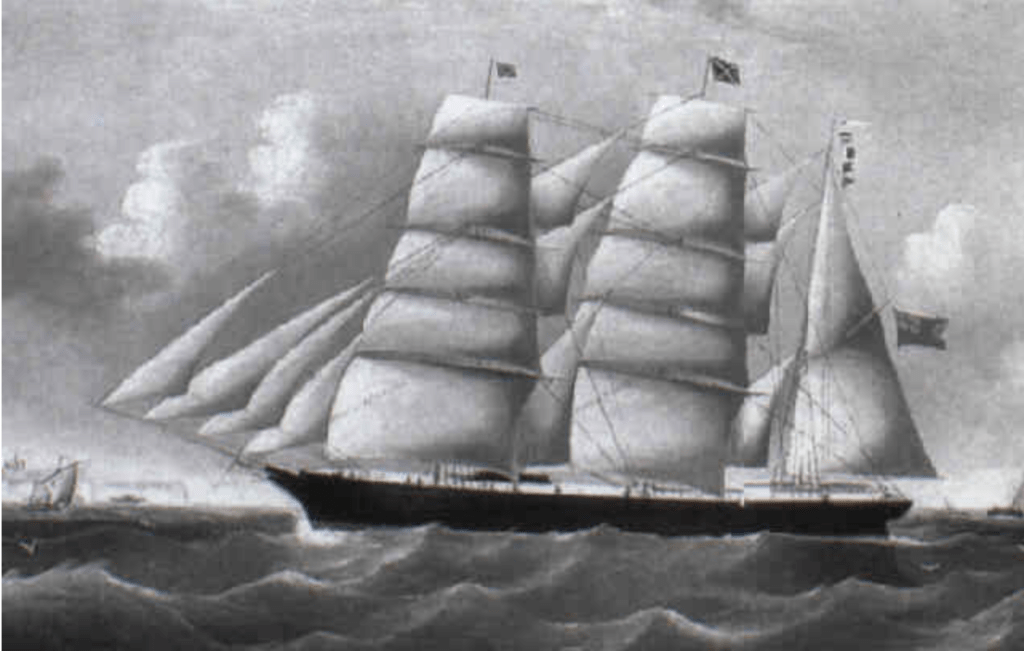

“The Barque Cornwall signalling for a pilot off Dover”, oil painting by Richard B. Spencer (1812-1887) Mary Cock was still a young girl when she and her siblings, accompanied by female relatives, arrived from Penzance on the Barque Cornwall into New York Harbor. The day was August 23rd, 1849. Mary’s father, Charles Cock (born 1815), had been a copper miner in Cornwall, England. Like many of his Cornish compatriots, Charles was no doubt enticed by the prospects of mining in southwestern Wisconsin. Indeed, there had been a steady flow of Cornish miners into the area since the 1830s. Charles, his brother Francis, and his brother-in-law Oliver Honeychurch appear in Wisconsin’s 1850 Census but they are not listed on the 1849 ship manifest of the Barque Cornwall, so my best guess is that these three men arrived earlier to establish themselves in Wisconsin.

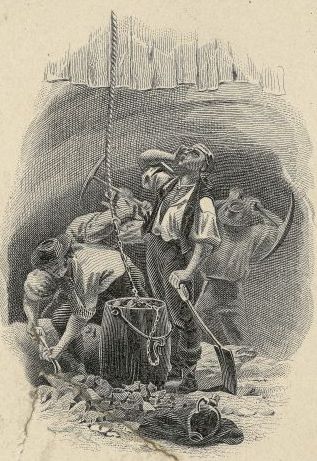

Illustration of miners, unknown artist and source, downloaded from the Wisconsin Historical Society website (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM111974) Eight years earlier, the 1841 Census in England lists the family as living in Lanyon within the parish of Gwinear – just to the southeast of St. Ives. Charles (age 25) and wife Alice (27) had three children at this time: William (3), Alice (2), and my great-great-great grandma, Mary (1). Also listed is Elizabeth Mitchell (67), Alice’s mother. Other family historians have researched branches of the Cock and Mitchell families back several generations. I cannot verify their research, but it would appear that these families have deep Cornish roots. (In this post, I write a little about what their life in Cornwall may have been like.)

1814 map of Cornwall, downloaded from https://www.cornwalleng.com/historical-maps.html Mary’s post-immigration life is somewhat easier to trace. We know she wed William Clark in Ridgeway, Wisconsin in 1854, when she would have been only 14 or 15. In the 1850s and at least through the early 1860s, the Clarks lived in the vicinity of Ridgeway, and William worked in a mill. But by 1870 the family was living in the town of Highland, Wisconsin, and they ran a small farm. They raised six children in those years (approximate birth years in parentheses): Mary Ann (1857), Charles W. (1860), Alice (1861), my great-great grandpa John (1864), Nellie (1868), and Emma (1870). In her later years, after William had passed away, Mary lived with one and then another of her younger daughters until her death in 1919. Her grave can be found just off Highway 14 in Mazomanie Cemetery.

Grave of Mary Clark, Mazomanie Cemetery What became of Mary’s parents, Charles and Alice Cock, has yet to be revealed. They seem to vanish from the historical record. For starters, it’s unclear whether Mary’s mother is listed on the Barque Cornwall manifest of 1849. There are two young women with the last name Cock who accompanied the children over – a Jane and a Betsey Cock. The ages and names don’t match, but perhaps one of these women is the same as “Alice” who appears in England’s 1841 Census? Adding to the confusion, the children’s mother is also absent from the 1850 Census in Wisconsin. That record shows the children living with their father Charles and a large number of family members on their father’s side: their father’s brother Francis, his sister Hannah Maria, Hannah Maria’s husband Oliver Honeychurch, and their Honeychurch cousins. (Hannah Maria and her daughters also appear on the Barque Cornwall manifest.)

Mary’s father Charles shows up on both the 1850 and 1860 censuses, although his surname changes from Cock to Cox. By 1870, however, he too disappears from the historical record; I have yet to locate a death certificate or a grave.

Of course, this is the nature of mining for genealogical ore. You can spend a lot of time digging in one direction and come up with nothing. Then suddenly a new nugget of knowledge is unearthed – often in the unlikeliest of places – which provides clues to further discoveries. The Clarks’ story remains buried, but I hold out hope that one day I’ll find the mother lode.

Peter Lanyon (1918-1964), “Lost Mine” (1959), oil on canvas, displayed at the Tate St. Ives in Cornwall. The description next to the painting explains: “The mine shaft is painted in black and seems to signify death, the blues are the sea and sky, and the red signals both life and danger.” -

Gene Smith on the eve of World War II

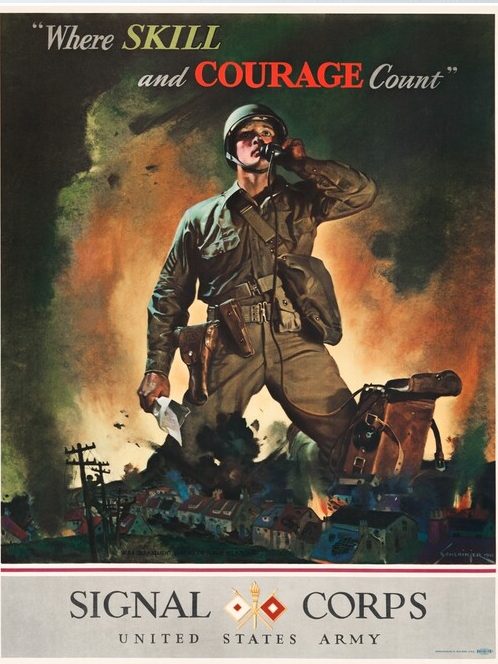

Think of World War II and, if you’re like me, you probably imagine it a bit like a movie. And thanks to compelling movies like Saving Private Ryan and Dunkirk, we might picture men doing heroic deeds in the face of uncertain odds. Don’t get me wrong – this kind of heroism did occur and ought to be remembered in film. But consider another side of the War for a moment. Consider what it took to mobilize millions of Allied troops, send them into battle, and supply them with all the necessities of both war and daily living. Consider what it took to coordinate all their movements and communications in a world before the computer chip, satellites, or the internet.

The logistics behind the War were monumental. At its peak in 1944, the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps included over 350,000 servicemen and women.[1] My grandpa Eugene Smith was one of those servicemen. Starting in the autumn of 1943, he served in Company C of the 3110th Signal Service Battalion. In the spring of 1945, he was transferred to Company A, First Platoon of the 3160th Signal Service Battalion.

A couple of years ago I came across a blog post about a Signal Corps solider named Felix Cizewski, and my heart skipped a beat: my grandpa and Felix had served together in Company C of the 3110th. The two men undoubtedly knew each other, and their experiences would have been similar. The blog’s author Leonard Cizewski was Felix’s son, and he has painstakingly researched his father’s wartime record. We’re indebted to Leonard for his work on this subject. Like most men of their generation, Leonard’s father Felix and my grandpa Gene didn’t talk much about their time in the War. What we know about their experiences we’ve had to piece together from fragments: Army records, the odd photo here or there, and letters home.

My grandpa Gene and his new bride Phyllis tried to write each other a letter every day during the War. They didn’t always succeed, but they came close. And because both my grandma Phyllis and her mother-in-law Vina were fastidious about keeping Gene’s letters, many of them survive today. I’ve mined those letters, Leonard’s blog, and a few other sources to piece together a rough history of my grandpa’s time in the Army. My goal is to write this history in three parts: (1) Gene’s pre-deployment in Missouri and New Jersey (spring 1943 – early 1944); (2) his service in England during the spring and early summer of 1944; and (3) his service in France after D-Day to the end of the War (summer 1944 – late 1945).

But before I get into that history, I want to sketch for you a young Gene Smith. This was a Gene Smith I never met but who I can picture to an extent – because even as my grandpa got older and his health started to fail, you would get glimpses of the lively, driven young man he used to be.

Gene was Vina and Frank Smith’s first child, born in 1921 when the couple lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Frank worked as a streetcar conductor. The Smiths left the city while Gene was still little. First, they moved to Cambridge, Wisconsin, which was close to both Frank and Vina’s families, and Frank worked for Standard Oil, delivering gasoline to local farms. Then, for several years, the family moved from place to place in the area, renting farms and doing their best to make a living off them. Frank and Vina eventually found steady farm work as suppliers to the Fort Atkinson Canning Company, but they never had much money.

A young Gene Smith at the Hillside School, located between Edgerton and Cambridge, Wisconsin Gene was a bright kid, but he didn’t get the chance to stay in any one school for long before he had to move on to the next. Perpetually the “new kid”, he learned to adapt to unfamiliar environments and to stick up for himself and his younger sisters, Shirley and Ruthie. While he tolerated farm work, it was never his passion. Gene was a bit of a dreamer by nature, but his modest upbringing made him pragmatic and resourceful. He enjoyed drawing and word games, but he also loved to tinker with machines and figure out how they worked.

From left: Vina, Shirley, Frank, and Gene with Ruthie below (mid-1930s, in front of their farm just south of Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin) When it came time for high school, Frank didn’t see much point in Gene attending. But here Vina put her foot down: both she and Frank had been denied a high school education and she argued that Gene should have the opportunity. So, Gene went to Fort Atkinson High, and it would appear that going to school did open Gene’s eyes to other possibilities.

Gene Smith’s high school graduation photo After graduating in 1938, Gene moved out and supported himself through a series of odd jobs. Eventually, he managed to land himself an entry-level position in a field he was truly interested in — electronics. The job was with the Western Electric Company in Milwaukee, a subsidiary of AT&T. It must have been an exciting time in Gene’s life; he was living on his own, he had a little money in his pocket for once, and Western Electric’s products were at the forefront of that era’s technology in communications.

Adding to the excitement, Gene had started going out to dancehalls to meet girls. In the summer of 1939, at a dance hall in Lake Mills, one girl in particular caught his eye. A farm girl from Cambridge, Phyllis Reiner laughed easily, danced with abandon, and asked a million questions. She was young – only 16 – but she seemed as taken with Gene as he was with her. They started writing letters to each other and met up for dates on the weekends when Gene could get away from work.

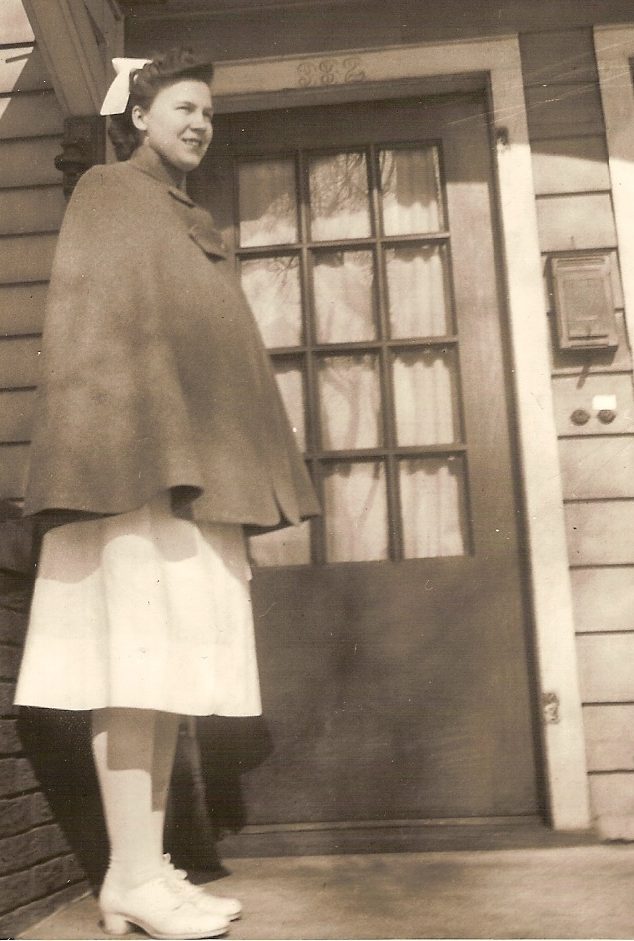

Phyllis and Gene when they were dating Like Gene, Phyllis had ambitions for a life beyond the farm. She dreamed of becoming a nurse, and after graduating from Cambridge High in 1941 she began a nurses training program at St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison. The young couple continued their courtship through letters and brief visits when they could arrange them. But Gene and Phyl’s carefree lives – like the lives of most young people at that time in America – were about to change dramatically. As Hitler sent his forces across great swathes of Europe and as he aligned himself with authoritarian regimes in Japan and Italy, war seemed ever more likely. Britain and other allies implored the U.S. to declare war. In December of that year, Japan’s attack on Hawaii and the Philippines (then U.S. territories) proved to be the tipping point. With America entering the War, the fate of young men like Gene was suddenly up in the air.

Phyllis (at right) at St. Mary’s (circa 1942) What a tumultuous moment this was for all American families, as the country, barely recovered from the Great Depression, geared up for war on two fronts. For Gene and Phyl this moment must have also been colored by their young love and worries about how the war might change things. Complicating matters, a case of tuberculosis forced Phyllis to take a leave of absence from nursing school. For several months she was isolated, confined to bed rest at her family’s farm while she recovered.

Military recruiters, meanwhile, wasted no time in appealing to young men across the country to do their duty and join the armed forces. Given Gene’s interests in electrical engineering and communications, the recruiters in Milwaukee told Gene he could be an asset to the Signal Corps. They promised he would receive additional training in these fields, which could boost his career when the war was over. That proved compelling to Gene, and he enlisted on August 12th, 1942.[2] True to their word, the Army sent Gene to Army radio school for three months in Janesville, and then to a radio school in Milwaukee. He graduated there on March 1st, 1943, and went home for a couple of weeks to see Phyllis and his family.

On one of his visits with Phyllis during during this time, he popped the question and presented her with an engagement ring. The two of them didn’t know when or how they would get married, but they were certain they wanted to make it happen one way or another.

Gene reported to the induction center at Fort Sheridan, just north of Chicago, to begin active duty on March 16th.

He had become Private Smith.

To continue this story sequentially, you can read about Gene’s pre-deployment Signal Corps training in this post.

1942 Signal Corps recruiting poster

[1] See p. 280 in Rebecca Robbins Raines’ (1996) Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army.

[2] This propaganda film produced by RCA, “Radio at War”, gives some insight into what enticed Gene to the Signal Corps and what he might have expected Army life to be like: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WUx_hqwHM1I.

-

A mystery solved – the Wackrows of Müggenburg

Hartmut has saved the day — again! If you’ve read my prior post about the Schmidt family of Müggenburg, you’ll know that my knowledge about this branch of my family (my mother’s father’s father’s side) is wholly thanks to the efforts of one local historian, Mr. Hartmut Wegner of Mönkebude.

Hartmut and Helga Wegner When Hartmut read that post about how I’d traveled to Müggenburg and met a man named Bernd Wackrow (who I imagined could be a distant cousin), he was inspired to do even more research on my behalf.

The depth of Hartmut’s generosity and kindness is hard to fathom. He actually drove down to Müggenburg himself, found and spoke to Bernd, and then went back to his computer for several days of desk research. How many hours he spent scrolling through scans of old church records, I’ll never know. But in the end, Hartmut cracked the mystery and, in the process, revealed to me a family tree much larger and more complicated than I’d previously known.

Wackrow family tree The photo above is hard to see, but it’s a print out of a new family tree that Hartmut made, spread across five pages on my floor. This new tree shows that Bernd and I are fifth cousins: I am the descendant of Wilhelmine Friederike Wackrow (my great-great-great grandma, mother of Wilhelm Schmidt) and Bernd is the descendant of her sister Maria. Before she married in 1853, Maria gave birth to a son in 1845 named August who took his mother’s maiden name. That was Bernd’s great-great grandpa. Had that name not been passed down, I wouldn’t have thought to knock on Bernd’s door 177 years later.

And that’s the contingency of history for you. One small change, one small decision can have a ripple effect for centuries. My ancestors decided to seek work elsewhere — across the Atlantic in North America. Had they not, my ancestors would have worn the same military uniforms as Bernd’s ancestors. We all like to think of ourselves as individuals, freely choosing the path our lives take. But none of us are immune to the sweeping course of history. We all get caught up in its currents.

From Bernd’s family album

From my family album I am writing this post today with a very full heart. I am exhausted from my travels (on top of my jet lag, I’m recovering from COVID). But I am feeling extremely grateful to Hartmut Wegner for unlocking several mysteries about my family from Pomerania. Without preservationists like Mr. Wegner, our world would be missing the depth and perspective that history affords us. We are in your debt, Hartmut!

Hartmut holding the key to history -

Missed connections

Hello from Iceland! This stop was not on my itinerary, but I missed my connecting flight in Reykjavik so I’ve spent the night here.

This got me thinking about the less-than-obvious connections between the two countries I’ve just visited — Norway and Germany.

Physically, Norway and Germany are separated only by a couple of modest-sized bodies of water: Skagerrak and Kattegat. Skagerrak is the strait just south of the Oslofjord between Norway and Denmark. Kattegat is the strait just south of this, between Denmark and Sweden. Collectively, these two straits and the Danish islands separate the North Sea from the Baltic (or what people in most Germanic-language countries call the East Sea).

Map of Skagerrak and Kattegat, shamelessly stolen from Wikipedia Last Tuesday I had the pleasure of journeying by boat between Oslo and Kiel, which took me through this narrow passage (in point of fact, “Kattegat” derives from the Dutch for “cat’s gate” — a gate so narrow only a cat could get through).

Bad hair day

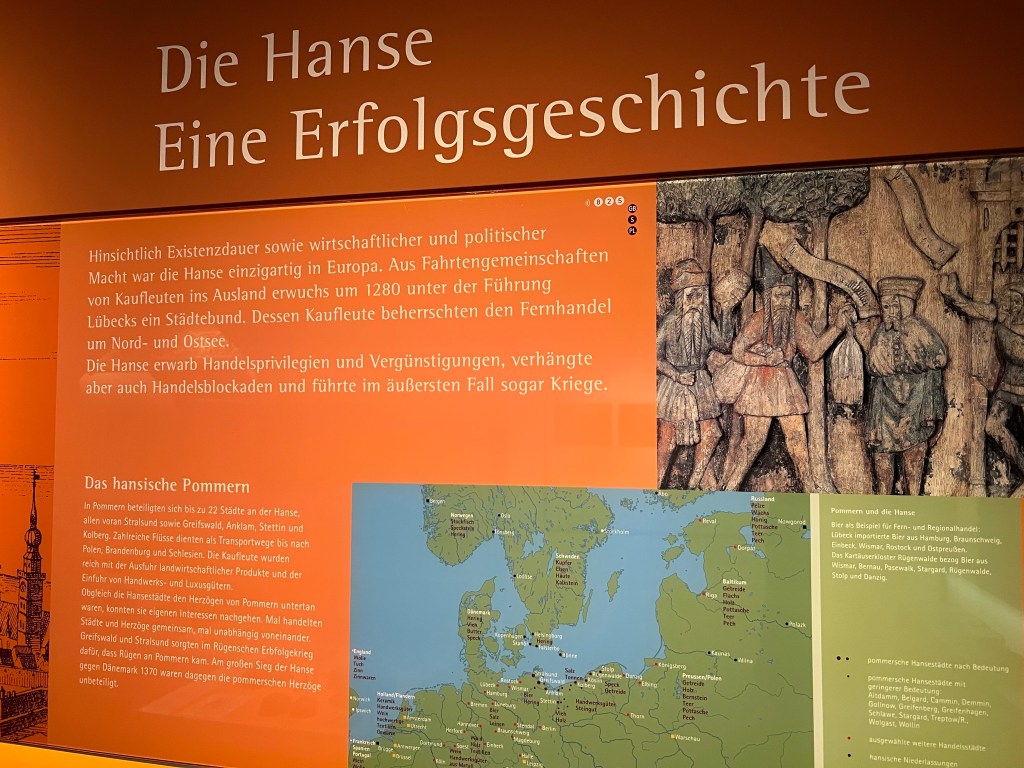

View of the Oslofjord from the boat Which brings me to that first not-so-obvious connection between Germany and Norway: the historically important trade in stockfish — i.e., freeze dried fish, typically cod. Skagerrak and Kattegat were the shipping lanes used by the Hanseatic merchants who dominated these seas for centuries. It’s easy to forget about the Hanseatic League, but this confederation of member cities and ports operated a little like its own country from the 13th to the 15th centuries. Some even say it was a precursor to the European Union.

At its center was Lübeck, where the Hanseatic merchants occasionally met to make joint decisions. I took a stroll through Lübeck on Wednesday — a city simply dripping with history.

The Holstentor (Holstein Gate) in Lübeck

Scenes from Lübeck And I visited two other important Hansa cities — Rostock and Greifswald, each with a sure sense of its place in the world. Rostock in particular was decimated by the War and was rebuilt as a showpiece of Germany history.

Scenes from Rostock

Scenes from Greifswald At this point you must be thinking, “Very pretty pictures, Jesse, but what does this have to do with the trade in stockfish?” Ah… that’s where Norway comes in. One of the most important Hanseatic outposts was in Bergen (see my post from a couple of weeks ago). The Hanseatic merchants’ kontor in Bergen was where Europe got its stockfish. And stockfish was big business back in the days before refrigeration.

Dorking out on Hanseatic history at the Pomeranian State Museum (Pommersches Landesmuseum) in Greifswald, Germany

Can you imagine what Bergen smelled like in 1422?

In Cod We Trust. A map of Hansa trading ports from the Hanseatic Museum in Bergen.

Bet you didn’t think you’d be reading about stockfish today!

This is a photo of the exterior of a Hansa Kontor in Bergen.One of the most obvious connections between Norway and Germany is the fact that between April 1940 and May 1945, Norway was occupied by Germany under the Third Reich. (And as I’ve mentioned in a prior post, there’s a fascinating outdoor art exhibit at Roseslottet in Oslo that explores the occupation years.)

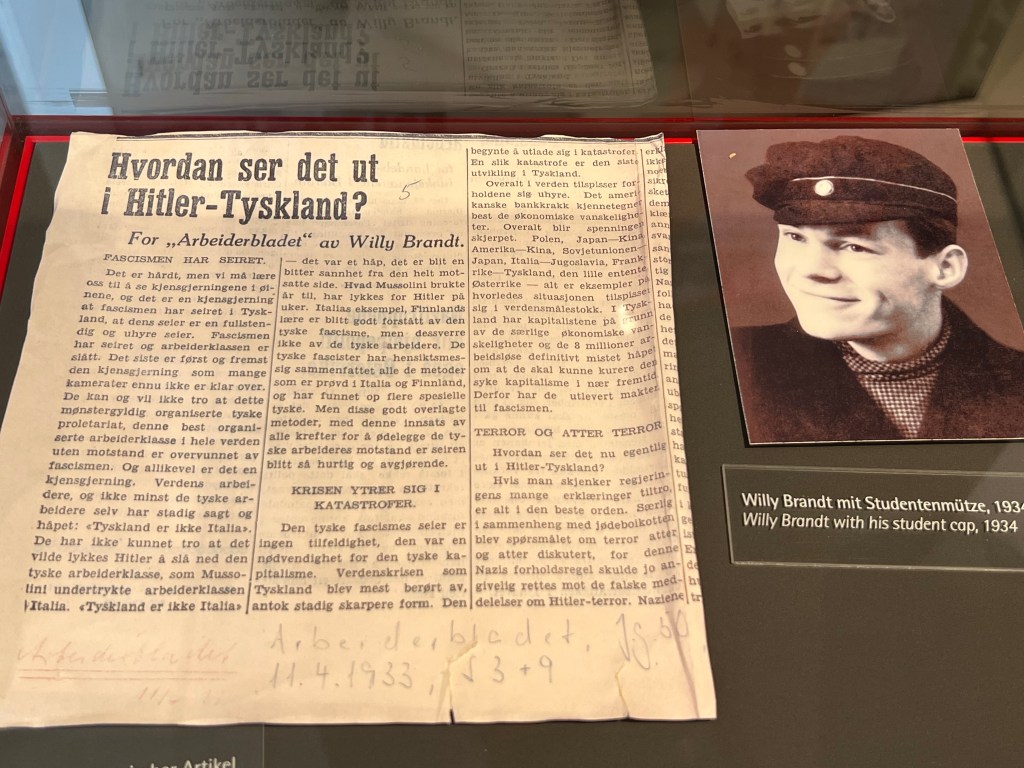

But one facet of those War years that is sometimes overlooked is that one of the key leaders of the German resistance against the Nazis exiled himself in Norway (and later Sweden after Norway fell to Germany). That leader was Herbert Frahm. Never heard of him? Of course you haven’t. The world knows him by the name he gave himself while working as a student journalist in Norway — Willy Brandt.

Brandt in exile in Norway, ca. 1935 (photo of a display at the Willy Brandt house museum in Lübeck) After the War, Brandt went on to become one of Germany’s most famous politicians and leaders. He led West Germany’s Social Democratic Party from 1964 to 1987 and served as the country’s chancellor from 1969 to 1974.

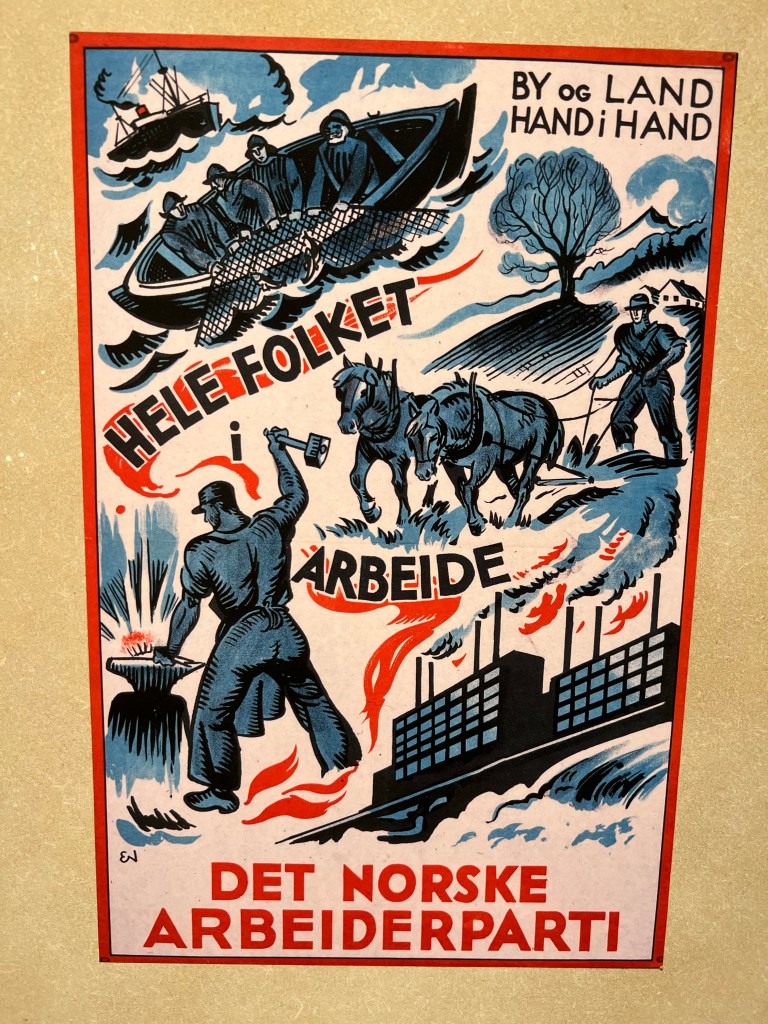

Brandt came to Norway in 1933 to escape persecution from the Nazis, and he quickly became involved with leftist politics and journalism in Norway. Within weeks Brandt was publishing articles in Norwegian about Hitler’s rise to power and urging Norwegians to resist fascism. He also became involved in helping support the nascent workers movement in Norway.

Norwegian workers party poster from the Willy Brandt home in Lübeck

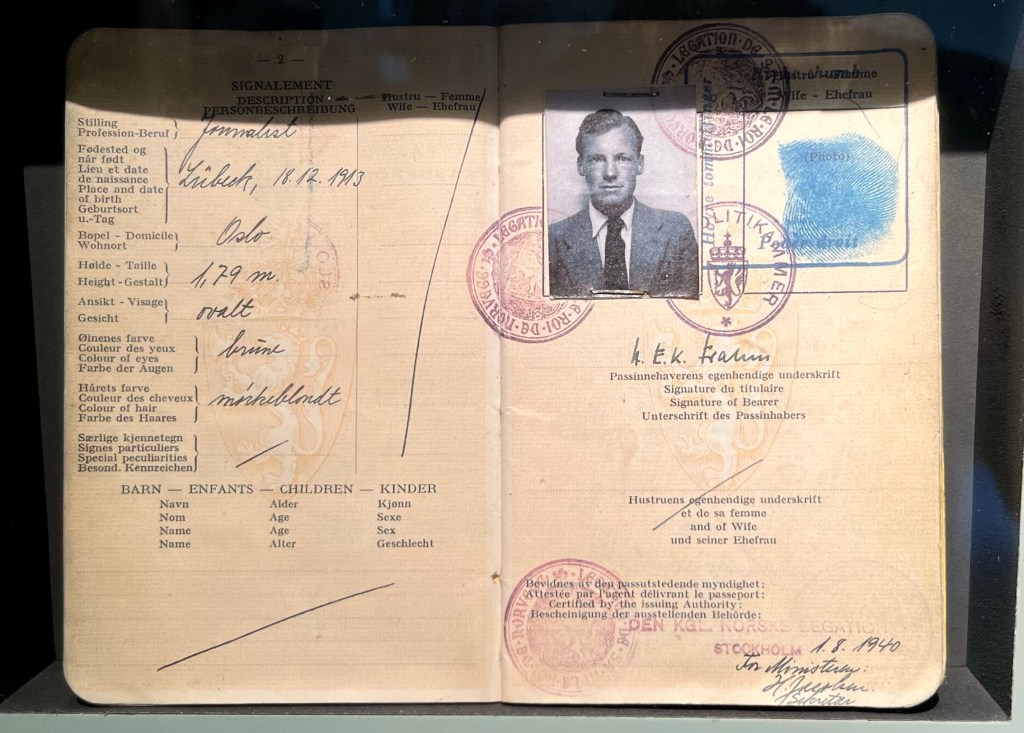

Brandt’s journalism in Norway on life under Hitler in Germany Brandt honed his political philosophy in Norway, becoming less revolutionary and more pragmatic. But he never gave up on the idea of a free and democratic Germany. In reaction to his journalism, the Nazi authorities stripped him of his citizenship in 1938. When Germany invaded Norway in 1940, Brandt fled to Sweden and was granted a Norwegian passport there.

Brandt’s Norwegian passport (on display at the Brandt home in Lübeck) After the War, Brandt helped forge a new Germany. While he continued to be an outspoken anti-fascist, Brandt used his political power to achieve reconciliation between West Germany and the Eastern Bloc. For these efforts, Brandt was awarded the Nobel Peace Price in 1971.

Willy Brandt home in Lübeck

A piece of the Berlin Wall on display at the Willy Brandt home in Lübeck

Willy Brandt Street (Berlin)

Vebjørn Sand’s portrait of Willy Brandt when he was a young Herbert Frahm; Rose Castle (Roseslottet) in Oslo Yesterday as I flew out of Berlin’s Willy Brandt Airport, I asked myself, “Would Germany be the same today if Brandt had not been influenced by Norwegian political thought in the 1930s? Would Norway be the same today if Brandt had not published his ‘insider accounts’ of German fascism in Norway’s newspapers?” Both countries were enriched by this connection.

And speaking of connections, I must go now and make my next one. Because as fascinating as all of these travels have been, the place I most want to be right now is home.

-

In search of the Lehmanns

I drove out into the German countryside today to get a sense of where my grandma’s grandma came from.

Standing at back: Barbara Jean Kaufman, Ruth Clark Kaufman, and Edward Carl Kaufman; standing in front: Edward Clyde Kaufman and Jack Kaufman; seated: Louise Lehmann Kaufman

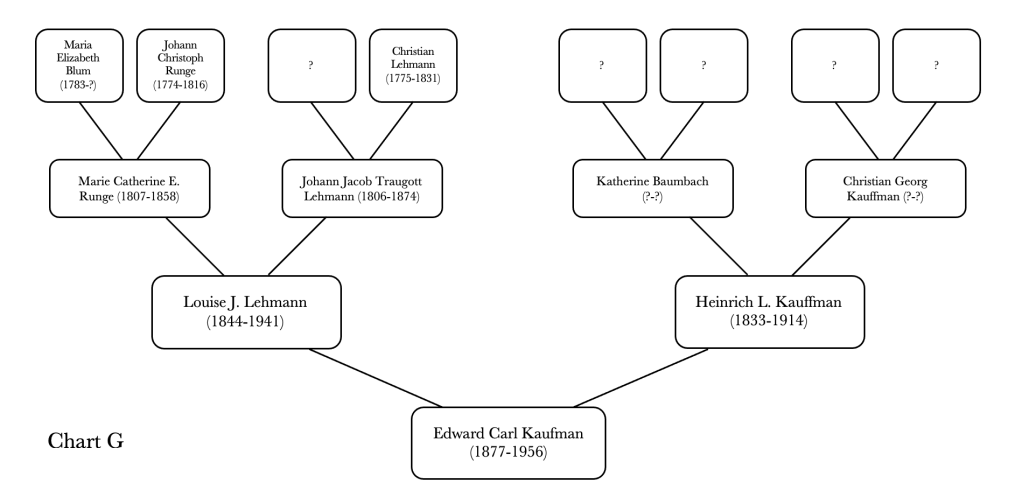

Direct ancestors of my great-grandpa Edward Carl Kaufman The grandma in question is Louise Lehmann Kaufman, the mother of my paternal grandma’s father, Edward Carl Kaufman. My great-grandpa Ed Kaufman is the man on the right in the photo above. His mother Louise is the old woman seated below. And her granddaughter, Barbara Jean Kaufman (standing at left), is my grandma, who is nearly 96 years old now and still going strong.

Grandpa Ed was born on August 9, 1877 in Edgerton, Wisconsin. Both of his parents — Louise Lehmann Kaufman (1844-1941) and Heinrich (“Henry”) Kaufman (1833-1914) — immigrated from Germany. But whereas Grandpa Heinrich arrived as an adult in the 1860s, Grandma Louise came as a girl with her parents in the 1850s.

Grandma Louise’s parents (i.e., my great-grandpa Ed Kaufman’s maternal grandparents) were Maria “Catherine” Runge and Johann “Jacob” Traugott Lehmann, immigrants to Wisconsin from the province of Brandenburg within the Kingdom of Prussia. At the time Catherine and Jacob married in 1831, Prussia was the most powerful member of an alliance of 39 German kingdoms and duchies called the German Confederation, which predated the German Empire established in 1871. In the mid-19th century, the province of Brandenburg straddled the Oder River, which now separates Germany from Poland.

My best guess is that Catherine Runge and Jacob Lehmann were born in farming towns a few miles north of Frankurt an der Oder (not to be confused with the much larger city of Frankfurt am Main in the west). I am not entirely certain of their towns of origin, but it appears they married in Groß Neuendorf on January 2, 1831.

The current church in Groß Neuendorf, which dates to 1850, replaced a church here from 1703. That earlier church may be where our ancestors married.

(And no, I have no idea why there are a bunch of children’s toys on the front steps. It looks like a family may be living in this church.)

The road to Groß Neuendorf, like many German country towns, is lined with oaks.

Looking across the Oder River from Groß Neuendorf to Poland

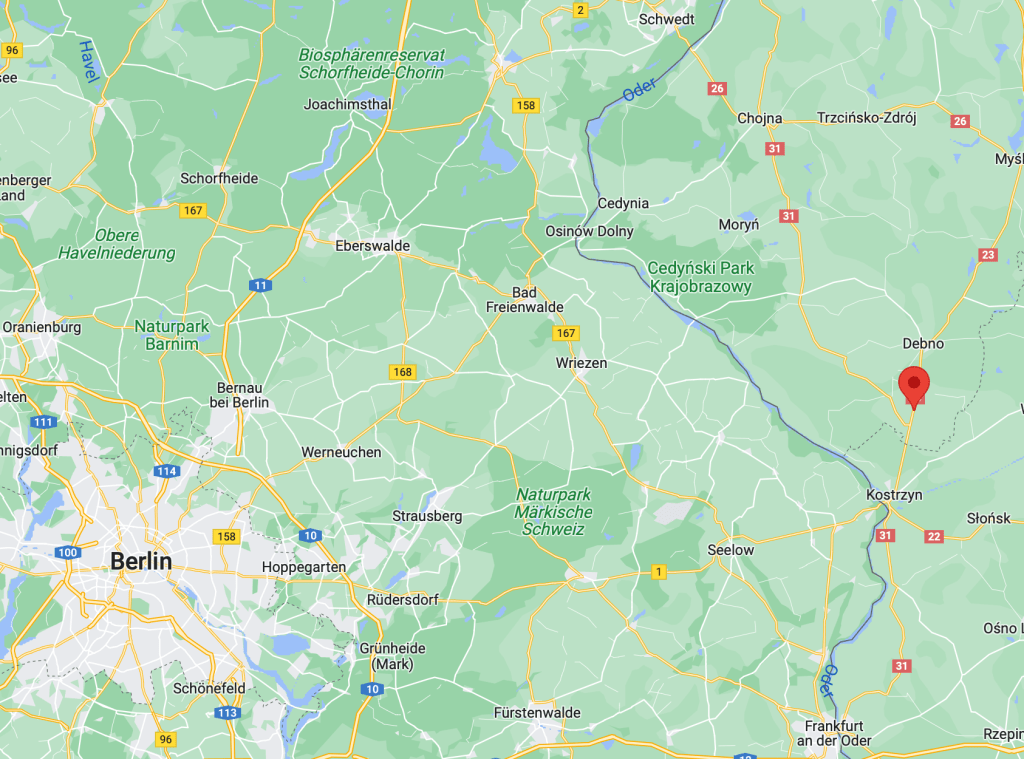

Here’s a sight our ancestors might recognize — the tower from the church in neighboring Letschin, which now stands on its own. It was originally constructed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel in 1818-1820. In the years after Catherine and Jacob married, they leased a farm in a small village once called Zicher in the section of Brandenburg on the east side of the Oder called Neumark. The village later became known as Cychry, Poland after the Soviet army gained control of the area in 1945 and has since been annexed into the administrative region of Dębno. I took a drive over there to check out the area.

Location of Zicher, Neumark (now Cychry, Poland)

Does the tower look familiar? This is the church just south of Cychry in Sarbinowie, Poland. It was built in 1832 and yes, the tower was also designed by Karl Schinkel. Today the church is Roman Catholic (Kościół Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny w Sarbinowie).

There are still many examples of German-style architecture on the east side of the Oder River.

Farmlands in the former Neumark, now Poland Catherine and Jacob Lehmann had seven children in Zicher before emigrating: August (1833), Johann (1836), Carl Frederick (1839), Augusta (1842), our ancestor Louise (1844), Wilhelmine (1846), and Caroline (1849).

Grandma Louise Lehmann Kaufman standing with her sisters seated (left to right): Wilhelmina (Mina) Lehmann Goede, Augusta Lehmann Ruosch, Caroline Lehmann Gessert-Schachtschneider In 1856 the Lehmanns journeyed to Hamburg and boarded the Rhein for New York. The voyage took more than six weeks, and we can imagine how stressful it must have been for the family of nine.[1] My great-great grandma, Louise, was 11 at the time. The family made their way to Watertown, Wisconsin (Jefferson County), and no doubt quickly tapped into the thriving Germany community that had been established there since the late 1840s.

After visiting the lands on both sides of the Oder, it was clear to me that settling in Wisconsin must have felt somewhat like home to the Lehmanns. With its rolling farmlands, these regions in Germany and Poland have much the same feel as Southern Wisconsin.

Sunflowers growing in the Märkisch-Oderland *** Update and correction based on the information from Teddie Anderson Hill (see her comment below) ***

The exact village the Lehmanns lived in was Neu Zicher, not Zicher, which corresponds to Suchlica, Poland today. I drove through Suchica, and in fact the photo above of “Farmlands in the Neumark” (with squash and wheat) was taken in Suchlica.

Teddie is correct in saying that there is no church in Suchlica. (There’s not much of anything in this tiny village!) There’s a church that dates to the times of our ancestors just south of Suchlica in Sarbinowie (photo is above). And there’s also a Roman Catholic church in Cychry, which was Protestant before the 1950s. The building dates back to the 13th century and the tower dates to 1768. It’s likely that either this church or the one in Sarbinowie was the home church for the Lehmanns before they emigrated.

Church of Saint Stanislaus in Cychry (Kościół Rzymskokatolicki p.w. Św Stanisława)

Just outside of Suchlica (formerly Neu Zicher) in Poland

[1] Much of what we know about the Lehmanns is thanks to the genealogical research of Teddie Lynn Anderson Hill and her mother Darlene “Donna” (Lehmann) Eichorst, descendants of Grandma Louise’s brother John T. Lehmann.

-

The Hahn and Sahr families of Woltersdorf

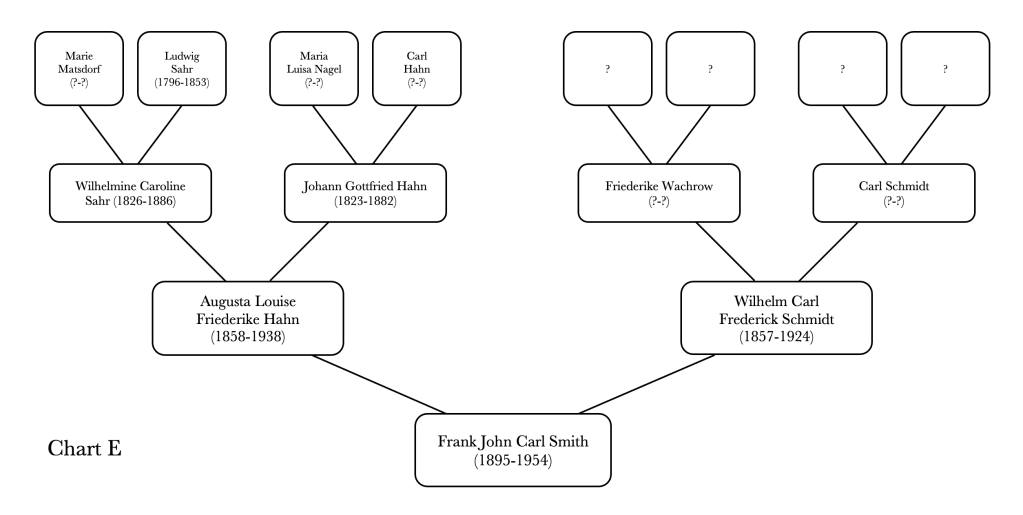

Today I visited Woltersdorf, Wartin and Blumberg — small villages that were home to my great-grandpa Frank Smith’s mother’s families — the Hahns and Sahrs. (For information about Grandpa Frank’s father’s family, see this post.)

The farmland just outside Woltersdorf

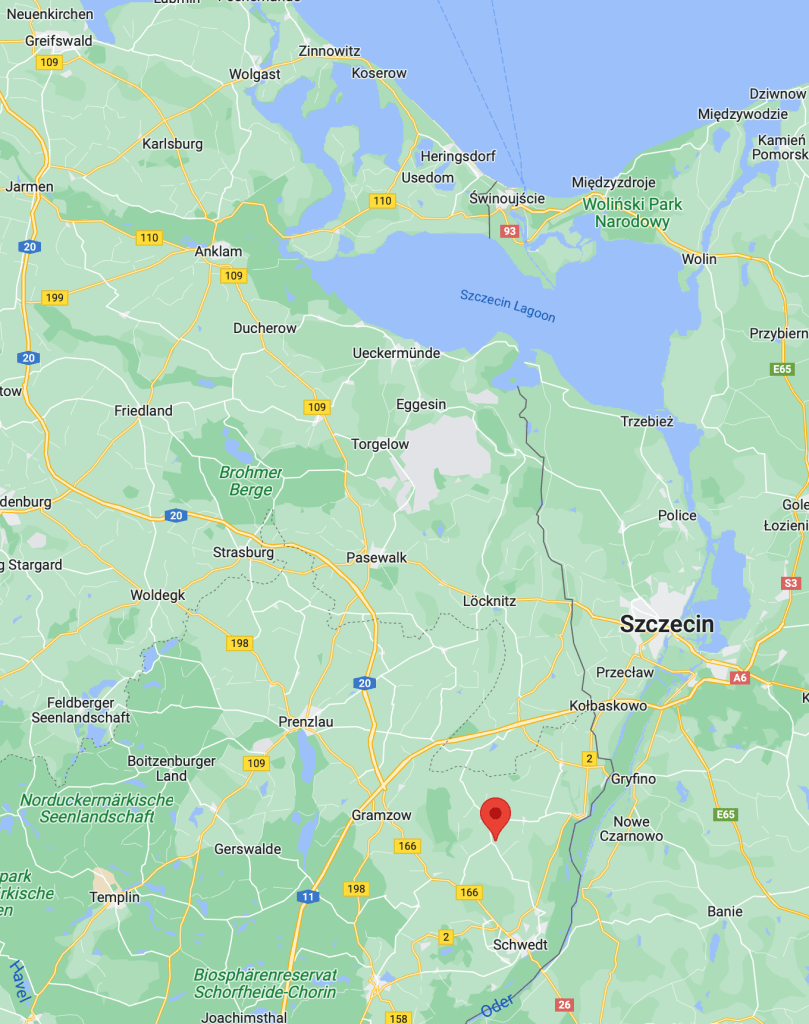

Location of Woltersdorf (formerly in Kreis Randow of Pomerania, now in Brandenburg) The region is home to sprawling farm fields — mostly wheat and hay, but occasionally corn and sunflowers. In some places giant wind turbines dominate the landscape. In each of the villages, I visited the local church, walked the graveyards, and tried to find names that I recognized. Unfortunately, I came up against the family historian’s biggest foe — time.

Woltersdorf Church is now a rundown shadow of its former self.

Gravestones have been moved to the side of the churchyard (Woltersdorf Church) and many of the names are illegible.

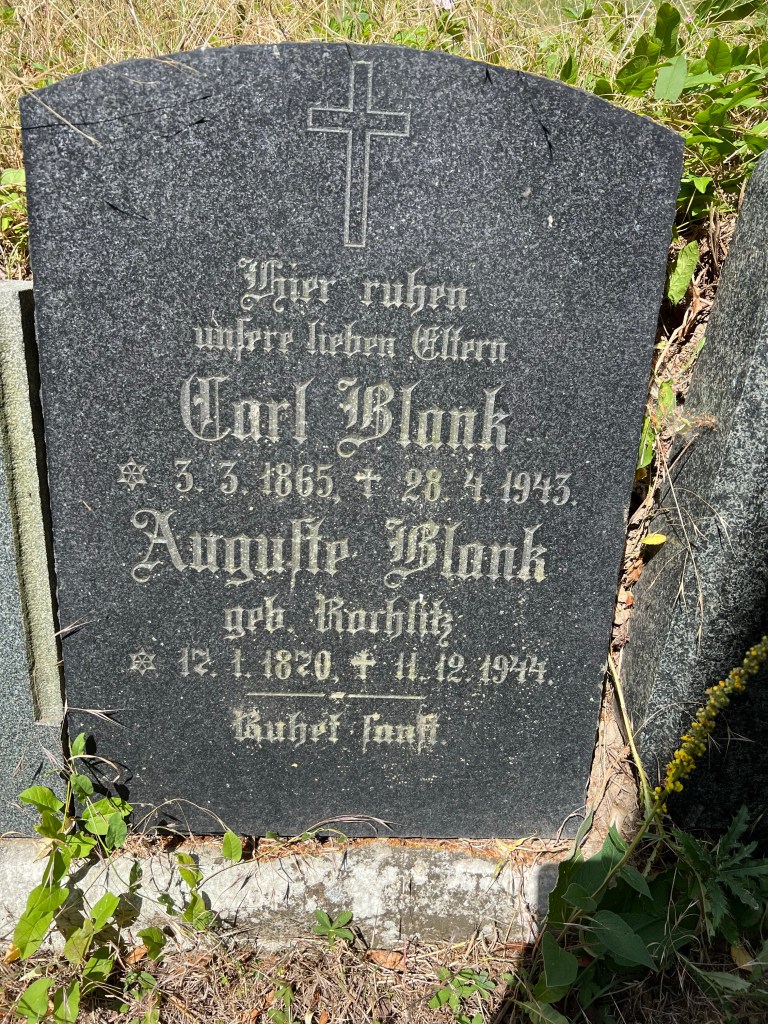

One name I recognized at Woltersdorf— Blank. My great-great grandma Augusta Hahn Schmidt’s brother Wilhelm C. Hahn married Caroline Blank.

A family plot at Woltersdorf that is completely overgrown. Is this my family plot? Is it yours? Who knows?

Churchyard at Wartin — The notice on this grave reads: “Acute risk of accident. This grave marker is no longer stable and must be professionally repaired immediately.” My assumption is that when no action is taken within a given time (after the two “green” warnings and the “red” warning), the grave marker is removed to the side of the churchyard.

A peek through the windows at the Wartin Church. Like Woltersdorf, Wartin was a 13th century Gothic fieldstone church, but it suffered great damage and had to be rebuilt in the late 1600s.

Wartin Church exterior. The marker in front commemorates WWII dead from the area.

A peek through the windows at Blumberg Church — another 13th century fieldstone church used by our family.

Blumberg Church exterior My great-grandpa Frank’s mother Augusta was born as Auguste Luise Friederike Hahn on September 14, 1858. Her birthplace of Woltersdorf was part of what was then Kreis Randow, the county southwest of Stettin in Pomerania.[1] Today the area is part of the town of Casekow, which is only a few miles from the Polish border and just within the boundaries of the modern German state of Brandenburg. Augusta’s parents were Wilhelmine Caroline Sahr and Johann Gottfried Hahn.

Augusta’s mother Wilhelmine Caroline Sahr was born on February 28, 1826 in nearby Wartin to Marie Matsdorf and Ludwig Sahr. Augusta’s father Johann Gottfried Hahn was born in Woltersdorf on September 26, 1823, and his parents were Maria Luise Nagel and Carl Hahn – a day laborer (Tagearbeiter).[2]

Direct ancestors of my great-grandpa Frank Smith Augusta was one of at least eight children born to Wilhelmine Caroline and Johann Gottfried Hahn after they had married in Woltersdorf on September 6, 1849.[3] From church records, we have been able to identify the children as follows: Carl Ludwig Wilhelm (1849), Johann Wilhelm (1851), Johanne Caroline (1852), Wilhelm Martin Friedrich (1854), August Carl Wilhelm (1856), our ancestor Augusta (1858), Wilhelm Carl (1860) and August Wilhelm Carl (1862).

Four of the Hahn siblings – the eldest child Carl L.W., our ancestor Augusta, Wihelm C., and the youngest child August W.C. – immigrated to Wisconsin in the early 1880s, along with their widowed mother Wilhelmine Caroline. August C.W. died at age two and it’s likely that Wilhelm M.F. died young as well. It’s unknown whether the second and third siblings – Johann and Johanne – stayed in Prussia.*

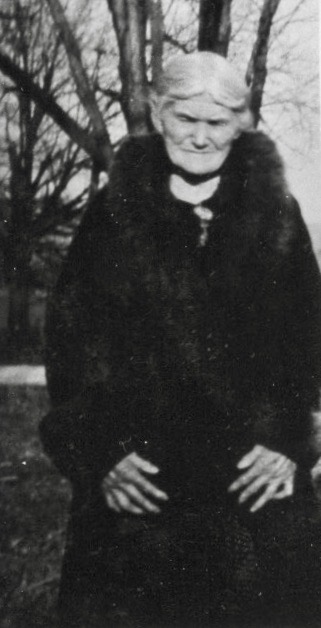

Both photos above are of Augusta Hahn Schmidt in the 1930s When I look at photos of my great-great grandma Augusta, I see pain as well as great strength. It’s hard for me to imagine everything she endured in her lifetime. In 1886, not long after arriving in the United States, Augusta’s mother Wilhelmine Caroline “Colleen” (Sahr) Hahn died at age 60. Grandma Colleen, as she became known in the U.S., had immigrated with her children after the death of her husband Johann. The next year, Augusta and Wilhelm’s daughter Anna died of croup before her third birthday. A decade later they lost their eldest daughter Millie from seizures caused by the measles. Millie was only 26 years old.

Augusta’s husband Wilhelm (William) Schmidt drank heavily and could be abusive towards Augusta and the children when intoxicated. He was arrested five times and convicted three times for such offenses. On one occasion in February of 1912, William attacked Augusta with a chair. Grandpa Frank’s brother Art feared for his mother’s life, tried to intervene but was threatened by his father with a revolver. Augusta decided she could endure this no longer. In July of 1912 she filed for divorce – a very rare thing for a woman to do at this time. The court sided with Augusta, awarding her custody of Frank and his brother John (the other children were legal adults by this time). Furthermore, the court granted Augusta sole ownership of the farm and created strict rules around when William could visit the property and use the horse for his masonry work.

According to my great-aunt Shirley, Grandma Augusta sold the farm and spent her later years living in a duplex in the Milwaukee area (not far from her son Art). She worked at a factory that made pots and pans, and in her spare time she knitted and sewed clothing for her grandkids. Aunt Shirley believes she had a “gentleman friend” in those years as well. I certainly hope she did.

[1] Augusta Hahn’s birth is recorded in the Hohenselchow-Woltersdorf church book for 1858 (Seite 87, Nr. 18), Blumberg Parish records at the Kirchenkreisarchiv Greifswald. These records were found thanks to the efforts of local historian and volunteer, Mr. Hartmut Wegner.

[2] Johann Hahn’s birth is recorded in the Hohenselchow-Woltersdorf church book for 1823 (Nr. 10), Blumberg Parish records at the Kirchenkreisarchiv Greifswald.

[3] Documentation of Wilhelmine Sahr and Johann Hahn’s marriage is found in the Hohenselchow-Woltersdorf church book for 1849 (Seite 152, Nr. 1), Blumberg Parish records at the Kirchenkreisarchiv Greifswald.

* All of the documentary evidence about the Hahns in Germany comes from the digital archives of Hartmut Wegner, the local historian in Mönkebude that I wrote about in yesterday’s post.

The Hahn family tree that Hartmut created for me on his computer based on church records that he found

Deep Roots

Reflections on family history, identity and geography

Home

Welcome! I’ve created this site to share family history and collective memories.