-

The Torblå farm

(This post is a continuation from yesterday’s post about Anders Andersen Torblaa and Anna Nilsdatter Skeie of Ulvik)

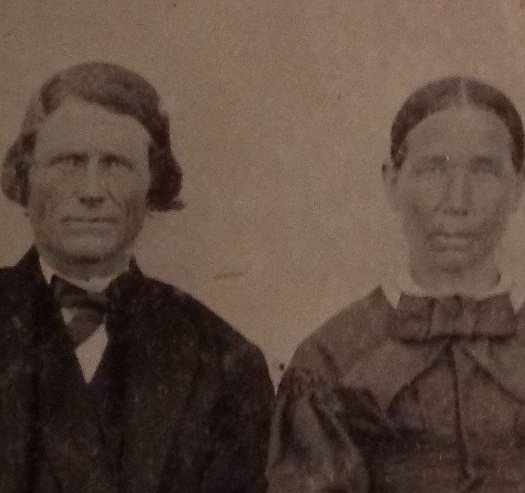

Anders Anderson Torblaa and Anna Nilsdatter Skeie, my 3x great-grandparents from Ulvik The Torblå farm (also spelled Torblao or Torblaa) is – like many Norwegian farms – actually a collection of several farmsteads rather than a single entity. The breaking up of farms into smaller and smaller parcels occurred throughout the 17th through 19th centuries, as Norway’s population grew and struggled to support itself on a limited supply of arable land. But the introduction of better health and sanitation measures (especially the smallpox vaccine in the early 19th century) led to a population spike that Norway could not support. Migration from farms to cities and emigration to the United States served as a release valve for this surplus population.

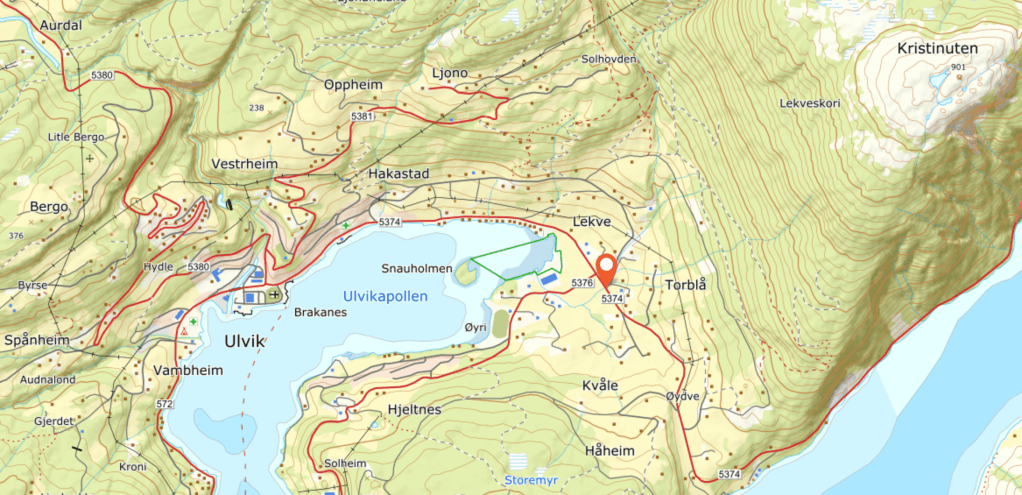

Our ancestor, Anders Andersen Torblaa (1826-1902), grew up on Bruk 12 of the group of farms called Nedre Torblå (Lower Torblå). Bruk 12 lies along the westernmost flank of the Torblå properties – the area closest to the town of Ulvik and the terminus of the Ulvikafjord. Anders was the son of Anders Olsen Osa (1785-?) and Guri Olsdatter Hetlenes (1802-1893).* As their “farm names” (farm-based last names) imply, neither of Anders’s parents grew up at Torblå, and as far as I can tell, the family’s connection to Torblå didn’t last more than a generation or two.[1]

Interestingly, when Anders and Anna immigrated to America, they are listed on the ship manifest as Anders A. Skeie and Anna Nilsdatter – he has taken his wife’s farm name here. In Wisconsin, they chose the farm name Torblaa as their last name but started spelling it Torbleau, which I think was a clever way to enforce a correct pronounciation as well as “Wisconsinize” the name. After all, so many Wisconsin placenames are French in origin. My AirBnB hostess informs me that the name Torblå comes from “Thor’s blót” — a place where “blót” (blood sacrifice) was given to the god Thor.

Ulvik, 1979: My grandma Phyllis Reiner Smith (middle) with a Torblå relative and her husband (left). At right are my grandma’s aunt Glenrose Johnson and Glenrose’s second cousin (on the Skeie side), Sigurd Undeland of Ulvik.

Location of Nedre Torblå, where our ancestor Anders Andersen Torblaa (Torbleau) grew up Yesterday I drove over to Nedre Torblå and met the current residents of the farm — Mr. and Mrs. Strømmen, who were out doing some gardening. The Strømmens are transplants from eastern Norway and they originally bought the place to be a summer home. But they liked it so much they’ve decided to retire here.

The Strømmens of Nedre Torblå I explained the family connection to the farm, and they immediately invited me into their home to show me some of the artifacts that had been left by the previous residents. Now, it’s unlikely that anything remains here from the time of our family — after all, they left in 1849. Still it was an extremely kind gesture and afforded me a fascinating glimpse backward in the life of a Norwegian farm.

Upstairs at Nedre Torblå Behind the house (which probably dates from the late 19th century) is an older outbuilding that was once used as a chicken coop. These days Mr. Strømmen has it decked out as a kind of luxury man cave (hvordan sier man «man cave» på norsk??), replete with comfy couches and a TV. But in a more rustic back room of that building he has a wall where he displays all sorts of odds and ends he’s found around the farm — tools, animal traps, farming equipment, etc.

The old chicken coop at Nedre Torblå

Terje Strømmen points to a trap that was probably used to catch foxes And in a second-hand shop in town, Mr. Strømmen found a painting (dated 1929) made by one of the farm’s former inhabitants, an artist by the name of Torgeir Lekve. Mr. Strømmen believes he’s found the remains of the old building shown in the painting.

Painting by Torgeir Lekve, dated June 8, 1929. The view here matches the view from Torblå. Before I left the Strømmens, they gave me two objects they had found in the house: a bowl and a prayer book. I was blown away by their generosity and kindness to a total stranger. Again, these objects are probably not old enough to be items my direct ancestors had used, but I’ll still cherish them, knowing they came from the Torblå farm.

The prayer book belonged to an Anna H. Lekve. The Strømmens haven’t had any luck finding her descendants. They thought I was close enough.

* I visited the Osa and Hetlenes farms as well — but only to stop and take photos. Osa is located a few kilometers from Ulvik on a separate inlet — the Osafjord. The area is stunningly beautiful and feels cut off from the rest of the world; the road simply ends in Osa.

The Osa farm, a secret corner of the world

The Hetlenes farm, located across the fjord from Ulvik [1] Kolltveit, Kvestad and Dyrvik. (1987) Ulvik: Gards- og Ættesoga Vol. 1, p. 481.

-

Trading fjords for prairies: the Torblå-Skeie family of Ulvik

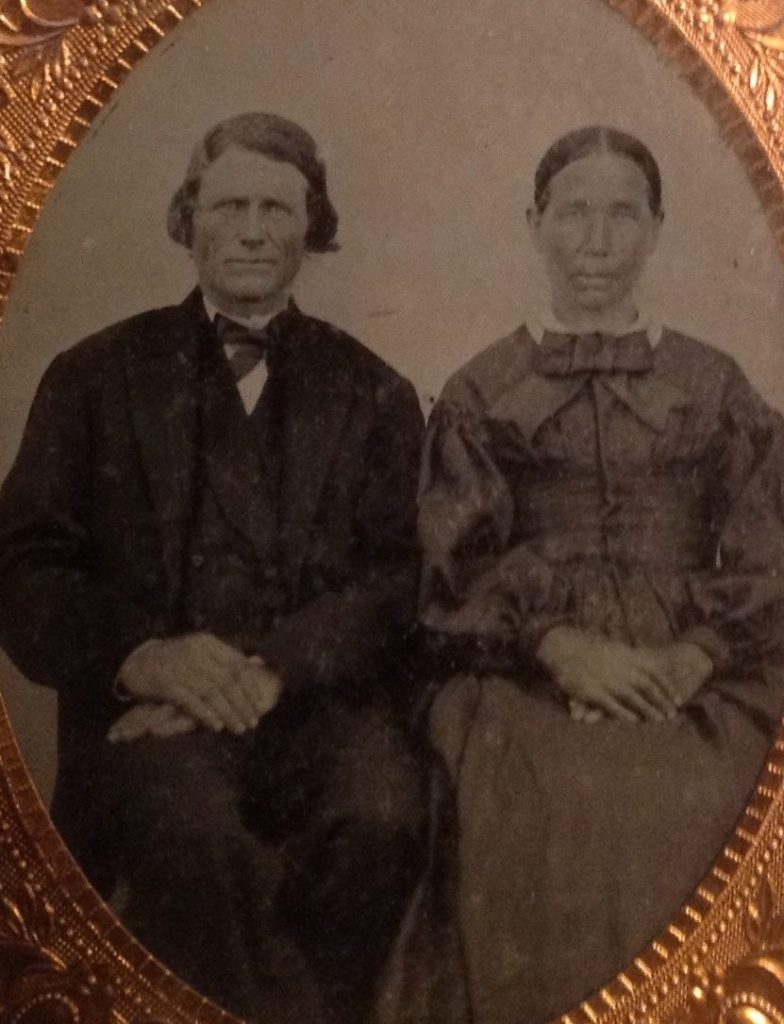

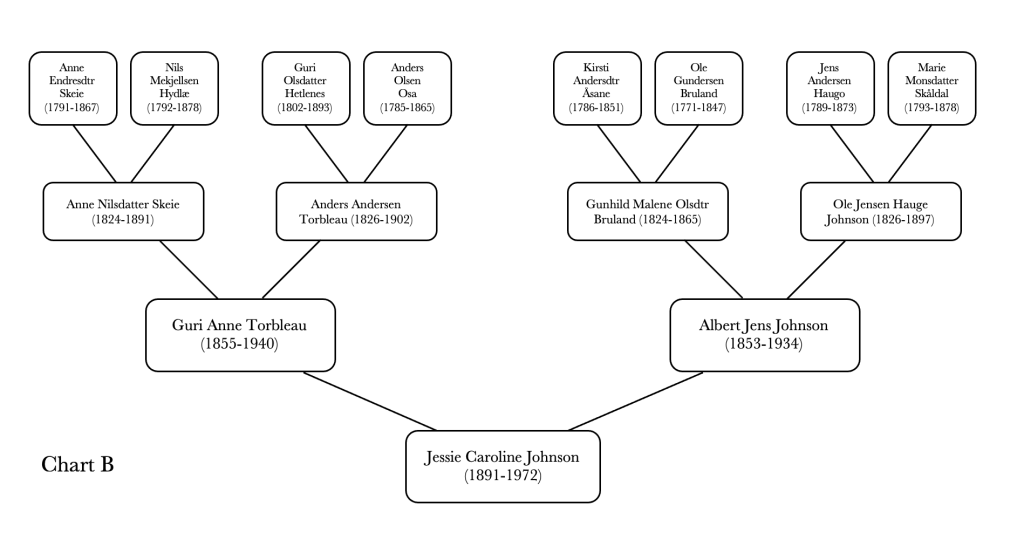

My great-grandma Jessie Johnson Reiner’s mother was Julia Torbleau Johnson (1855-1940). Like her husband Albert Jens Johnson (1853-1934), Julia was born soon after her parents arrived in Wisconsin from Norway.

Albert Jens Johnson and Julia (Guri) Torbleau Johnson (parents of my great-grandma Jessie Johnson Reiner) Julia (who was called Guri in Norwegian) was the third of seven children born to Anna Nilsdatter Skeie (1824-1891) and Anders Andersen Torblaa (1826-1902). It’s their story that I’m exploring today.

Anders Andersen Torblaa and Anna Nilsdatter Skeie: parents of Julia Torbleau Johnson (Julia was the mother of my great-grandma Jessie Johnson Reiner) Anna and Anders met, married and had their first child, Anna, in Ulvik – a picturesque community tucked within an inlet of the Hardangerfjord.

The town of Ulvik, which sits on the Ulvikafjord — a finger of Hardangerfjord (Norway’s second largest fjord) In 1849, about a year after marrying, they decided to trade fjords for prairies. On June 9th of that year, they took an arduous two-month voyage from Bergen to New York aboard a ship called the Juno, and afterwards made the long trek to Wisconsin.*

Thanks to the research of prior generations and relatives’ trips to Norway, we’re fortunate to have a wealth of information on Anna and Anders’ origins in Ulvik.

Location of Ulvik (far right) relative to Bergen (far left) The Skeie farm (sometimes also spelled Skjeie) is where Anna’s family lived and worked. It was located on the west side of town, just a couple hundred meters from the Ulvik Church.

Skeie is no longer a farm but a group of houses with some large gardens; and much of the old farm is now the grounds of the Brakenes School. Anna’s father Nils Mikkelsen (1792-1878) grew up on a section of the Hydlæ farm, but in 1821 he inherited Bruk 2 of the Skeie farm from his father-in-law, Endre Aslaksen (1763-?)[1]. Bruk 2 was the childhood home of Anna’s mother, Anna Endresdatter (1791-1867). [Note a “bruk” is a subdivision of a larger farm. Due to population increases and resulting land shortages, most large farms in Norway were broken up into smaller farmsteads in the 17th-19th centuries.]

By chance, the AirBnB where I’m staying is an old farmhouse on the Hydle property — quite possibly the location of the childhood home of my 4x great-grandfather Nils Mikkelsen.

My home for the next two days — the Hydle farm in Ulvik Another amazing coincidence: my AirBnB hostess, Berit, and I discovered that we are 4th cousins once removed. Her great-great grandpa Endre Nilsen Skeie and my great-great-great grandma Anna Nildatter Skeie were siblings.

Berit and I on the back deck of her home. Berit is a descendant of Anna Nilsdatter’s brother Endre Skeie.

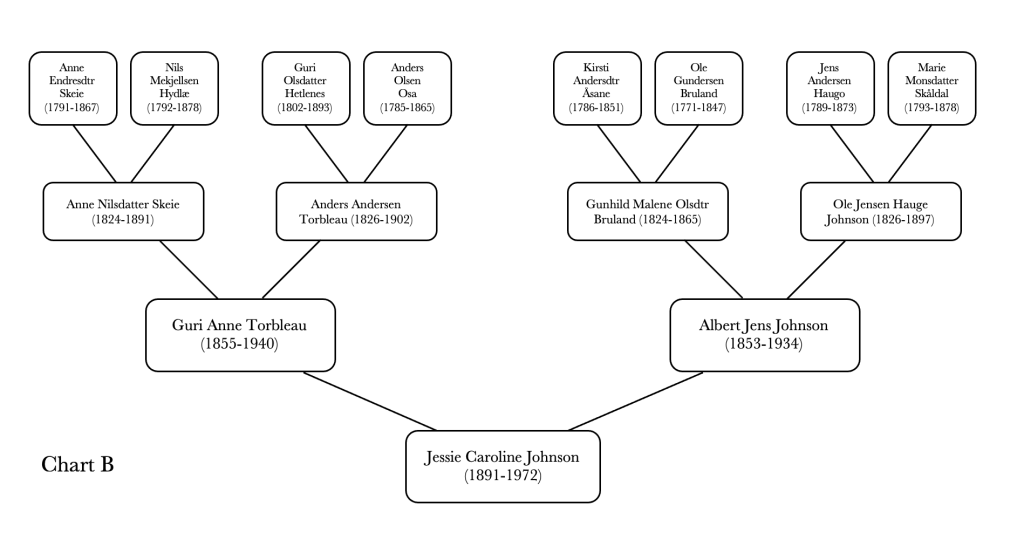

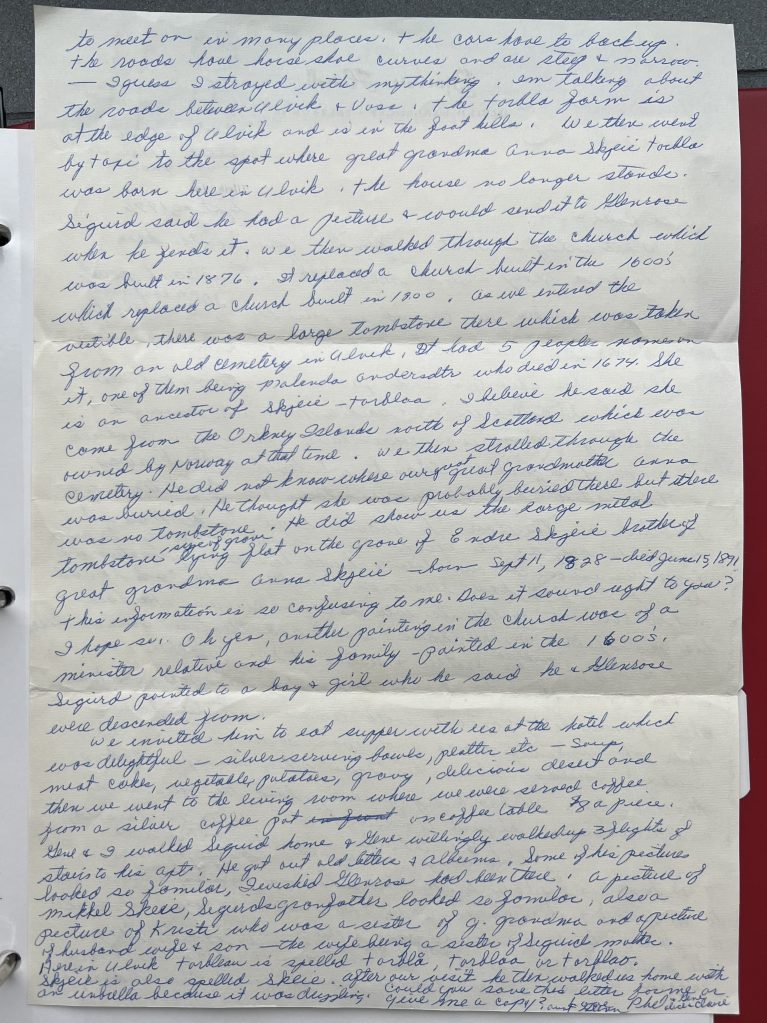

Direct ancestors of Jessie Johnson Reiner (my great-grandmother) Five of our family members visited Ulvik in 1979: Phyllis Reiner Smith and Eugene Smith (my maternal grandparents), Phyllis’s sister Alice Reiner Quam and her husband Claire Quam, and Phyllis and Alice’s Aunt Glenrose. While in Ulvik, the group met a man named Sigurd Undeland who was not only a relative (a second cousin to great-grandma Jessie and Aunt Glenrose) but also a local history buff and artist.

Letter to Helen & Bob from Phyllis (in Ulvik) In the letter my grandma wrote to her sister and brother-in-law, Helen and Bob Reed, she describes her stroke of good fortune in meeting Sigurd (then 76 years old) and how he took the group to meet other relatives and visit the Ulvik Church. In the Ulvik Church, they got to see the family portrait of Tomas Samuelsen Uro (1606-1687) and Anna Rasmusdatter (1617-1696) – my 9x great-grandparents. Uro was from Copenhagen and served as the minister in Ulvik in those years. Our family is descended from Uro’s son Daniel, who appears directly under Uro’s hands in the portrait.

Family portrait of Tomas Samuelsen Uro and Anna Rasmusdatter, which hangs in the Ulvik Church (I arranged to meet the verger of the Ulvik Church — a delightful woman named Wilma van Manen who has lived in Ulvik for many years. Wilma gave me a thorough tour of the church and provided details about its colorful history. To learn more about my visit to the Ulvik Church, see this post.)

Sigurd said that his mother had expressed remorse about losing contact with our branch of the family. I wish Sigurd were still around; he died in the 1980s. I’d love to tell him that our branch of the family still feels a connection to Ulvik, despite having left 173 years ago. I’ve been hearing about Ulvik all my life and can’t believe it has taken me 47 years to get here.

* Fascinating details of this taxing journey to New York can be found on this website: http://www.norwayheritage.com/p_ship.asp?sh=junoa

According to a letter written by one of Anders and Anna’s fellow passengers, the Juno was delayed leaving Bergen by three weeks due to unfavorable winds. Two days after setting sail, the ship hit rough seas when passing Great Britain, making most of passengers seasick. The writer of the letter traveled to Wisconsin by means of a series of ships from New York to Milwaukee which traversed the Hudson River, the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes. It seems likely that Anders and Anna would have taken the same route since Wisconsin was not yet linked by rail. In total, the journey from Ulvik to their final destination in Dane County, Wisconsin may have taken them around four months. This puts some of our modern “travel nightmares” into perspective!

[1] Kolltveit, Kvestad and Dyrvik. (1987) Ulvik: Gards- og Ættesoga Vol. 2, p. 351.

-

A visit to Ulvik kyrkje

I came to Ulvik to try to imagine how my ancestors might have worked, prayed, lived and died. And the town does not disappoint in this regard. There is clearly a certain reverence for the past here, and many old houses and farm buildings have been lovingly preserved and restored. And yet, Ulvik is not an open-air museum. It’s a normal (albeit especially beautiful) small town with modern people living modern lives.

Ulvik’s church is a living, breathing example of how past and present can’t be fully separated — despite our best attempts (see this post on that subject). The “new” church is an 1859 reconstruction of the “old” church, which was built in 1711. But before this there was a stave church in Ulvik that dated back to at least the 1290s.

Ulvik kyrkje My direct ancestors, having left Ulvik in 1849, never attended this “new” church. But there are elements of their church that they would recognize, as many artifacts of the older churches have found their way into the present structure.

Wilma van Manen, the church verger, took me on a guided tour of this magnificent building, and explained how those various pieces come together.

Wilma van Manen, verger of Ulvik kyrkje. Behind her you can see the ornately carved arch leading to the altar and the richly painted walls.

This bell rang in Ulvik’s tower from the 1300s until it finally broke a few years ago. Behind the bell you can see one of the stoves that was in use to heat the building until the 1950s when a more modern (less risky) form of heating was introduced. Wilma is currently in the process of updating that system.

All babies born in Ulvik since the 1300s to the present day have been baptized at this font.

A painting of my ancestors — the Uro family, who lived in the 17th century. Note the three children dressed in white above the skull; these are the siblings who did not survive.

This is one of the older altarpieces that hangs towards the entrance of the church. It dates from the 1630s and would have been in use when my ancestor Tomas Samuelsen Uro was the parish priest at Ulvik.

The carved arch

A model ship, donated by a parishioner who immigrated to the US in the 19th century, hangs above the nave. The string that it hangs by was pierced by Nazi bullet fire during WWII, causing the ship to fall. But it survived, and so did Ulvik.

This is a copy of Ulvik’s medieval altarfront. The original dates to 1250 and hangs in the Bergen Historical Museum. Amongst all of this history, I noticed that a couple of pews had been removed to create a children’s play area — a place for children to be children yet still be included in the church service. This served as a reminder to me that this is a functioning church; a church that is thinking about its future as well as its past.

-

Reflections on the preservation of memory

The colonization of North America is so relatively recent that our notions of what’s “old” and “worth preserving” are a little different from those of our European counterparts. Similarly, a fascination with family history, while not unique to Americans, takes on an oddly obsessive quality among some in the U.S. (ahem…. guilty as charged).

Any time we attempt to reconstruct the past, there is a tendency to gloss over certain details and emphasize others — often through the lens of present-day values and systems of power. There’s also an urge to present “facts” when what we really have are hunches. Does our relatively short collective memory in (non-Indigenous) America make us more vulnerable to these distortions? I wonder. (If you have thoughts on the subject, please post a comment below!)

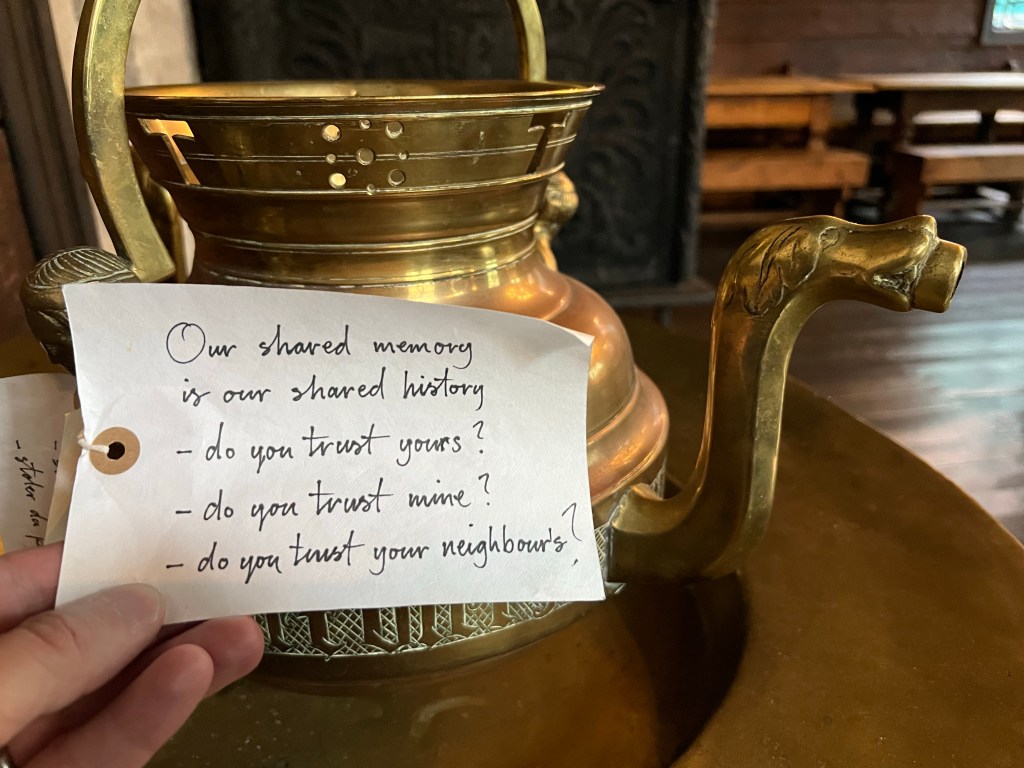

I started my day yesterday in Bergen, where I visited the Hanseatic Museum’s “Schøtstuene” (assembly rooms used by the German Hanseatic merchants who had established themselves in Bergen by the 1240s). One thing that I loved about the exhibit was how the curators presented ambiguities in the historical record. The exhibit took great pains to distinguish originals from copies from reconstructions (and all flavors in between). But they often admitted that they didn’t know. And the curators posed as many questions as they provided answers.

Bredsgårdens schøtstue: one of the “original” meeting rooms of the Hanseatic merchants, although it has been rebuilt, taken apart, stored, moved, and reassembled in its 313 year history.

Some brilliant self-reflection right here

Now they’re just messing with me This playing with the admixture of originals and reconstructions is taken to a whole other level at the Gamle Bergen Museum — a collection of old homes and businesses from all over Bergen that have been reassembled into an open-air museum. Actors in 19th century dress sit patiently in opulent sitting rooms, waiting for you to arrive so that they can recount the day’s events. As a former resident of Williamsburg, Virginia, where I was sometimes chatted up by 17th century “re-enactors”, you’d think I’d be prepared for this sort of thing, but I never am.

The Merchant’s House at the Gamle Bergen Museum. (If you think historical interpretation is tough, imagine having to live it multiple times a day!)

This smooth-talking salesman tried to sell me some 100 year-old canned fish balls. I opted for the overpriced chocolate bar.

Gamle Bergen — a reconstruction of a town that never was, which gives a real sense of how it might have been.

Thanks for permitting a little historical navel-gazing… now back to our regularly scheduled programming -

Norway’s Wild West – the origins of the Johnson-Hauge family

When you fly into Bergen, you are treated to glimpses through the clouds of an almost surreal landscape. Mountains rise straight up from the fjords with brightly colored buildings perched at intervals. Here and there a waterfall gushes down the steep slopes.

View of the Bergen suburbs from the plane

Downtown Bergen One branch of my mom’s family, the branch we call “the Johnsons”, hails from this wild western terrain. The Johnsons are the family of my mother’s maternal grandma, Jessie Johnson Reiner (1891-1972) – specifically, Grandma Jessie’s paternal grandparents, Ole Jensen Hauge (1826-1897) and Gunhild Malene Olsdatter Bruland (1824-1865). I never knew my great-grandma Jessie, as she died three years before I was born, but I inherited her name as well as her love of language and family history.

Jessie Johnson Reiner, my mother’s mother’s mother

Direct ancestors of Jessie Johnson Reiner (Confused where this fits in? See this page.) Ole and Malene reportedly changed their last name from Hauge to Johnson because there was a justice of the peace in the area who went by Ole Hauge. Besides, the Yankees kept mispronouncing it as “hog”. Johnson was probably an Anglicization of Ole’s patronymic name, Jensen. Malene also Anglicized her first name as “Malinda” after immigrating.

Much of our information on the Johnsons’ immigration and early years in America is apocryphal at best. In 1971, a first cousin of my great-grandma Jessie, Beulah Kringel Bell (1881-1975), relayed the Johnsons’ story like this:

It was the custom in those days for the daughters of the family to go to work for a neighbor, a sort of daughter exchange arrangement helpful in their education. Unfortunately, Malene had a hard task mistress and was quite unhappy.

However, after a time, she met a young man named Ole Hauge. They soon fell in love and became engaged. Malene was a lovely and charming young lady. She had deep blue eyes. Her blond hair was parted in the middle and hung in long curls around her neck, as was the custom in those days. Ole was a strong, handsome young man with bright blue eyes. He had a hearty laugh and was a good singer. He was a stonemason by occupation. They decided they wanted to go to America which then, as now, was the popular thing to do. They made plans to save as much as possible of their small wages so they could have a fine wedding and make the trip to America. One day Malene had the bad luck to break a cup, a beautiful and valuable porcelain china cup. Knowing or at least fearing she would have to pay for it out of her precious savings, she brokenheartedly told Ole. He was also deeply concerned. They did some hard thinking and finally decided to elope and go immediately to America.

(These passages were excerpted from the Johnson family history written in the early 1970s by my great-grandma’s sister, Glenrose Johnson).A fascinating tale… but is it true? Unfortunately, we’ll never know. What we do know is that Ole and Malene arrived into New York harbor on July 11, 1850 aboard the brig Nordlyset from Bergen. According to the family history written by my great-grandma Jessie’s sister Glenrose, they married “in the Methodist parsonage” in Cambridge, Wisconsin on March 10, 1851. But my great-aunt Helen’s records list a “legal” marriage taking place on August 11, 1850 – exactly one month after their immigration.

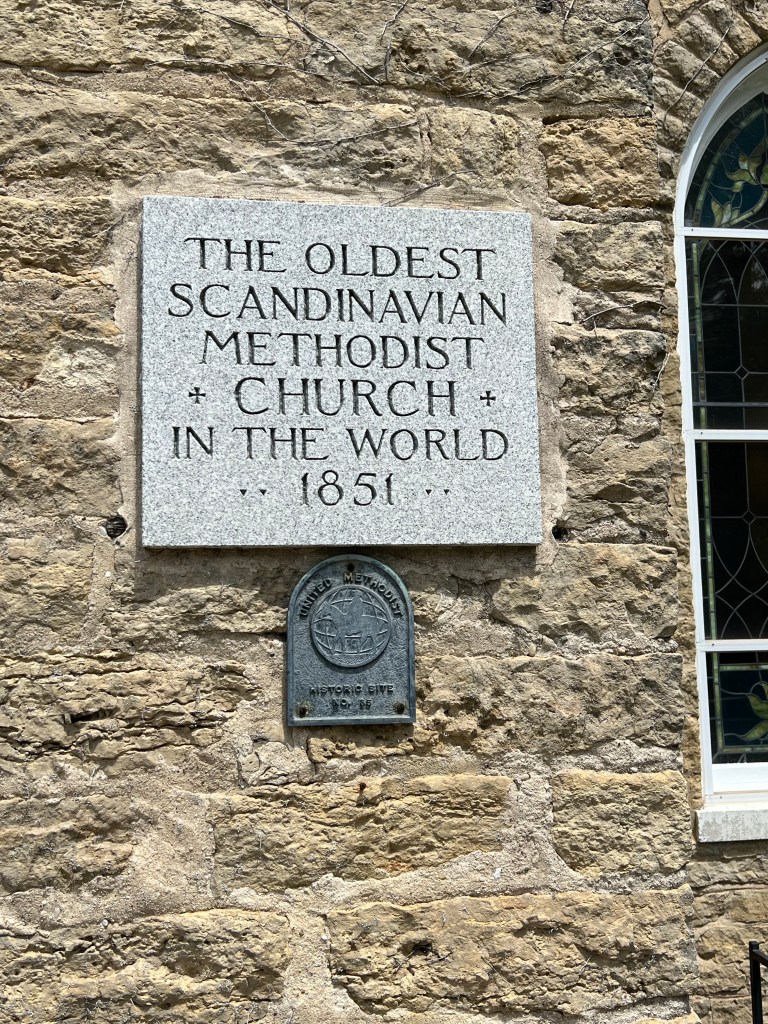

Cambridge’s Methodist congregation was founded by the Danish minister Christian Willerup around the same time as Ole and Malene were establishing themselves in town. In the early 1850s, Ole put his masonry skills to use in helping build the congregation’s church building on Water Street. Today Willerup Methodist Church holds claim as the oldest Scandinavian Methodist congregation in the world. Aunt Glenrose wrote that Ole was a deacon and Malene was a Sunday school teacher in the church (I haven’t found evidence in the Willerup church archives to support these claims, but I did find my great-great grandfather Albert Johnson’s baptism).*

Searching the archives at Willerup Methodist in Cambridge, WI (June 2022)

Ole Jensen Hauge Johnson — father of Albert Jens Johnson (Albert Johnson was the father of Jessie Johnson Reiner) Until recently, Ole and Malene’s origins in Norway were a mystery. Aunt Glenrose wrote that Ole was from Bergen and Malene was from “South Fjord”. Thanks to the work of other family researchers online, Malene’s roots were traced to a town called Førde, located in a region of Sogn og Fjordane called Sunnfjord (which does translate to South Fjord). I’m not visiting Førde on this trip because it’s a good deal out of my way.

But I did have the good fortune to visit Ole’s hometown today.[See correction below.]Earlier this spring, through a series of happy accidents and (if I may say so) clever sleuthing, I finally discovered Ole Jensen Hauge’s family of origin. To anyone uninterested in family history, it’s hard to convey the excitement of unlocking a mystery that has been out of reach for decades. My mom’s Aunt Helen had made inquiries in the 1980s, and she and I had all but given up on ever solving this puzzle.

Ole Jensen was born on September 15, 1826 to Marie Monsdatter and Jens Andersen of the Hauge farm within the Haus Clerical District

in Osterøy, Hordaland. Osterøy is technically an island, as it’s surrounded by fjords on all sides, but the Hauge farm is an easy 40-minute drive from Bergen today via the Osterøy Bridge.[CORRECTION MADE ON FEB 19, 2025: I was mistaken when I thought I had located the Hauge farm in Haus. Well, I had found a Hauge farm in Haus, but not the correct Hauge farm in Haus! Back in the 1800s, the Haus Clerical District was composed of three parishes: Haus, Gjerstad, and Ådna. Our family lived on the Hauge farm in Ådna parish (near the community of Indre Arna within what is now Bergen) — not the Hauge farm in Haus parish. I hope to return to Norway one day and locate the correct farm.]While Ole and Malene’s hometowns are only about a 3-hour drive from each other using today’s technology, they were worlds apart in the 1840s when the two were courting. I wonder how they might have met. Did Ole travel north in his 20s looking for work? This is one mystery that may remain unsolved.

* Given the Johnsons’ connection to this church’s founding, we might speculate whether their immigration was religiously as well as economically motivated. After all, dissenters from the Lutheran state church in Norway had been prominent emigrants since the sloop Restauration set sail from Stavanger in 1825. But unlike Quakers or Haugean Lutherans, the first Norwegian Methodists were actually American converts like Ole and Malene. Willerup himself left Wisconsin in 1856 to found some of the first Methodist churches in Norway.

Willerup Methodist Church in Cambridge, Wisconsin -

A sense of place

I’m in Southern Wisconsin for a few days, wandering around some of the towns and farms where ancestors of mine have dwelt for 170 years. I haven’t lived here since I was five, but deep down in the fibers of my being, this place has always felt like home.

And of course it isn’t my home. I don’t have friends here, I don’t know what’s going on locally, and I’m a stranger to those who pass me in the street. But all four of my grandparents grew up within the same 20 square miles (as did six of eight great-grandparents*), and I have almost a half century of my own memories of visiting family here.

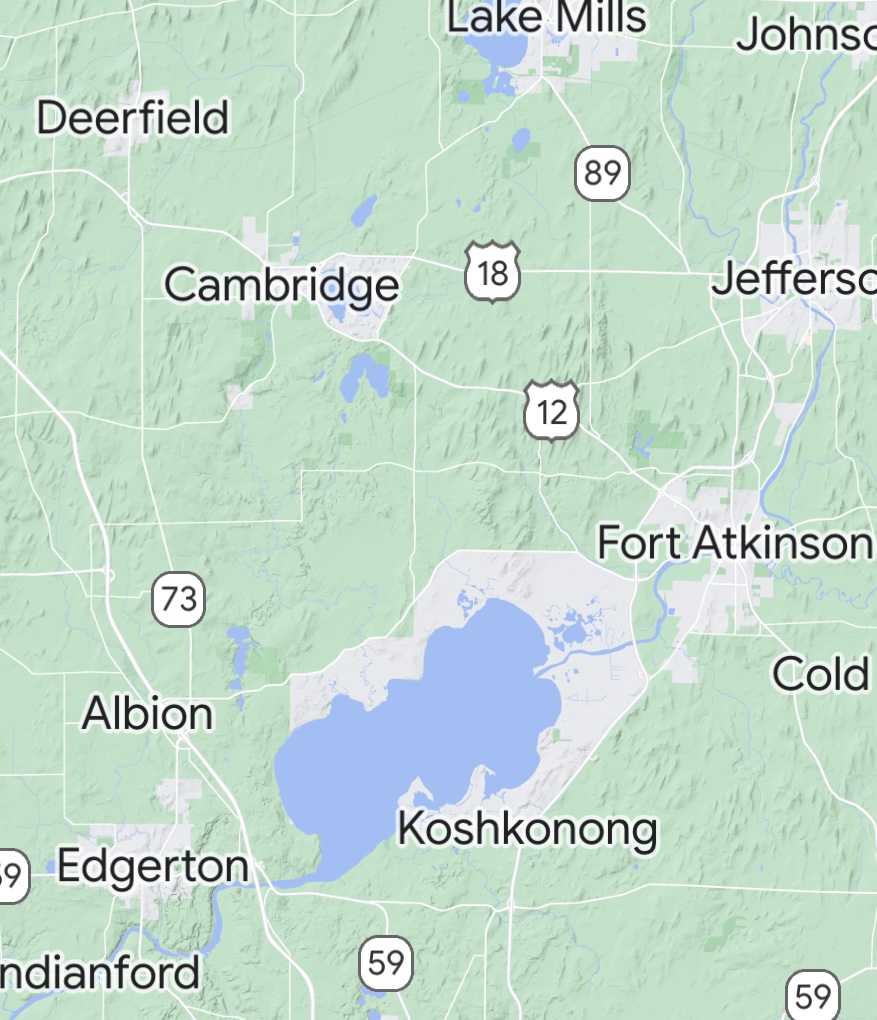

Where Dane, Rock and Jefferson counties meet My life has been a series of moves — both in childhood (Edgerton, WI to Syracuse, IN to Lexington, VA) and in adulthood (Williamsburg, VA to Japan to San Francisco to Minneapolis to Los Angeles to Chicago to New York, and back to Minneapolis). What has kept me grounded, in all of this, is a strong sense of where I’m from. I can point to these 20 square miles in rural Wisconsin and say, “That’s home” (and mean it). Do I want to live here? I’m sure I would love living here. It’s fun to be near family and these rolling hills are beautiful, but I suppose I’m content with being an occasional visitor. I am grateful this place exists and that I can come here and reconnect with my roots.

Smith-Reiner Drumlin Prairie State Natural Area

Spence and I on the prairie that was once owned by my grandparents and great-grandparents * All eight of my great-grandparents grew up in Southern Wisconsin but two of the six grew up just outside of the little box I’ve drawn on the map.

-

The greats

During my formative years (i.e., the early 1980s), I recall a flurry of genealogical interest on multiple sides of the family. My paternal grandpa’s sister Carol (Rude) Luiso had been interviewing her father John Rude and other older relatives about the family’s early years in the US. She and her cousin Judi collected a wealth of information about both the Helgestads, my grandpa’s mother’s family, as well as the Rudes, my grandpa’s father’s family.

Meanwhile, my maternal grandmother’s sister Helen (Reiner) Reed was in the midst of writing her book about her father’s paternal grandparents — Elsbeth (Hitz) and Johann Jacob Reiner, who had immigrated from Switzerland and Württemberg to Madison, Wisconsin in the late 1840s. It was around that same time that my maternal grandparents welcomed relatives from Norway — just a couple years after they themselves had traveled to Norway to see the villages of their forebears and connect with distant family. This was also the time that my maternal grandpa’s sister Shirley (Smith) Stork was busy compiling her many binders of information about her father’s family from Pomerania (Prussia) and her mother’s family from Norway.

Is it any wonder then that something was sparked in me? With all the family history talk happening around the kitchen table, these “ancestors” started to feel much closer, much more real. They weren’t just people with funny-sounding names who had lived and died a long time ago. I started to see a connection between their lives and mine. And for this, I have my great aunts to thank — especially Carol, Helen, and Shirley. They are they greats on whose shoulders I stand.

Of course, these ladies can also thank the previous generation for carefully preserving family history. There are another set of greats. I’m thinking especially of the mother of Aunt Shirley and my grandpa Gene Smith — my great-grandma Elvina Anderson Smith. My great-grandma Jessie Johnson Reiner was also keenly interested in family history. She and her sister Glenrose passed along countless stories from their parents and grandparents. All of us who carry the torch of family history are indebted to these greats as well.

Fredericksburg, Virginia: My great-grandmother Jessie Johnson Reiner (right) visiting her Aunt Lena Torbleau Savee (left, aged 103) -

An early memory

When I was four or five, I asked my mom about her “mommy and daddy”. She explained that this is who “grandma” and “grandpa” were. Then I asked her about grandma and grandpa’s mommy and daddy. She patiently explained that too. And their parents, and their parents’ parents…? Where did it end? I wanted to know. I still remember a befuddled look and a mumbled response from my mom about how God started it all. That answer didn’t quite satisfy me. “What about God’s parents?” I’d asked. Well, now I had her stumped.

Tracing our roots back, even just a handful of generations, has the capacity to elicit feelings of wonder and awe. The mathematics alone are staggering: two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents… and on it goes, doubling each time. Going back 10 generations from ourselves, we meet our great (x8) grandparents, and there’s 1,024 of them. If we go back 10 more generations, we meet our great (x18) grandparents, and their number has reached a whopping 1,048,576. Because people routinely marry their distant relatives, no one has a perfect doubling each generation — something genealogists call “pedigree collapse”. But still, it’s mind-blowing to consider how few generations one needs to go back to connect to vast populations on the planet. Of course, ultimately, every living creature on the planet is a distant cousin, as we all descended from the same primordial goo. And if that’s not humbling, I don’t know what is.

My mom and me around 1979 or 1980 (home on York Rd in Edgerton, WI)

Deep Roots

Reflections on family history, identity and geography

Home

Welcome! I’ve created this site to share family history and collective memories.